Painting means observing the world, breathing in all of its forms and colors and transforming that infinite variety into the most concentrated forms of thought. This is the real meaning of abstraction and not sprinkling just any shapes and colors in bulk on a surface.

“Painting is a mental activity” (Leonardo da Vinci)

Every description we formulate of the world is a process of transposing the infinite physical reality into finite mental constructs that we can use to observe, examine, and establish relations between different phenomena and things around us. Physical reality is to be understood both as the macrocosm outside us and as the microcosm within us.

It must, however, be remembered that these constructs are abstractions of the real phenomena, which are of a far more complex and almost infinite nature than the ideas we make of them.

Every era and every civilization or culture has its own ideas about reality. While we do our utmost to give precise shape to our ideas, reality slowly changes and we therefore should be able to change our ideas about it. While this is obvious in scientific activities, it is not at all so when dealing with social, moral or religious issues.

We have been aware ever since Immanuel Kant that we can know our representations of phenomena but not phenomena in themselves. Nevertheless, we identify our mental symbols with physical phenomena out of habit and we take our ideas as true reality for the sake of convenience.

Every work of art is the creation of a finite field of relations that seek to evoke the far more complex and elusive relations perceived in the space of real life.

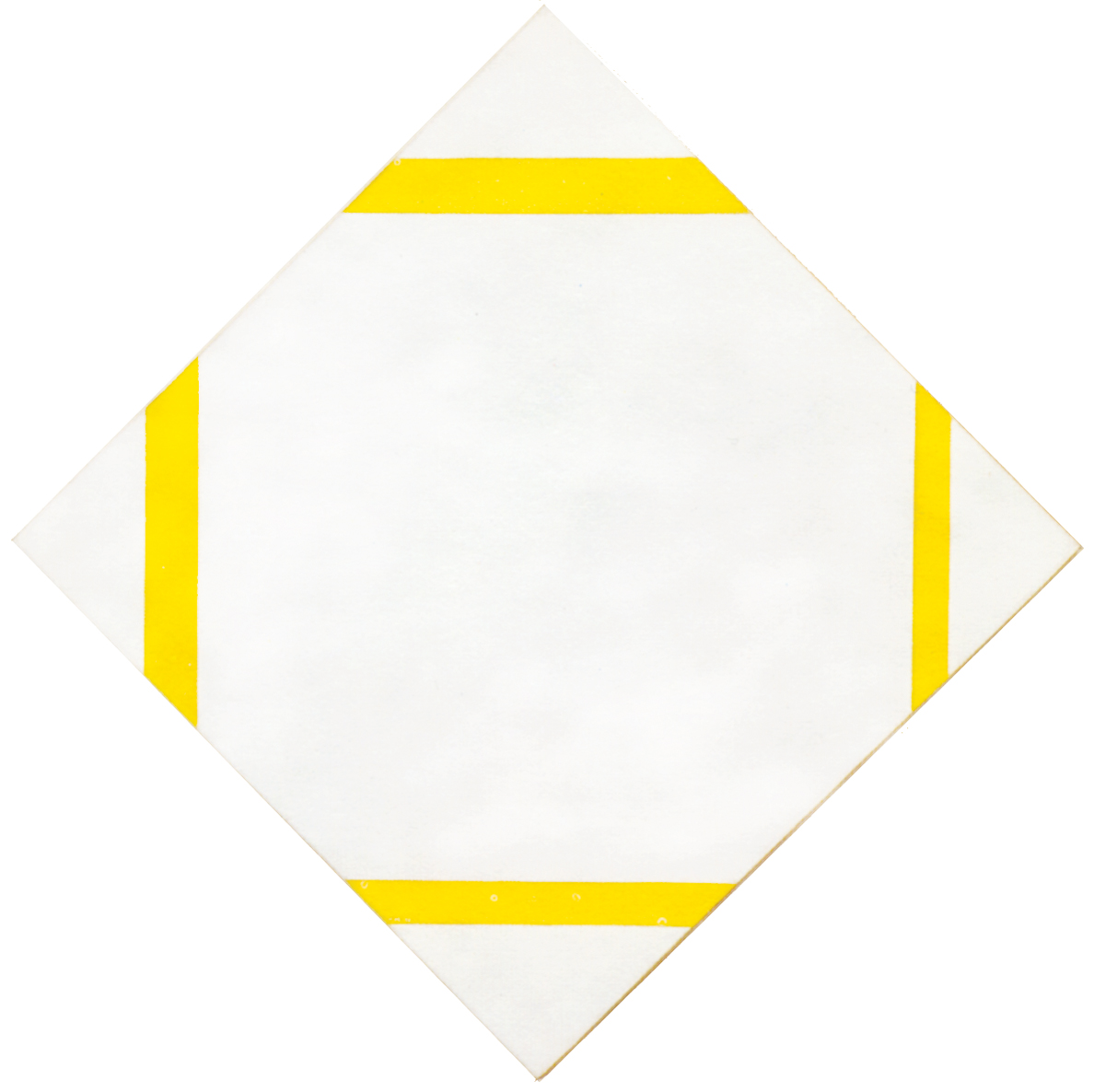

Abstracting a common basic structure from the fleeting aspect of single things enables the Dutch painter to represent the broadest range of variation without getting lost in the outward appearances of countless things that fragment the consciousness and prevent an overall vision.

As Mondrian put it, “Art should express the universal.”

Harassed as we are by the frenzied pace of life, we have lost the capacity to consider questions of greater breadth. We have reached the point of being ashamed to talk about universal issues.

These pages are also dedicated to those who truly believe that abstraction can be reduced to a superficial exploration of cold geometry for its own sake. This has, unfortunately, been the case with many, all head and no heart, the type Fausto Melotti referred to as “hardworking clerks of abstraction”.

A realistic or, if you prefer, a figurative artist, Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, said:

“It is not real truth that I must represent in the painting but ideal truth. The conflict of these two forms of truth in the mind of the artist who produces the work ensures that it will remain incomplete. Artists who stick too close to reality in their pursuit of truth fail to achieve their objective. It is through the sacrifice of real truth that ideal truth is attained.” .

back to reflections

Copyright 1989 – 2025 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More