The entire evolutionary process of Piet Mondrian’s oeuvre and its substantial meanings can be explained by examining three key works:

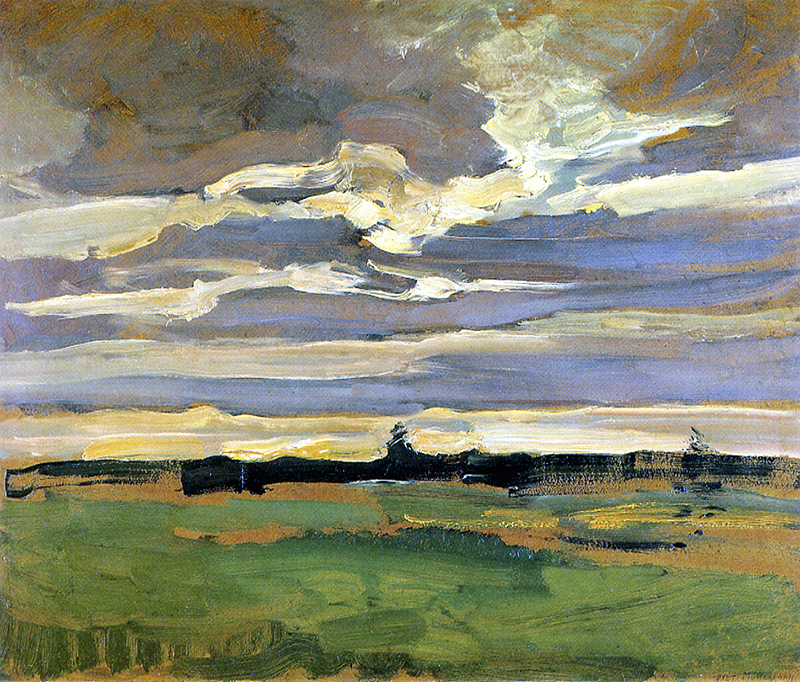

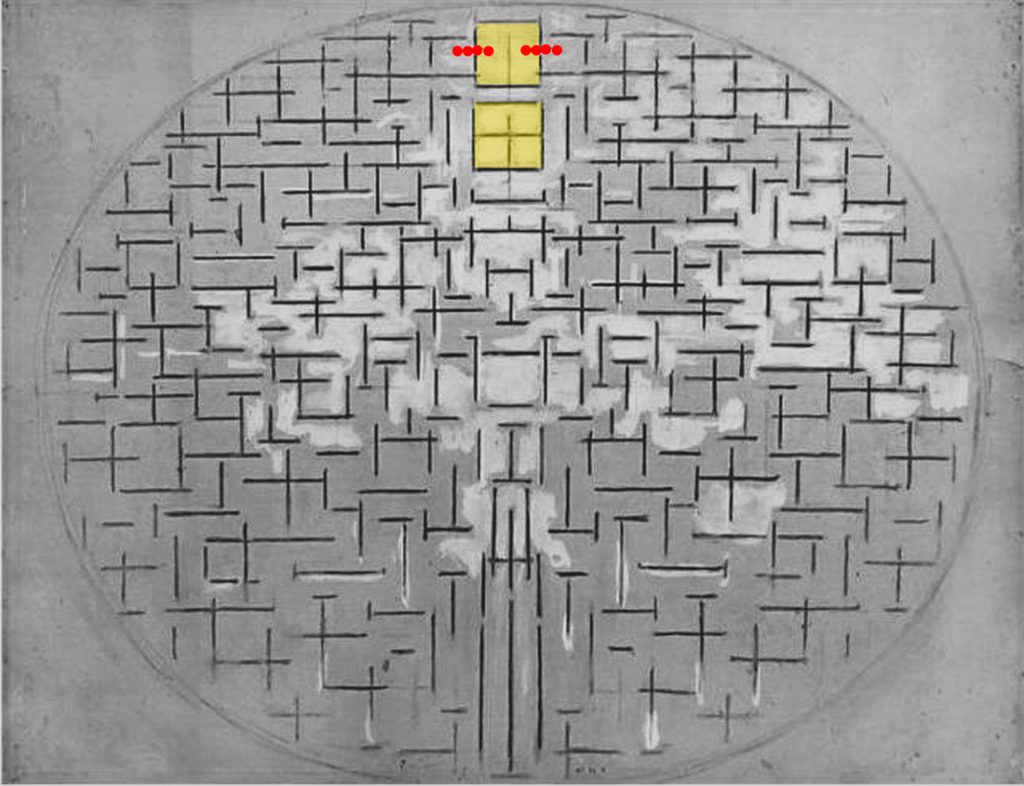

1908-10

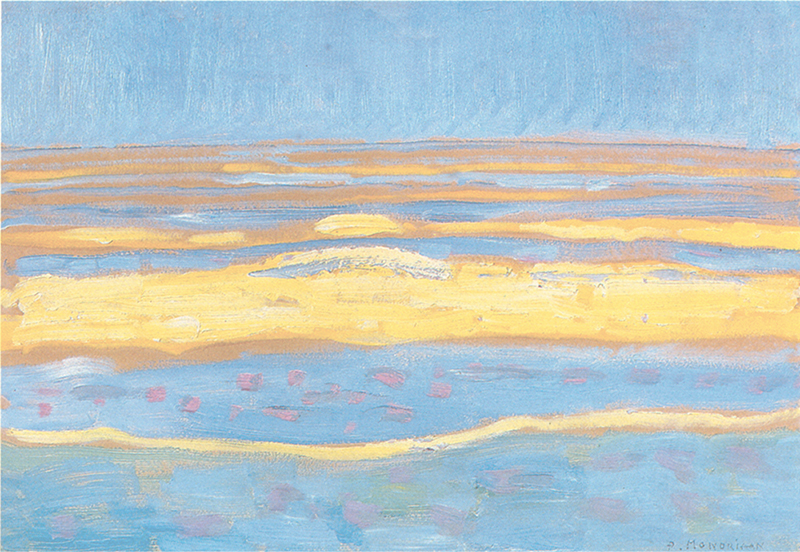

1915

1942-43

We shall examine these three works to show how from 1908 to 1943 the artist sought the most suitable way to express in abstract, i.e., universal terms the same basic idea of a dynamic interaction between multiplicity and unity, that is to say, between the endless variety and mutability of the world around us and within ourselves on the one hand and the need to contemplate the intrinsic unity of all things on the other.

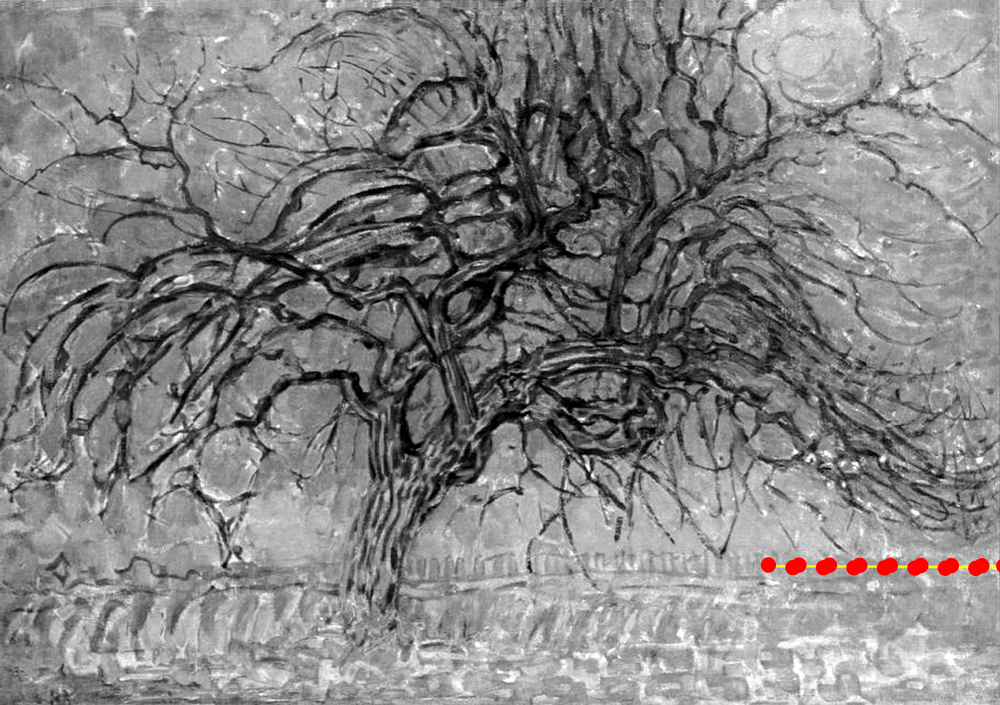

The Red Tree

In the figure of a bare tree we see the horizontal extension of the ground presenting a sequence of small vertical strokes that consolidate to form the trunk, from which a multiplicity of branches project before pointing again toward the ground on the right.

The same process can be observed in:

Apple Tree in Blue

Final Study for The Red Tree (Evening)

The horizontal line of the ground continues to the right and to the left suggesting the boundless extension of nature which was emphasized in the landscapes of the same years through a dominant horizontal space:

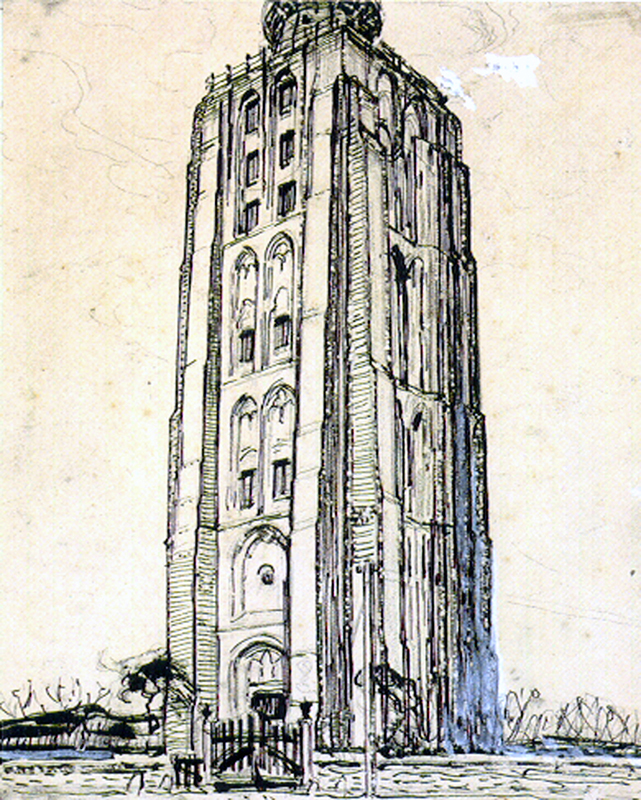

The tree trunk, instead, is vertical like the architectural volumes of mills, lighthouses and church towers of the same period:

The artist ascribed to the horizontal the value of everything that can be defined as the “Natural” not only in the sense of the natural landscape but also as anything that before our eyes and within ourselves in the course of our lives constantly changes. In the vertical, instead, the artist saw a symbol of the “Spiritual” that is, of the human quest for constancy, stability, unity.

Mondrian was a great painter capable of transforming the surface of the canvas into a precious artifact as regards richness of texture, combinations of color, and dynamic balancing of the composition. It is essential to see the original works in order to appreciate all their beauty. His aim in painting those landscapes, lighthouses and trees was not, however, solely to reproduce the fleeting appearance of things. The artist read and interpreted those objects as plastic symbols of a deeper reality, as visual metaphors of existential meanings. At this stage Mondrian’s eye addressed the objects and situations of the external world but pulsated with a wholly internal rhythm.

The Red Tree: Through the unifying action of the vertical trunk, the horizontal, virtually infinite extension of the ground is condensed into a finite space (the set of branches) which manifests an unpredictable multiplicity (the Natural) while maintaining a synthetical wholeness (the unity invoked by the Spiritual) that is entirely encompassed within the painting.

It is worth pointing out that the canvas is for the artist a reflection of consciousness.

The ground line, instead, suggests a whole extending beyond the canvas as the coeval landscapes that disrupt our field of vision boundlessly to the right and to the left.

In this perspective, the set of branches appears as a symbol of the synthesis attempted by consciousness while dealing with the infinite and manifold space of nature, that is, the elusive space suggested here by the virtually unlimited ground line.

The interaction between the horizontal of the ground (the elusive space of nature) and the vertical of the trunk (the concentrating action implemented by thought) generates a manifold whole (the set of branches) which is, as mentioned, fully included within the canvas (the consciousness). In other words, the set of branches represents the translation of the ground extending line (symbolizing a virtually infinite space) into a finite and therefore thinkable space.

The set of branches evokes a composite unity that takes into account both the multiplicity of the Natural and the need for concentration into a unity of the Spiritual.

The ground line becomes a set of branches which then flows back towards the ground line from which the trunk and the branches had formed. An extended multiplicity turns into an all-encompassed synthesis and this re-opens to multiplicity. It is indeed a circular process. Circularity seems to be reasserted by a circle that can be seen in the upper right section.

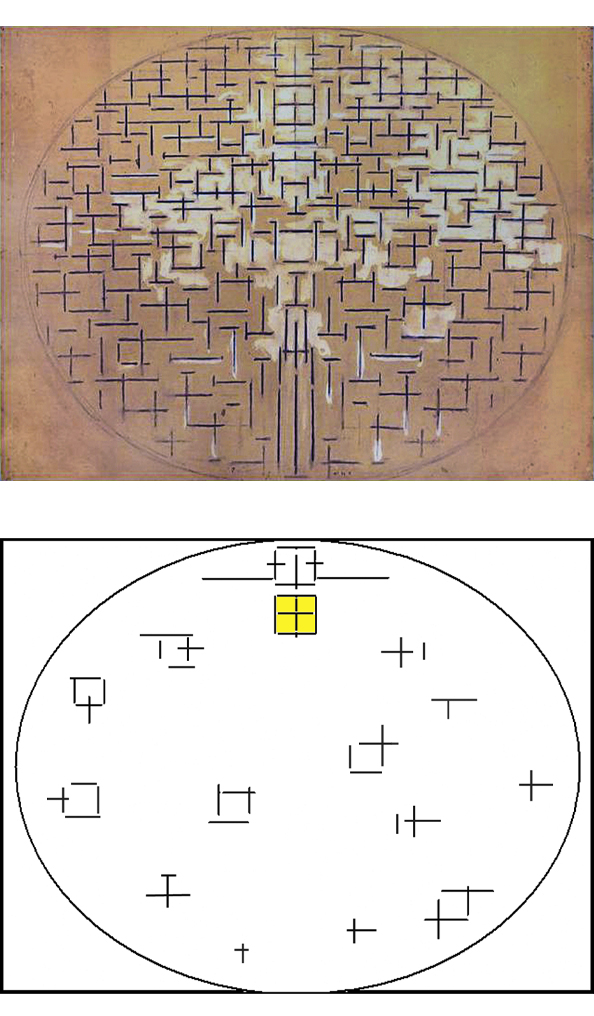

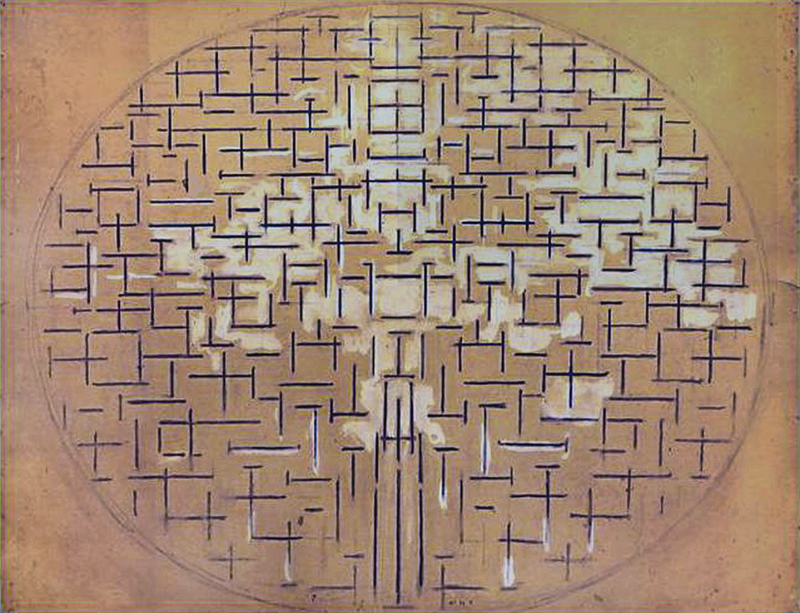

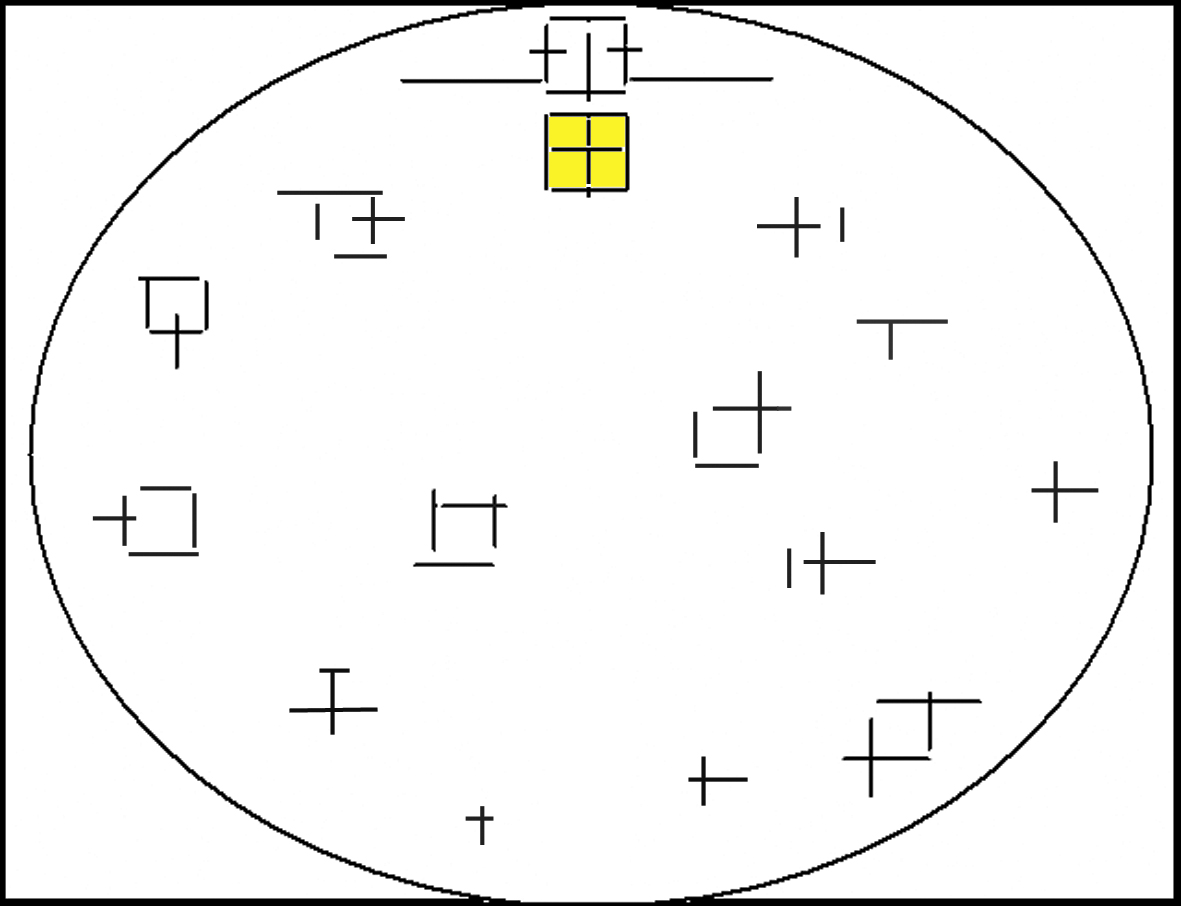

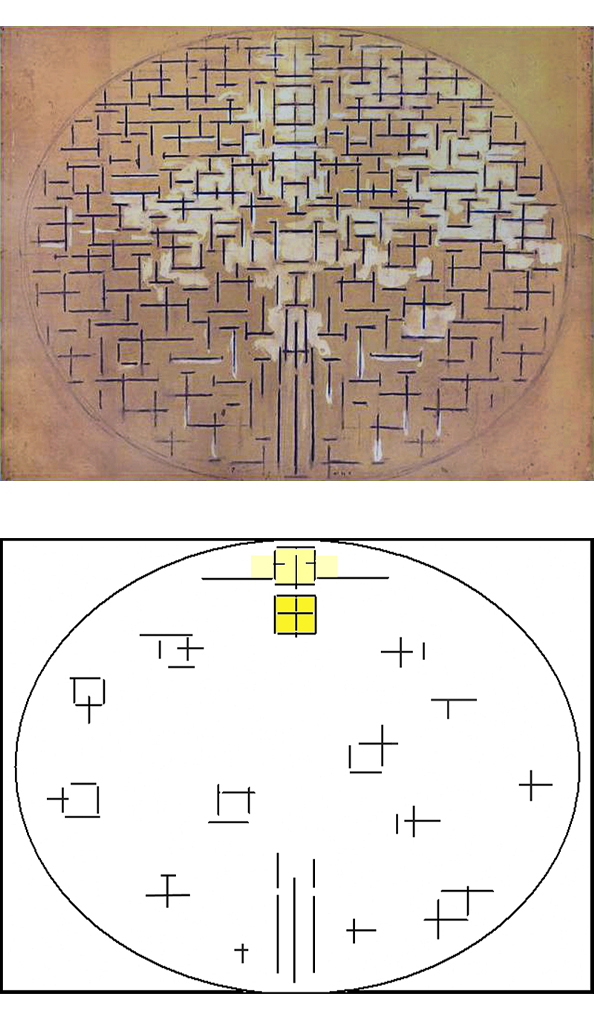

Pier and Ocean 5

About five years later we find the same idea of the manifold becoming one and then turning manifold again in a new work that although inspired by a landscape, is already in fact an abstract composition. The work belongs to a series of drawings, and gouaches inspired by a pier jutting out from the beach into the sea.

From the painter’s point of view the pier appears as a vertical (same as the vertical volumes of mills, lighthouses and church towers of the previous period) which interpenetrate with the horizontal flow of the sea (analogous to the dominant horizontal space of the landscapes and seascapes of previous years):

The interaction between the upward vertical progression of the pier (recalling the tree trunk) and the horizontal expansion of the sea (reminiscent of the ground line in the figure of the tree) generates now a whole variety of relationships between horizontals and verticals where something changes every instant:

Some horizontal and vertical signs tend to relate in the form of probable squares that finally reach precise square proportions in the upper central area. The variety of unstable signs find a more balanced and lasting situation in a fully achieved square where the opposite directions assume the same size, i.e., the same value.

In that square the contrasting duality which animates the whole composition is transformed into an ideal unity.

Think about how often conflicting drives and ideas fragment the unity of consciousness and how rare, on the other hand, are the moments when we are able to find a synthesis that takes into account the totality of ourselves.

Same as the tree trunk, which unifies the set of capricious set of branches, the square unifies now a variety of ever-changing orthogonal signs.

By reducing reality to a multitude of orthogonal signs, Mondrian performs an arbitrary operation with respect to everything we see. This enables him, however, to express the greatest possible variety on the canvas while at the same time maintaining something more constant. Every sign differs in fact from the others but they all share the same intimate nature (the perpendicular relationship), just as every human being, every animal or tree is unique and unrepeatable but all express some fundamental characteristics that make it possible to discern an invisible overall design.

“There is a common design to all things, plants, trees, animals, humans and it is with this design that we should be in consonance” (Henri Matisse).

The “landscape” on which the abstract vision is concentrated overlooks the peculiar aspect of each individual thing so as to focus on what different things have in common. As Mondrian was to put it, “Art must express the universal”.

In Pier and Ocean 5 the achievement of a perfect balance between opposites is revealed within the central square and thus suggests an inner space. The square appears as a plastic symbol of the unifying consciousness dealing with the multifarious aspect of the outer world as well as with the contradictory impulses governing our inner space both symbolized here by a multitude of different relationships between opposites drives which never really attain a full balance. The transience nature of outer / inner reality is instead captured in a more stable synthesis within the central square.

It is, however, obvious that the consciousness can only produce partial syntheses; it clearly cannot exhaust all the possible relations with the external / internal worlds. Every synthesis generated by thought is necessarily partial and temporary, and must therefore open up again to the multiform and ever-changing aspect of reality. This is what all sensible people do when they call their certainties into question in the light of experience. This is what philosophy has been doing for centuries, as have the arts and above all the experimental sciences.

A second square can be seen in Pier and Ocean 5 above the square that we have identified as a unitary synthesis of the whole composition:

Inside the second square we see a vertical segment, like the one we have in the square below, while the horizontal segment is now split into two shorter sections that extend beyond the boundary of the square to the right and left. The two small horizontal segments form two cross-shaped marks with the two vertical sides of the square. These two cross-shaped marks tell us that unity is opening up to duality.

The unitary synthesis achieved in the lower square in the form of a perfect balance between opposites (Mondrian used to say “equivalence of opposites”) is broken up into a duality that then flows back toward the variety of different situations marked again by the alternating predominance of one direction or the other.

The unity generated with the first square opens up again to manifold space with the second. The composition evokes this way the manifold and controversial space of life which attains measure and a harmonious condition in the space of consciousness (the square) before opening up again to the controversial outer – inner reality and unforeseeable events of life.

I recall the ideal circular process that we have observed in the figure of the tree where, through the unifying action of a vertical trunk, the horizontal extension of the ground (a virtually infinite space) becomes a set of branches (a finite space) that then flows back to the right towards the continuous line of the ground.

In a different way we see now an analogous circular process in Pier and Ocean 5 where the horizontal extended sea (a virtually infinite space) is concentrated by a vertical pier into a entral square (a finite, balanced synthesis) which then opens higher up to the horizontal before flowing back towards manifold space. In both works multiplicity becomes unity and then unity turns back into multiplicity.

Unity and multiplicity, permanent and mutable, i.e., the Spiritual and the Natural are commonly considered as opposite aspects that Mondrian would like to show simultaneously as if they actually would be one and the same thing observed from different viewpoints. I have used the example of a tree looking like a simple patch of green when observed from a certain distance but revealing a far more complex structure on closer examination. Moving in the opposite direction, the complex structure of a tree once again returns to a condensed patch of color. Unity reveals endless multiplicity and multiplicity reverts to unity.

There is a constant alternation of unity and multiplicity in our experience of everyday life. It depends on our point of observation if one thing looks small and simple or large and complex. This applies not only in observing tangible things around us but also in considering existential and psychological situations. Indeed, we often tend to simplify or unify what is actually far more articulated and complex.

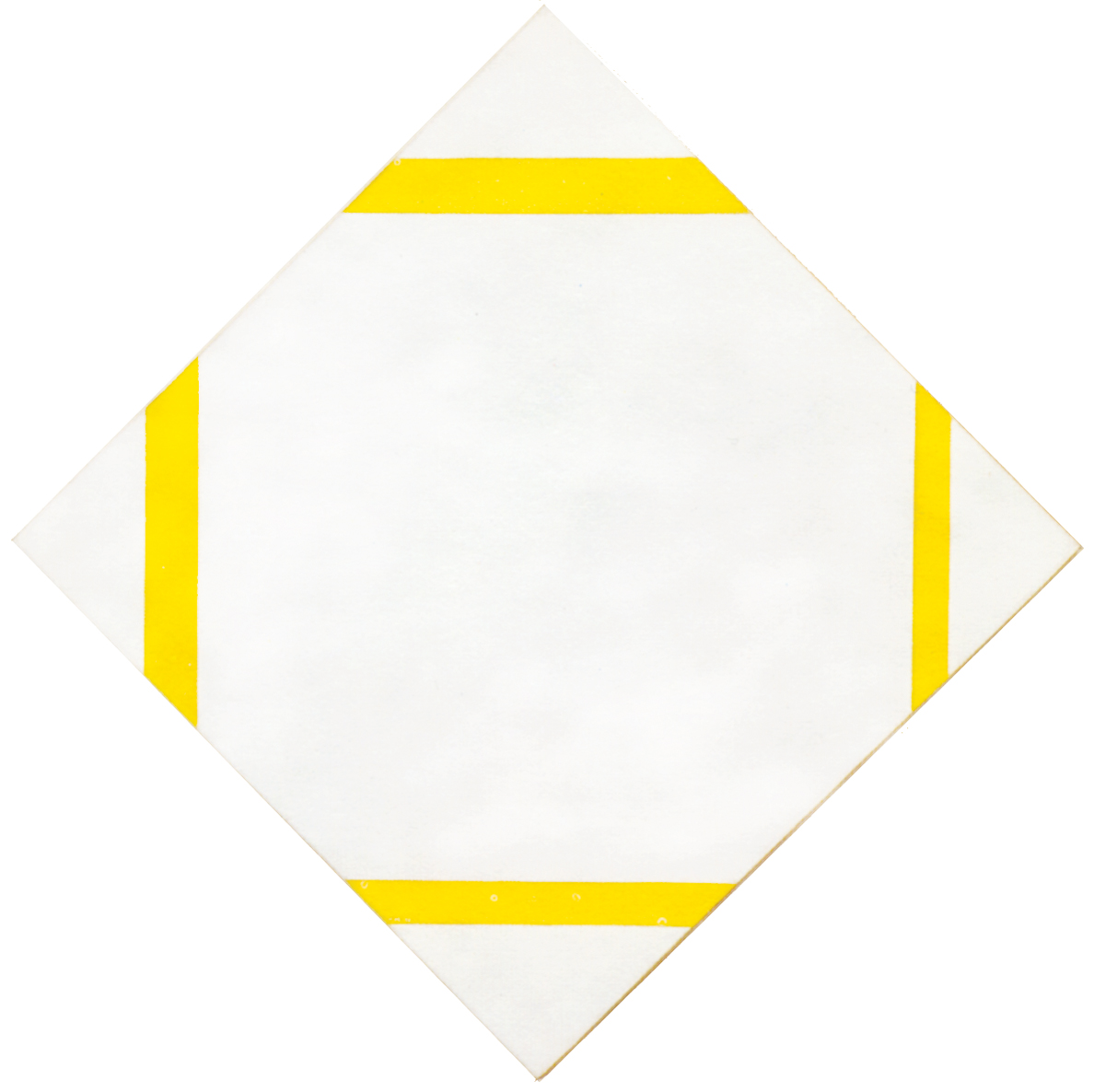

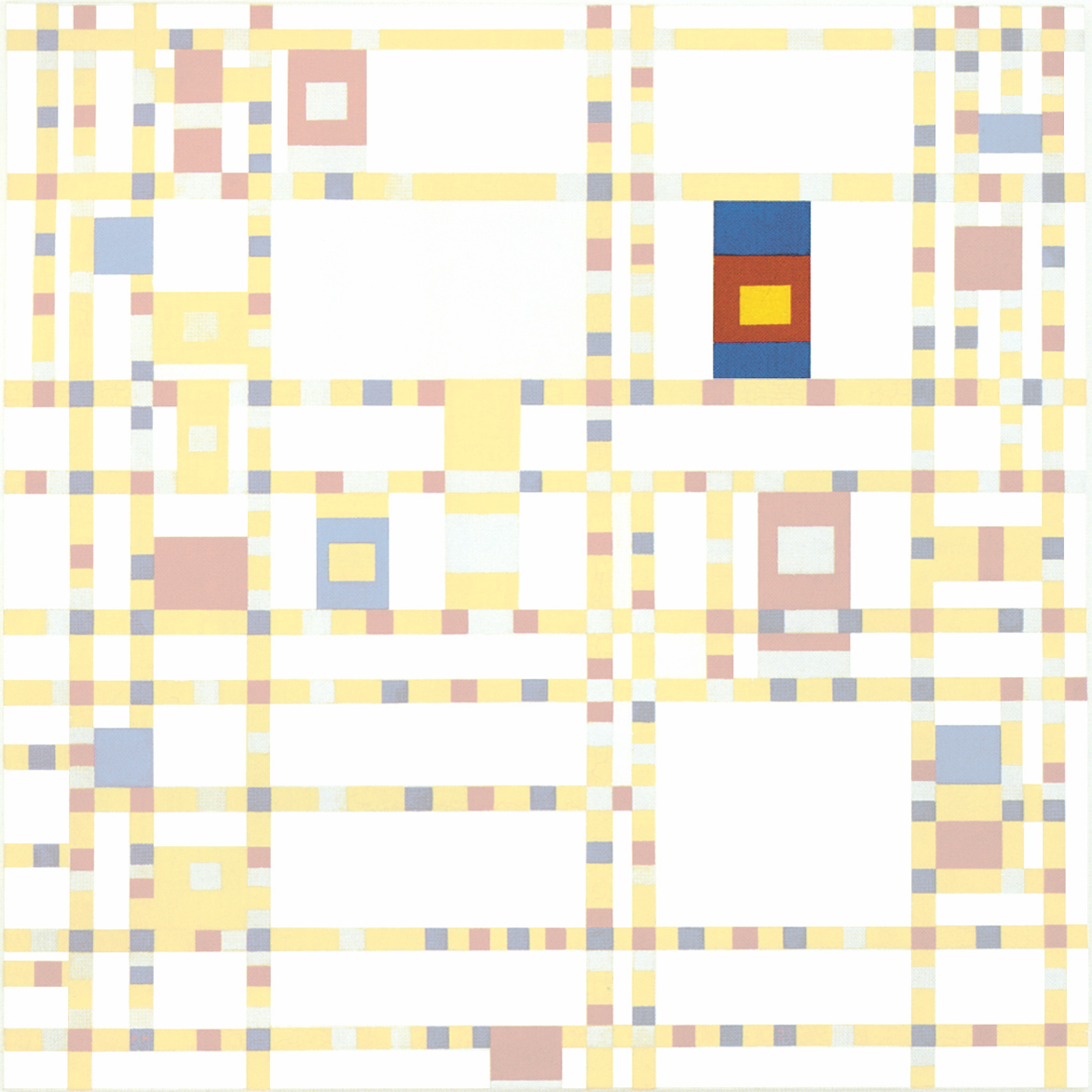

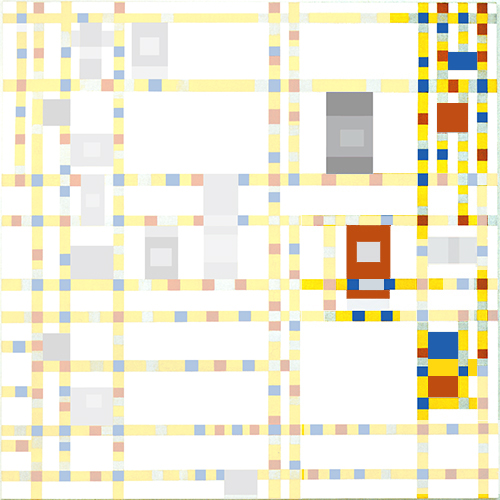

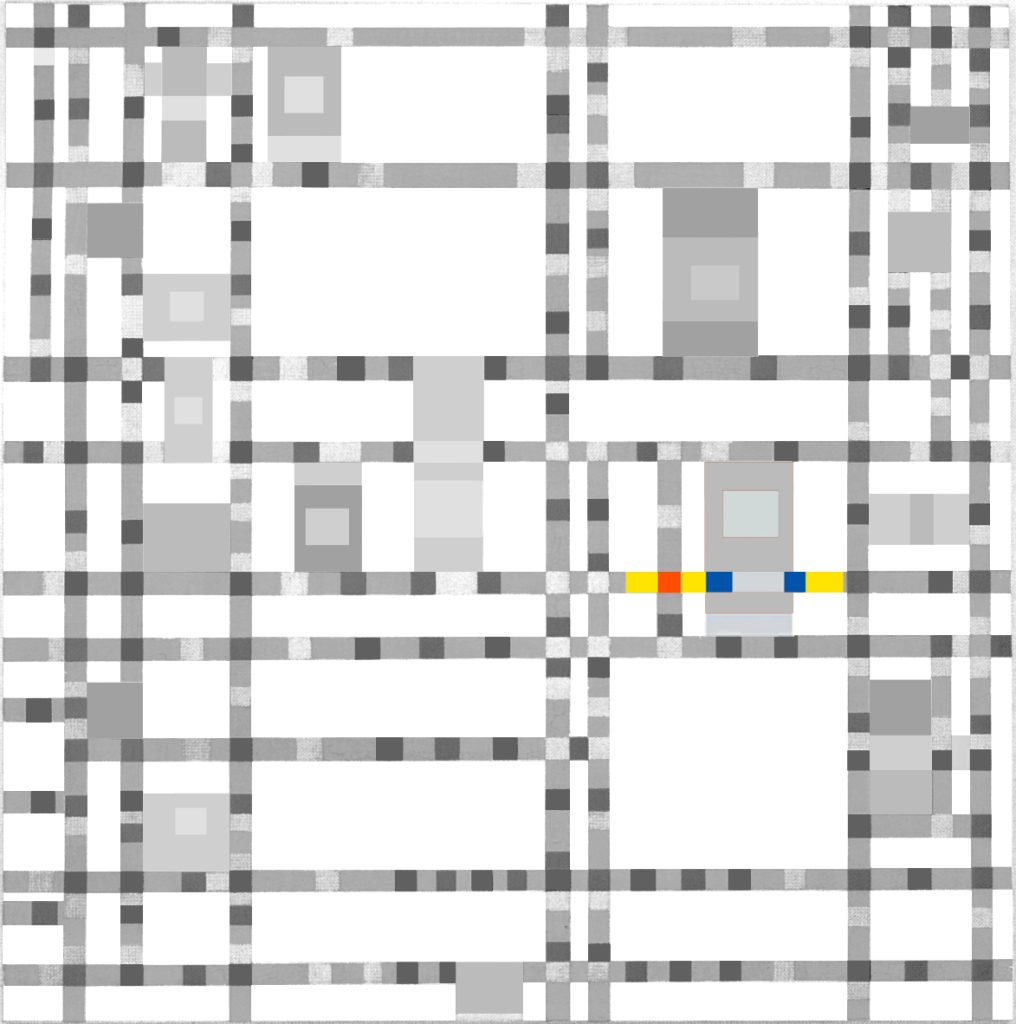

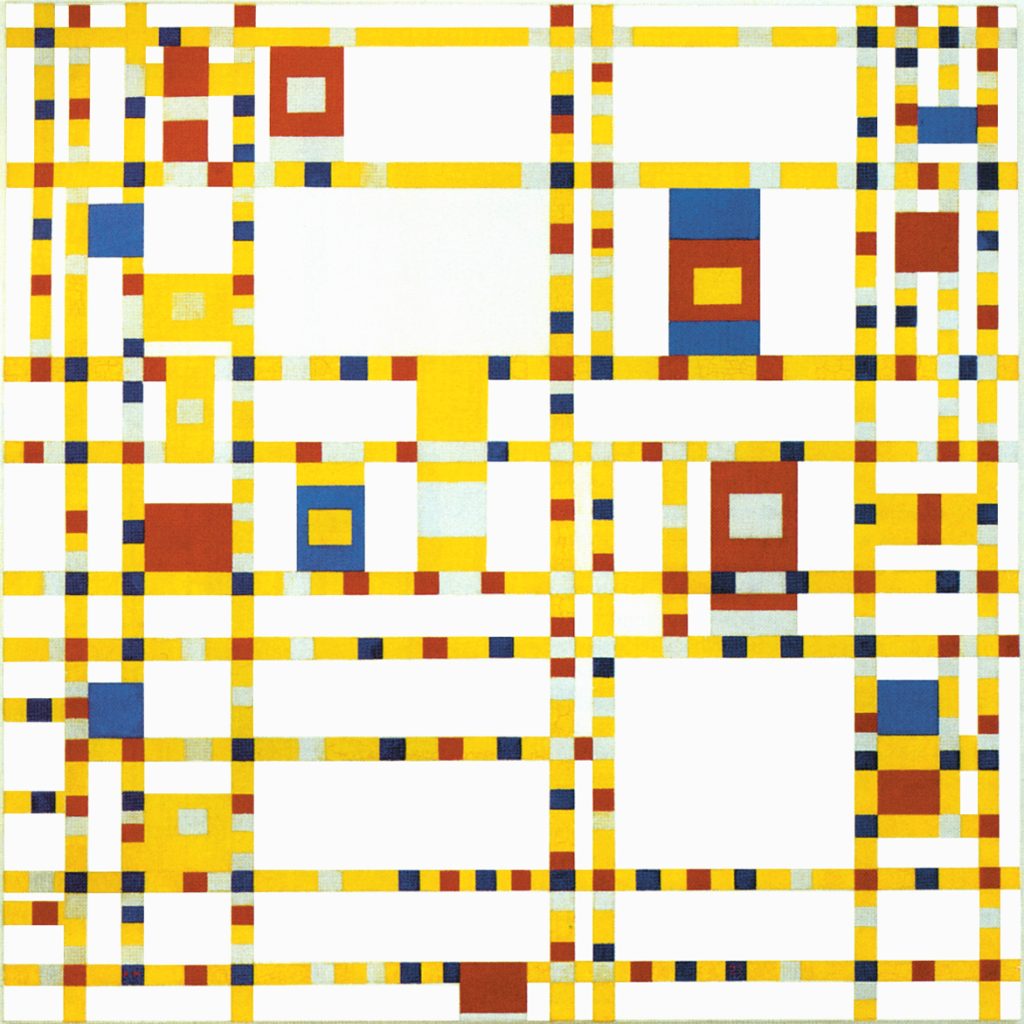

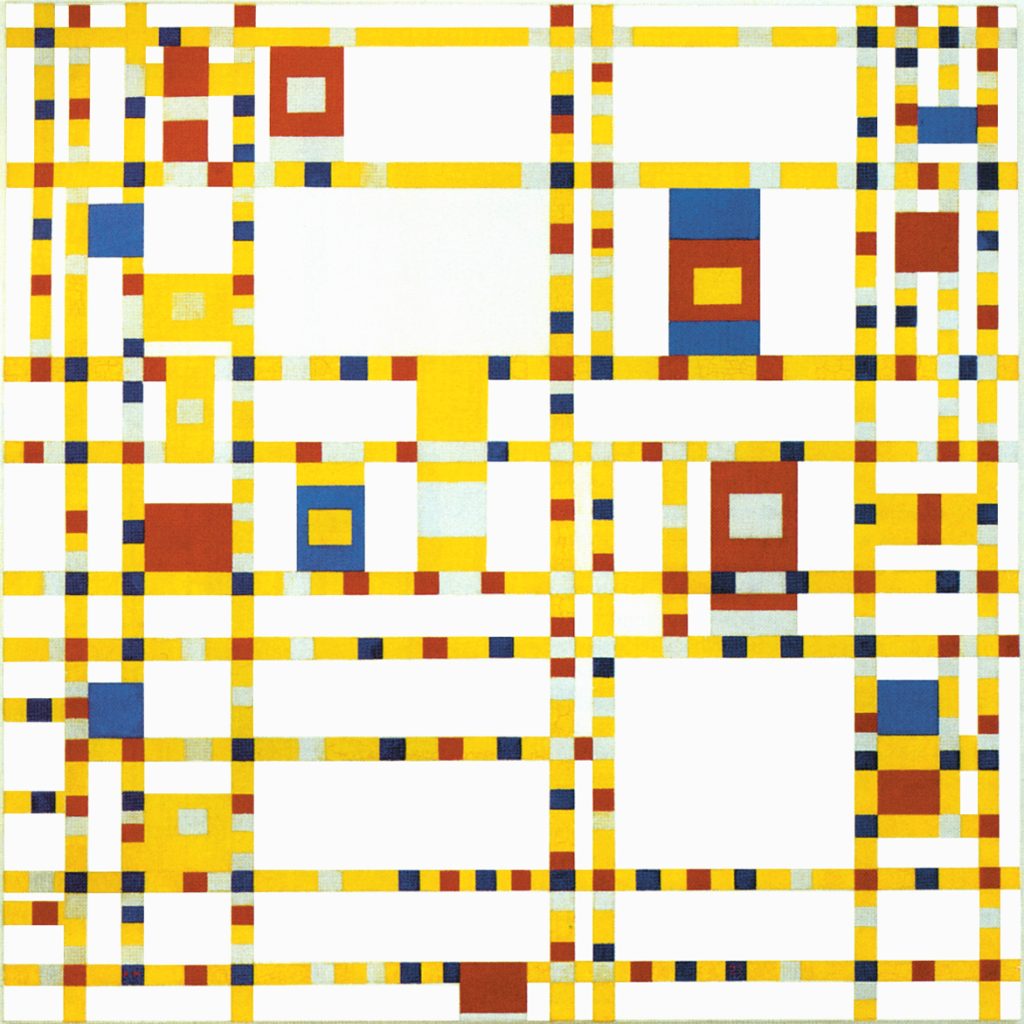

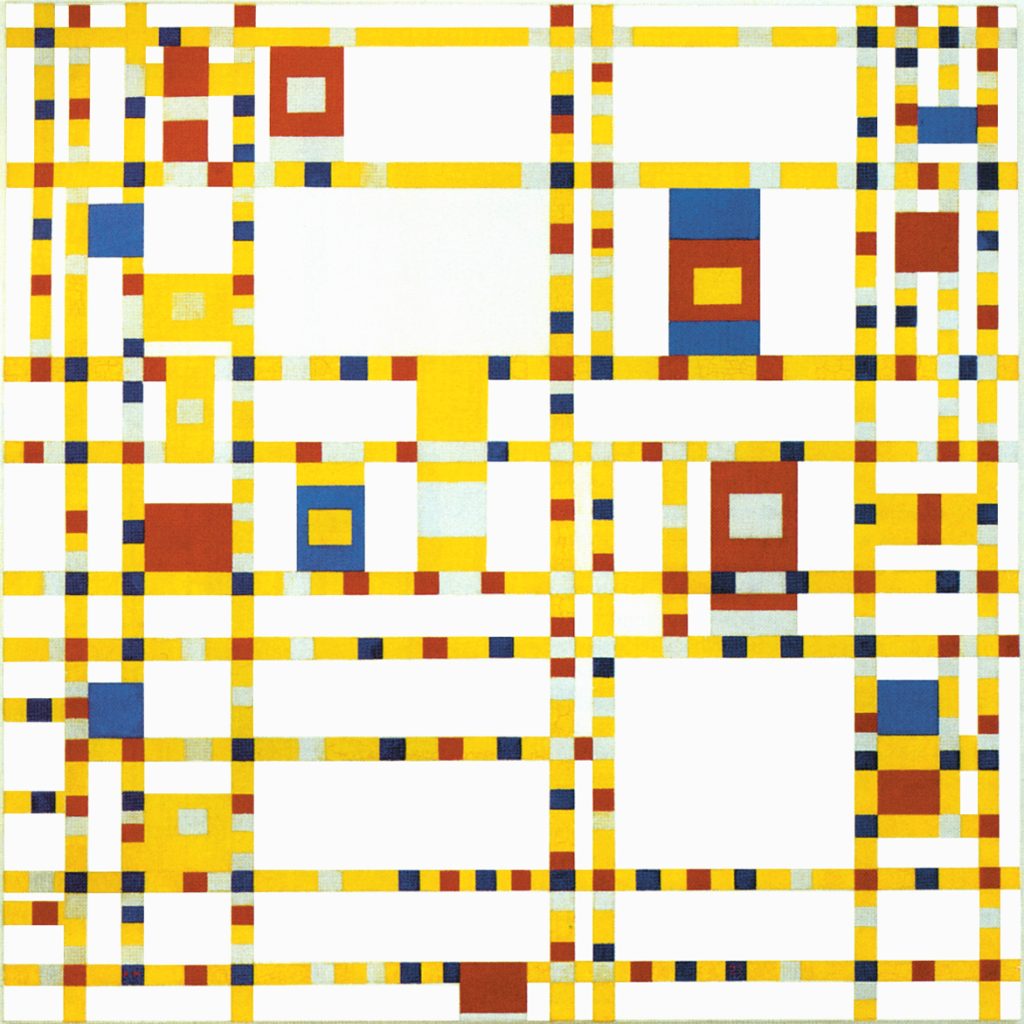

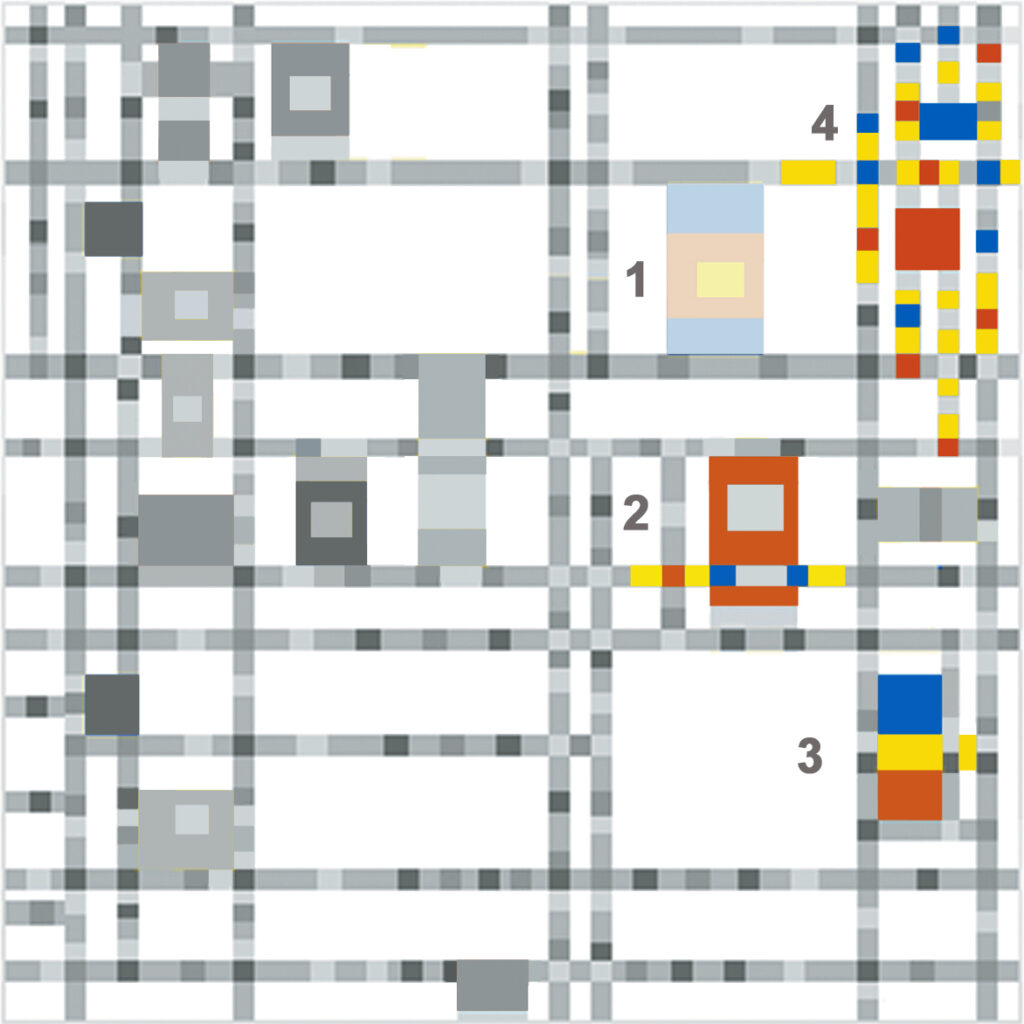

Broadway Boogie Woogie

We shall now examine the third work which, after thirty-five years from The Red Tree and twenty-seven years from Pier and Ocean 5, shows in a totally new way the same process from multiplicity to unity and from unity to multiplicity.

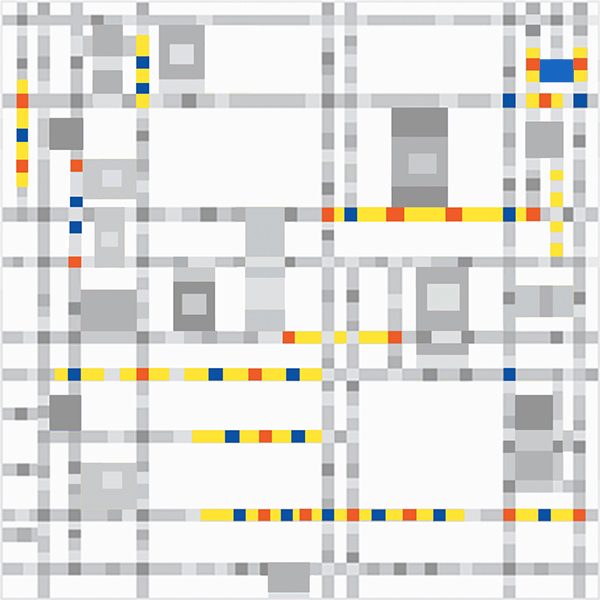

At first glance we see here a multitude of small gray, yellow, red, and blue fragments randomly moving along straight lines:

Oil on Canvas, cm. 127 x 127

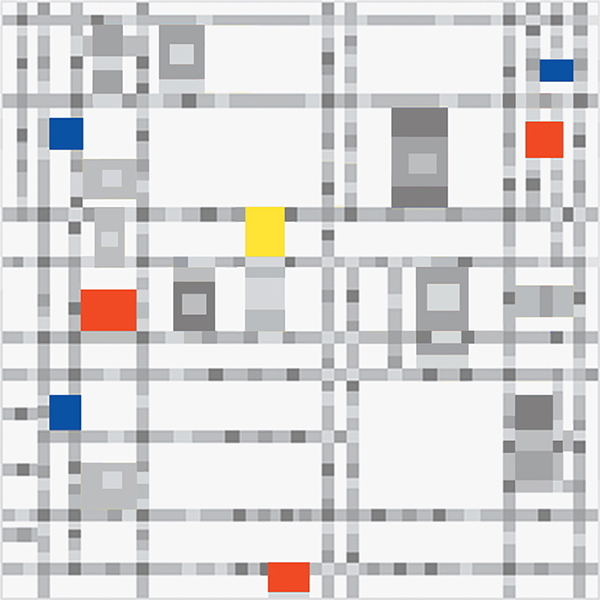

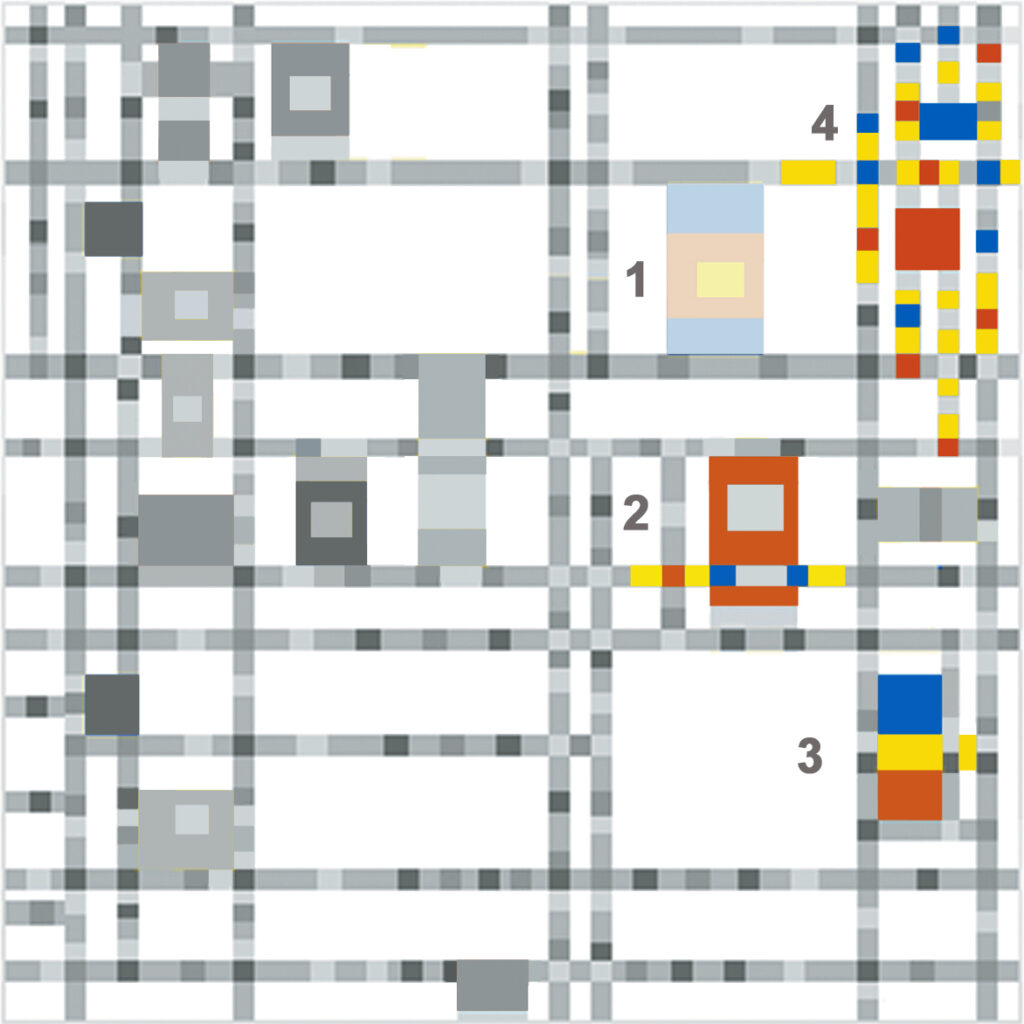

Observation of the frenzied succession of fragments reveals some that join up with others to generate some symmetrical configurations along the lines (Diagram B).

The symmetrical sequences present an orderly rhythm generated by a repeated alternation of same colors:

A horizontal relationship between two vertical symmetries generates a small blue plane in the upper right corner (Diagram A) which is followed by other planes of different color and shape (Diagram B). The relationship between the opposite directions appears more stable and durable in the planes than in the initial fragments moving within the lines:

New planes are born, as shown by diagram C, that differ from the ones observed in diagram B by presenting an inner space made of two colors:

From the planes of diagram C onward, we observe a process of internalization from the dynamic and fragmentary space of the straight lines toward a more permanent and balanced space that is generated within some planes.

Diagram D shows how the self-internalization of space continues with a further growth of planes both in extent and color consistency. The three primary colors concentrate now in the area of just two planes while to the right we see a single large plane in which the three primary colors interpenetrate to form a compact unity:

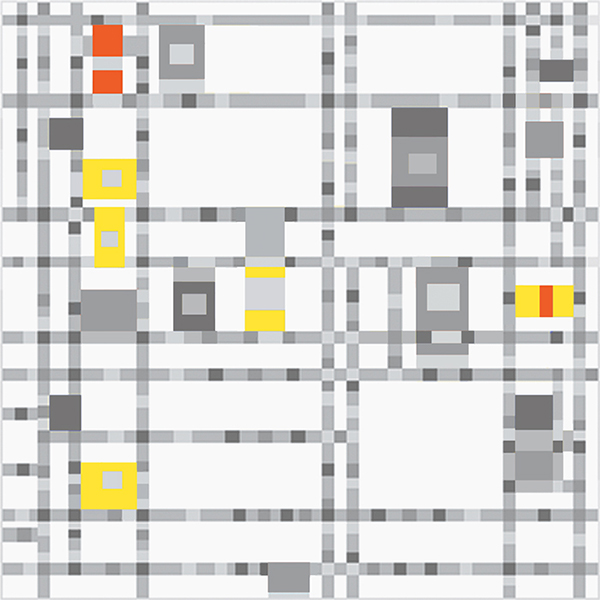

The manifold space made of yellow, red and blue fragments randomly expanding within opposite lines, which disrupted our visual field at the beginning of the process by keeping the eye in constant motion, attain now a unitary synthesis (Diagram E):

Space undergoes uninterrupted transformation from a condition of multiplicity to one of unity.

Same as the tree trunk unifying the set of branches in The Red Tree and the fully achieved balanced central square unifying a set of imbalanced relationships between horizontals and verticals in Pier and Ocean 5 , the unitary plane in Broadway Boogie Woogie is a plastic symbol of the unifying consciousness of man dealing with our multifarious and constantly changing outer and inner worlds symbolized here by a variety of fragments dispersed along never-ending straight lines. Because it is abstract, the painting can function as a plastic symbol of the outer and inner worlds of any different person.

The controversial and virtually infinite space of the lines is transformed into a finite and more lasting space with the unitary plane.

It would, however, be a mistake to see this as a permanent situation. The unitary plane should rather be seen as a temporary balanced synthesis which, like the square of Pier and Ocean 5 reopens to the manifold space around, as we shall now see in diagram F.

Plane 2 is the same size as plane 1 but consists solely of red and gray rather than the three primary colors. Moreover the horizontal line running suddenly through the vertical plane tends visually to disrupt the previously attained balanced interpenetration of horizontal and vertical achieved in plane 1:

After the equivalence of the opposite directions and the synthesis of the three primary colors attained in plane 1, the colors are again reduced in plane 2 and the external dynamism of the lines reappears to generate new opposition. After the degree of comparative calm, constancy, and unity achieved in plane 1, spatial movement thus seems to reappear in plane 2.

The indication provided by plane 2 finds further confirmation in plane 3, where blue, yellow, and red are juxtaposed but no longer interpenetrate as they did in plane 1. The juxtaposition produces the impression of three separate planes, whereas the interpenetration combines the three colors in a single structure of greater stability. Note how the yellow on the right of plane 3 already seeks to cross the perimeter of the plane and flow into the yellow of the surrounding lines. Plane 3 can therefore be seen as plane 1 in the process of dissolution:

Configuration 4 possibly represents the conclusion of the process of reopening the unitary synthesis in that it can be seen as a continuation of the disintegration of 3.

Space proceeds from a comparatively static and wholly internal condition (1) toward one of growing instability (2) that is gradually transformed into the more dynamic and variable external space of the lines (3, 4).

A multiplicity of yellow, red and blue fragments concentrates in a synthesis of those three colors (Diagram E) and then reopens to the multiple (Diagram F):

From expansion toward increasing concentration (Diagram E) and then from concentration back to expansion (Diagram F). This is the way Broadway Boogie Woogie breathes. Through a dynamic process the one and the many, i.e., the unity invoked by the Spiritual and the multiplicity presented by the Natural, merge and transform into each other.

For a detailed examination of Broadway Boogie Woogie see this.

From the image of a tree, which expresses the relationship between multiplicity and unity in a metaphorical way, toward an image of a stylized pier extended toward the sea to a completely abstract image that, as such, acquires a universal significance that no longer applies only to a tree or a pier but to all possible things. “Art must express the universal” (Mondrian)

A circular process

The Red Tree (1908-10), Pier and Ocean 5 (1915) and Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942-43) show a similar process from multiplicity to unity and from unity to multiplicity, that is to say, a circular process. Please note how in all the three paintings the horizontal opens up the concentration previously exercised by the vertical:

The horizontal (symbol of the natural) re-opens the synthesis generated by the unifying action of the vertical (the spiritual).

Broadway Boogie Woogie expresses in the clearest form and most vivid colors the basic idea that has guided the artist for an entire existence.

“Life is a continued examination of the same thing in ever-greater depth” (Mondrian)

“The evolution of his work is certainly the most eloquent of this century. I know of no other example of such acute finalism.” (Seuphor)

A dynamic unity

The unity that Mondrian strove to express is a temporary synthesis generated momentarily by the subject in its changing relationships with the world. It is not something to be attained once and for all. Searching for equilibrium between the outer and inner worlds does not mean attaining fixed points and immutable truths. The square of Pier and Ocean 5 and the unitary plane of Broadway Boogie Woogie are not static and all-inclusive unities but dynamic ones intrinsically linked to the manifold space in which they are born and toward which they return.

True reality

From the metaphorical figure of a tree (1910) to a concrete image showing a relationship between multiplicity and unity in the clearest way (1943). It is a process that lasted over thirty years, aimed at the construction of a plastic space through which to see reality in a new way. A Copernican revolution with respect to art, which until the end of nineteenth century focused on the semblances of the external world, that is, on the so-called figurative painting. The idea of the manifold becoming one and the one then turning manifold expresses a new conception of reality where every single thing is considered at the same time as one and manifold, finite and infinite.

Micro and macrocosm

“Reality is not as it appears to us“ explains scientist and philosopher of science Carlo Rovelli in his book of the same name.

What we call reality is only a part of true reality. Our senses do not grasp the microcosm that generates and is the substance of everything we see and touch. Everything, from minerals to plants, animals and human beings which we perceive as individual units are actually a multiplicity of parts each composed in turn of tissues, cells and atoms. Every single thing unveils a very complex and virtually infinite reality that we do not actually perceive.

“Yes, the one is one only in appearance: it is part of the whole and is at the same time a whole composed of parts… Each thing shows in smallness again the whole. The microcosm is equal in composition to the macrocosm, says the sage.” (Mondrian)

Painting certainly means taking into account the visible, but today it also means considering the visible as the emerging part of a truer and more complete reality. In accounting for both the apparent shapes and an invisible basic structure common to all things, painting regain a universal view of reality.

The above indicates the overcoming of the concept of nature as the only part that we are able to perceive and its extension to the microcosm, that is to say, the foundations of life. It seems to me rather naive to call painting that imitates semblances realistic and to brand as incomprehensible that which, by widening the gaze, suggests the part of reality not directly accessible to us as well.

“Art makes visible the invisible.” (Paul Klee)

Even the distinction between fullness and emptiness no longer makes sense since “emptiness” is just a different concentration of the same energy that generates “fullness.” How to simultaneously evoke external and inner worlds, visible and invisible, macrocosm and microcosm except in abstract form?

An abstract “landscape”

The “landscape” we should be concerned with today goes from the intimate common structure of things (microcosm) to what we see around us (our sense of nature), up to the unreachable infinite macrocosm our planet is part of. What is all of this if not the result of endless combinations of the same basic elements.

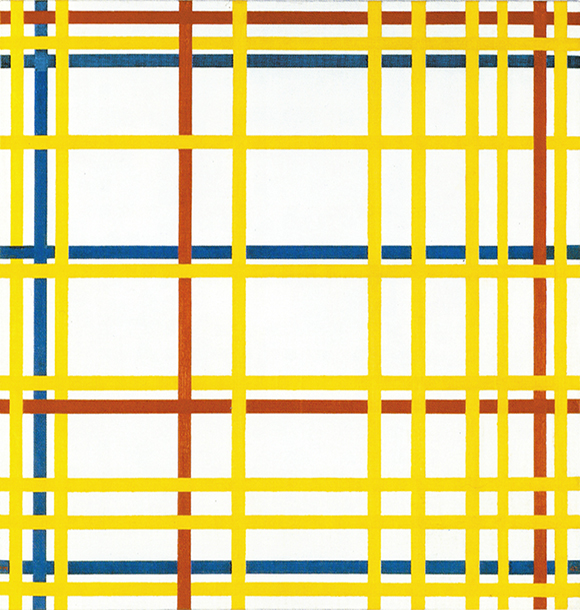

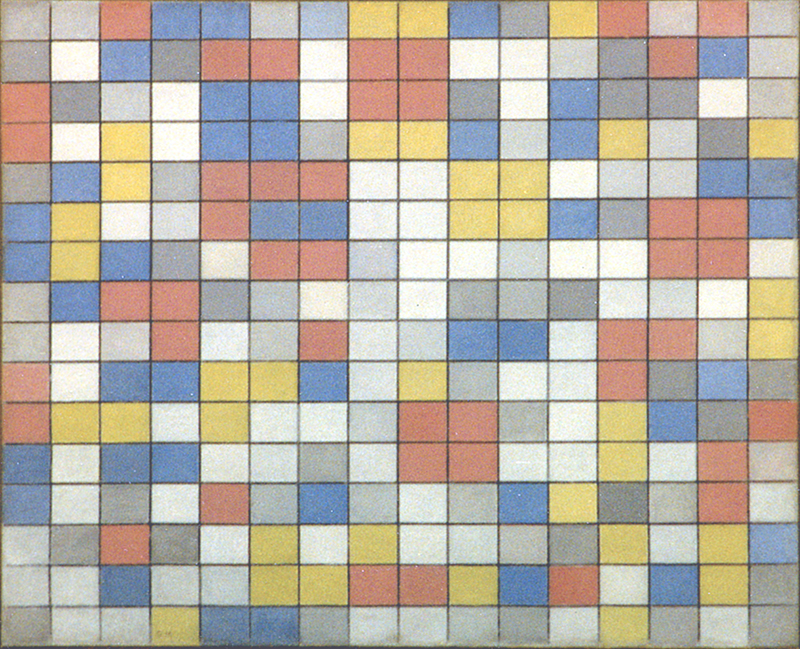

To make just one example of what I mean by “landscape we should be concerned with today”, let us consider a composition Mondrian painted in 1919: It consists of basic elements such as same size rectangles which generate a regular and symmetrical layout in terms of form that is transformed by the alternation of the three primary colors into an asymmetric whole of highly variable appearance:

Isn’t nature an infinite variation of entities born out of always new and different combinations of same basic elements? Hydrogen and helium, oxygen, carbon, neon, iron, nitrogen, silicon, magnesium, sulfur and others. Everything that takes shape around us consists of these elements.

Checkerboard Composition with Light Colors does not merely evoke in abstract terms the variety and changeability of the apparent forms seen in nature or in urban spaces, but suggest that every single thing, which appears different from another, actually consists of an intimate analogous structure common to all things. “There is a common design to all things, plants, trees, animals, humans, and it is with this design that one must be in consonance.” (Henri Matisse)

While photography and video tell us about the outer and mutable form of everyday things, painting reveals their intrinsic reality at a universal level.

True abstract painting means translating the multiplicity and mutability of nature and human existence into the two real and concrete dimensions of the pictorial surface. Living in such a complex reality as we do today, abstracting is essential in order to tune into the substance of things again.

Of course, to paint means first of all to give life to harmonious compositions of shapes and colors that take on a life of their own, and this happens when each part contributes to a dynamic whole that is never exhausted with itself; when everything is in its place and never in a certain and definitive way. It is not easy to explain with words when a painting becomes a work of art. In any case, however, whether it is realistic (figurative) or abstract painting, what really matters is still the same thing and that is: optimal relationships of forms and colors.

A broader spectrum of reality

The new concept of space invite us to consider reality starting from the infinite structure of microcosm and expanding towards an uncatchable macrocosm. By abstracting from appearances, that is, from a partial reality, painting can evoke in its own ways the visible and the invisible, that is, a truer reality.

“As for details, the painter no longer has to worry about them. There is photography to render a hundred times better and faster the multitude of details.” (Henri Matisse)

No longer dwelling on the outer fleeting appearance of things – for this we have today photography and video -, this kind of abstraction (not any type of abstract painting) suggests a broader spectrum of reality.

“Art must look not at the appearance of nature but at what nature really is. If we wish to fully represent nature, we are forced to look for another plastic expression. And it is precisely out of love for nature and reality that we avoid its natural appearance”. (Mondrian)

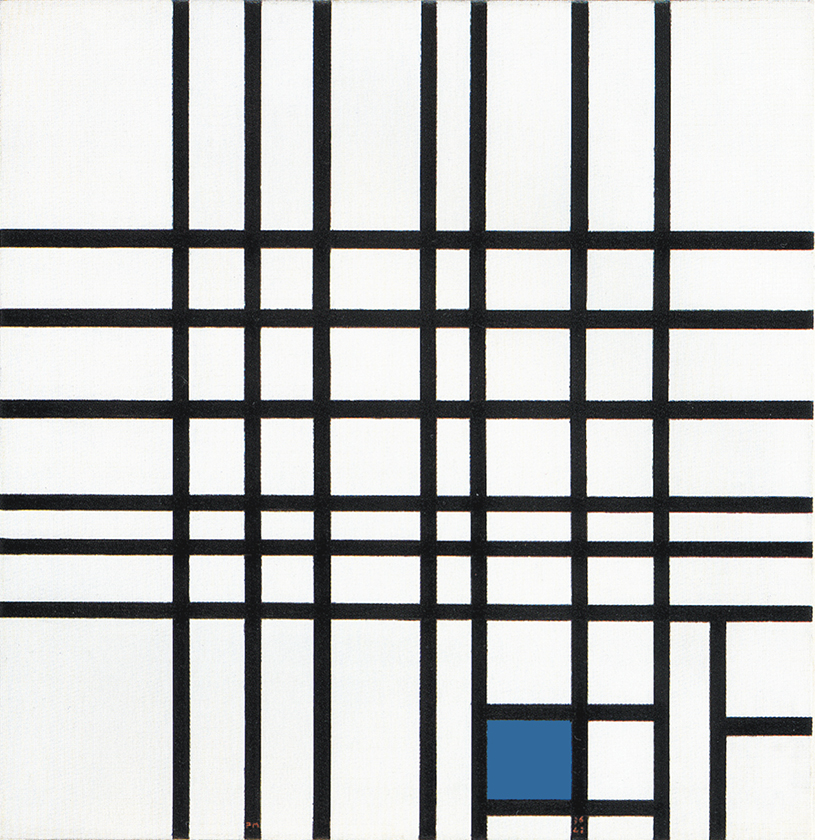

Straight lines

According to Blaise Pascal, our sense of reality generates in-between the whole and true reality which consists of an infinite microcosm and an infinite macrocosm. This is one of the reasons why in his Neoplastic compositions Mondrian use endless perpendicular lines suggesting infinite space expanding towards opposite directions:

Mondrian: “The straight line is the plastic expression of maximum speed, maximum energy and therefore leads to the abolition of time and space.”

“Time is real for us. Beyond time is the true reality, but not our reality. By means of our reality we have to come to the true reality. Hidden more or less by our reality, the true reality is always present. Progress is unveiling of the true reality.” (Mondrian)

More about the genesis of space-time from a Neoplastic point of view here.

A lasting interpretation

If by reality we mean only the way things appear to us, we would have to conclude that our world, where the appearance of things change so rapidly, reality has no lasting consistency which is, indeed, a recurrent impression today.

“Everything we see fades away. Nature is always the same but nothing remains of it, of what it appears. Our art must give the thrill of its duration, must make us taste it eternal.” (Paul Cézanne)

Henri Matisse: “Beneath the succession of moments, which makes up the superficial existence of beings and things, cladding them in shifting appearances that soon vanish, one can look for a truer, more essential character, to which the artist will cling in order to give a more lasting interpretation of reality.”

Cézanne and Matisse too, sought among the changing semblances of reality a truer reality. Cézanne tried to express a more essential character suggesting that all apparent shapes can be traced back to stereotypes such as the cylinder, a cone and a sphere; Mondrian found a key to the eternal in the perpendicular axiom of the bi-dimensional space.

Abstraction, when it is not just a convenient shortcut, restores to painting a universal gaze. This is why it seems to me that this kind of abstraction is more tuned with today’s reality than the so-called “realistic painting”.

Copyright 1989 – 2025 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More