Please note: If on devices you click on links to images and/or text that do not open if they should, just slightly scroll the screen to re-enable the function. Strange behavior of WordPress.

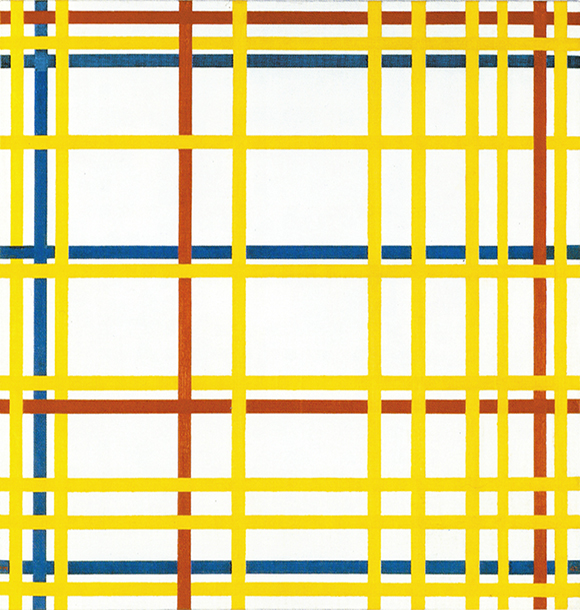

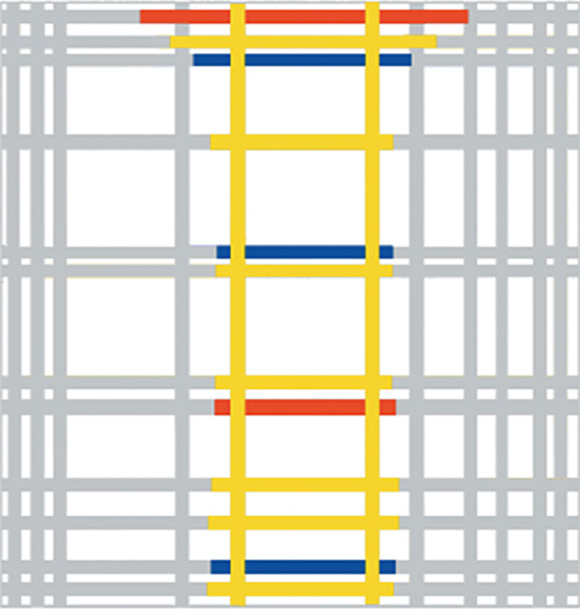

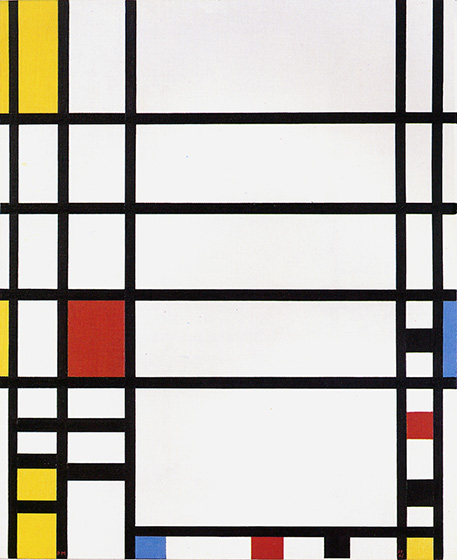

The final stages

This page examines the final stages of Neoplasticism in view of one painting, Broadway Boogie Woogie, which sums up the whole of Mondrian’s oeuvre.

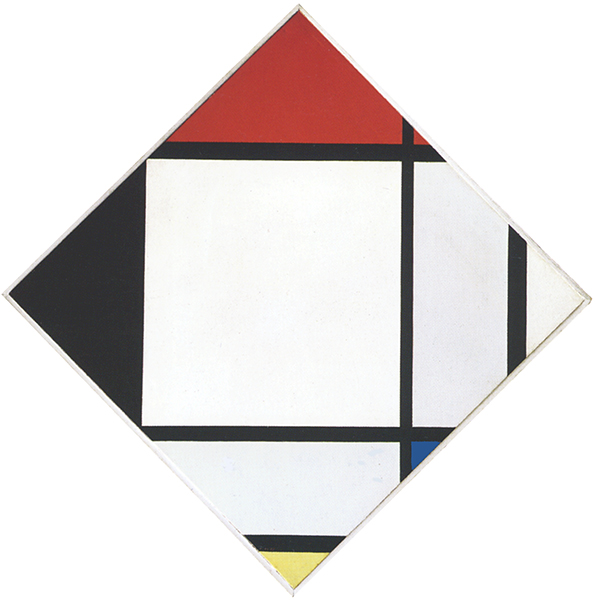

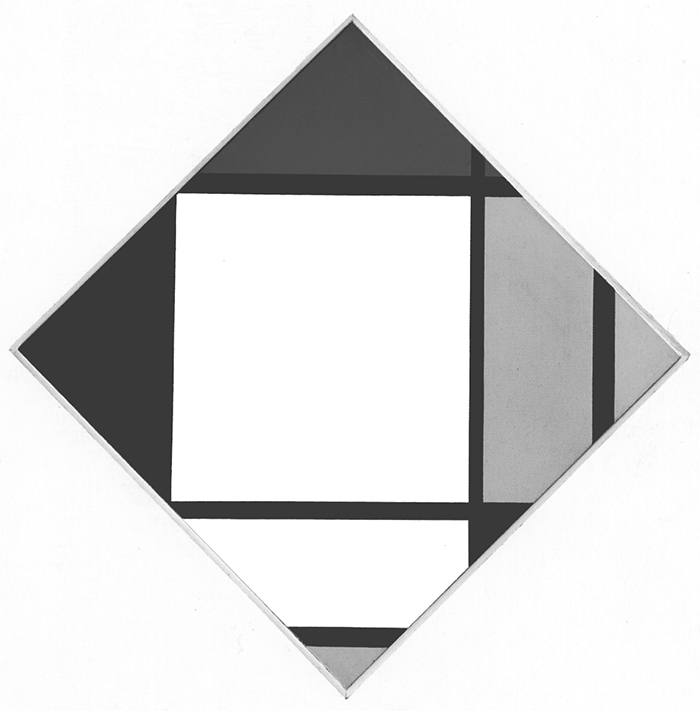

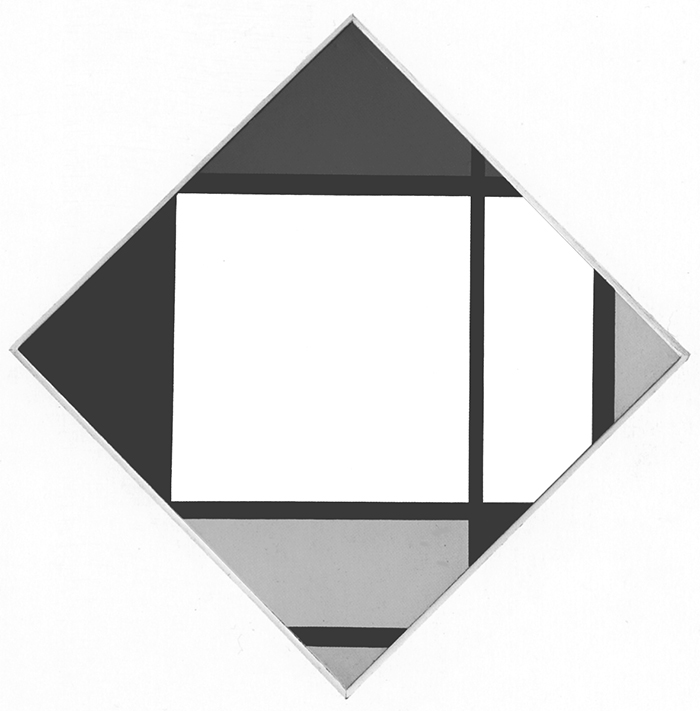

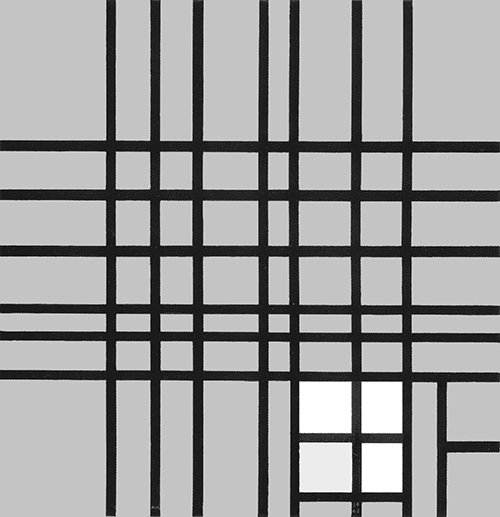

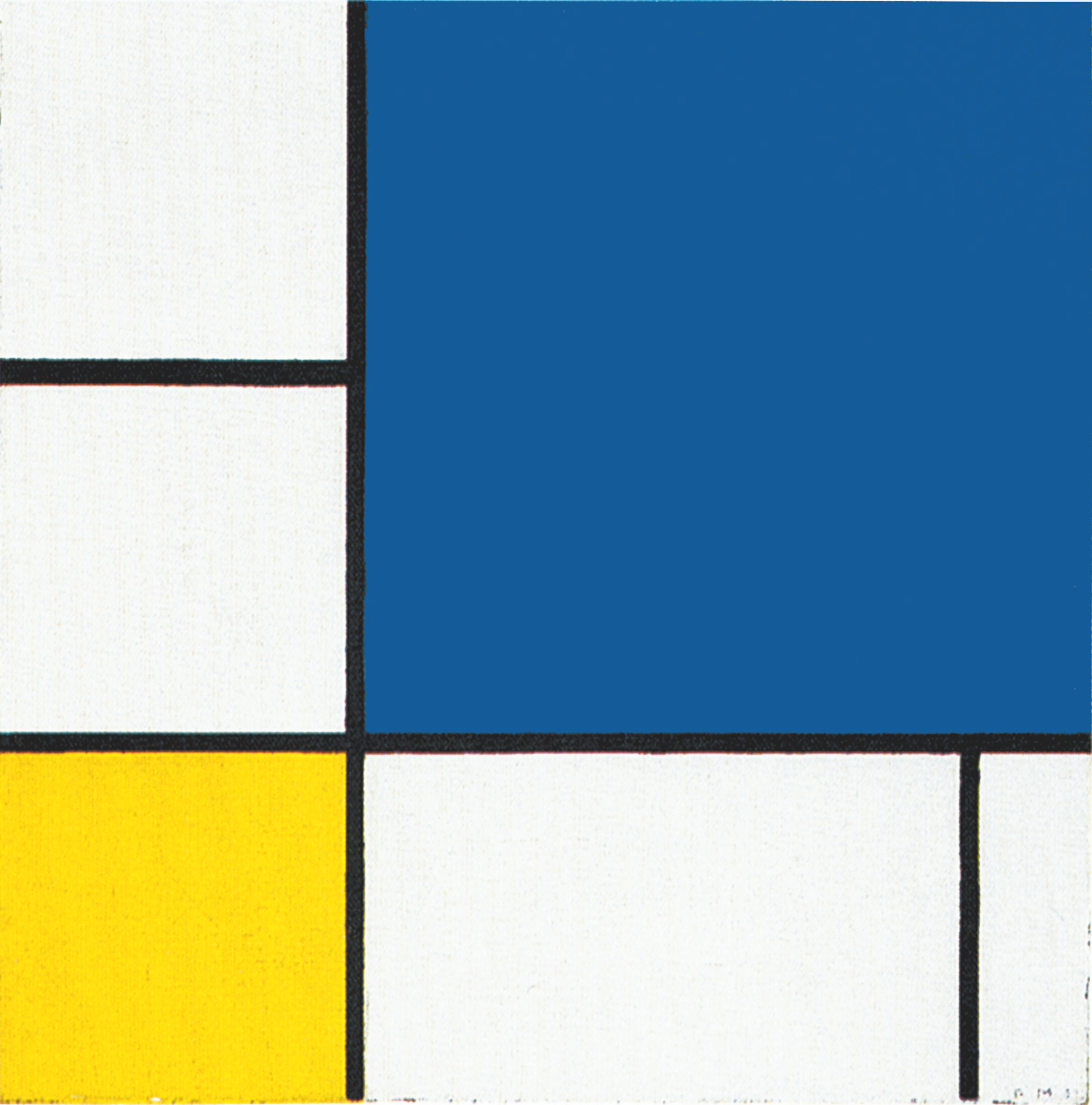

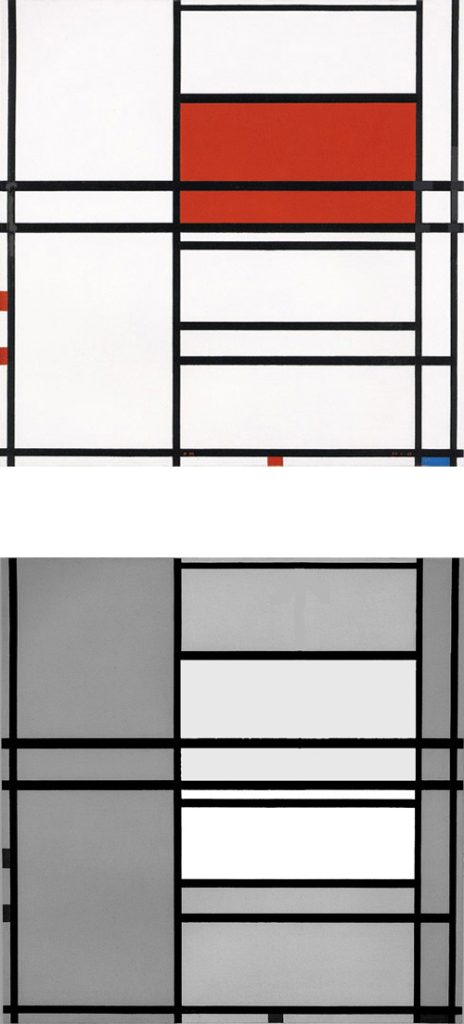

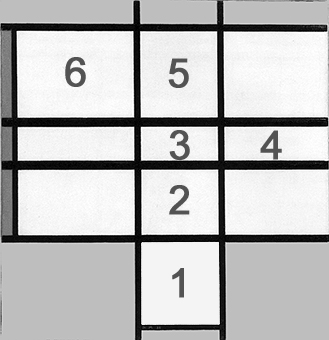

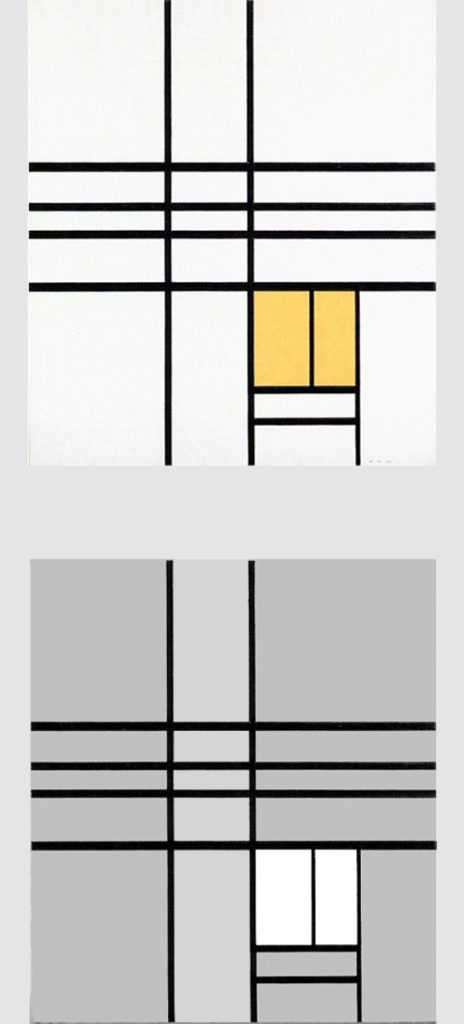

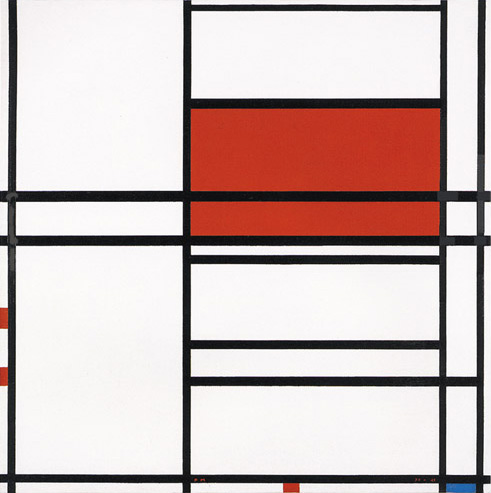

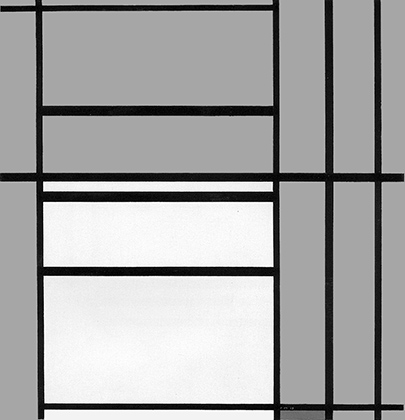

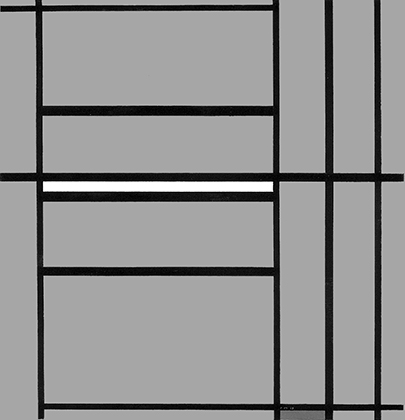

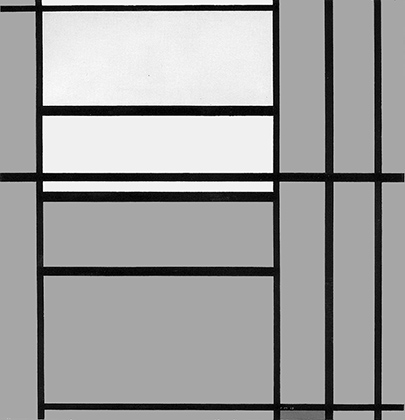

The tendency observed in the previous page toward a space of ever-greater rarefaction and synthesis:

gradually gave way to the opposite tendency, whereby an increasing level of articulation and complexity was progressively reintroduced into the Neoplastic canvases as from 1934:

Observation of the above four works in sequential order reveals a gradual increase in the number of lines, which divide the space of the canvas into a growing number of parts.

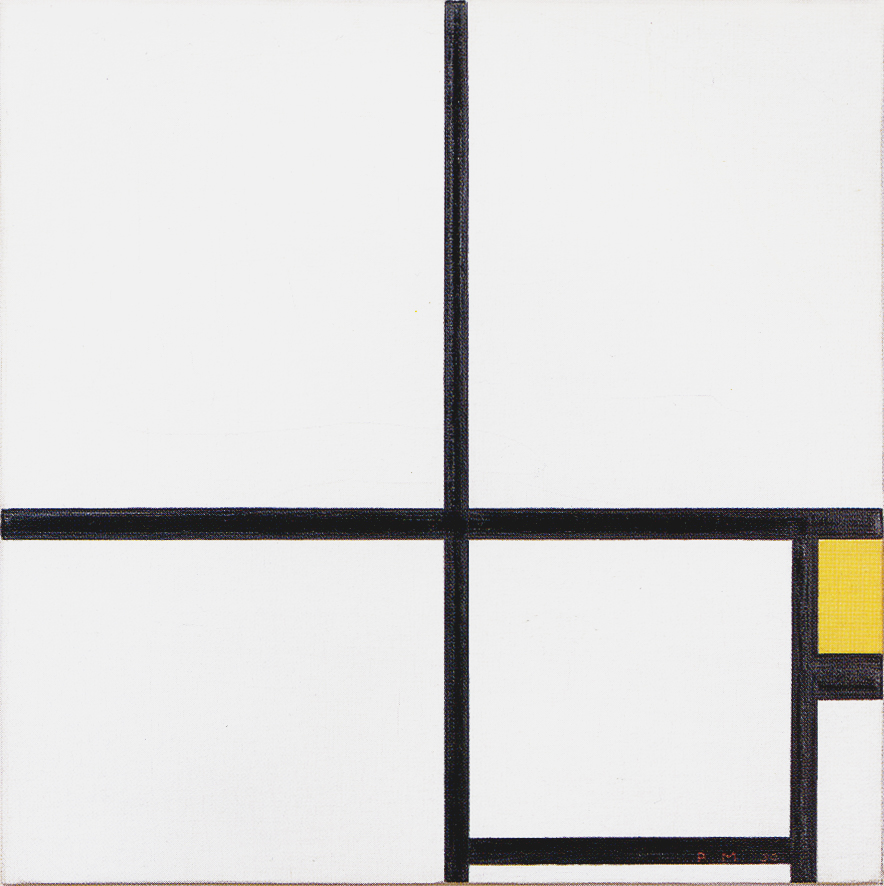

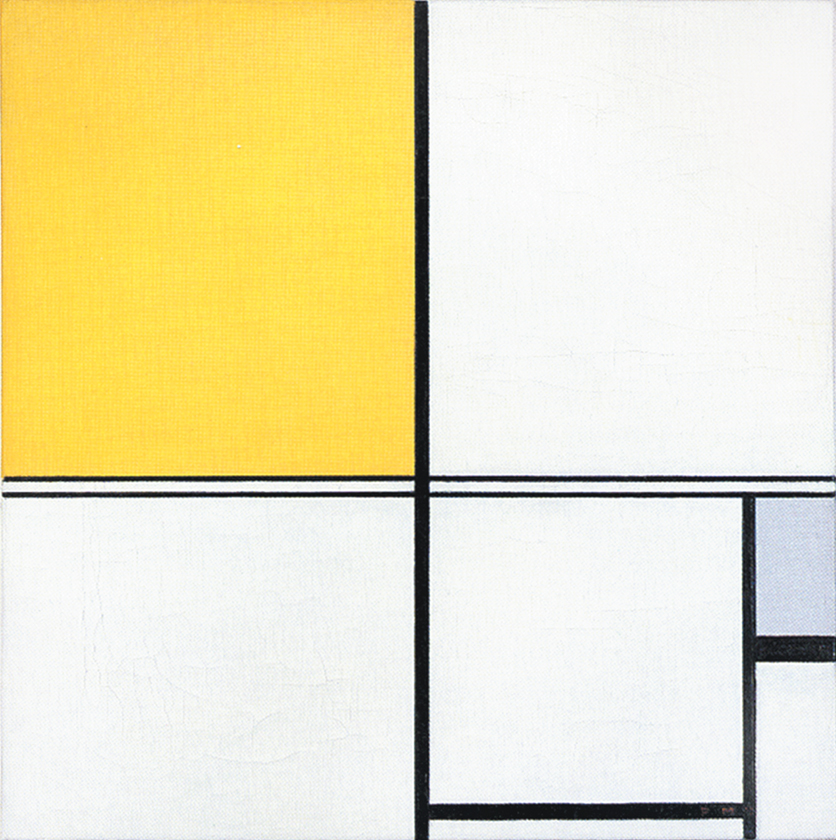

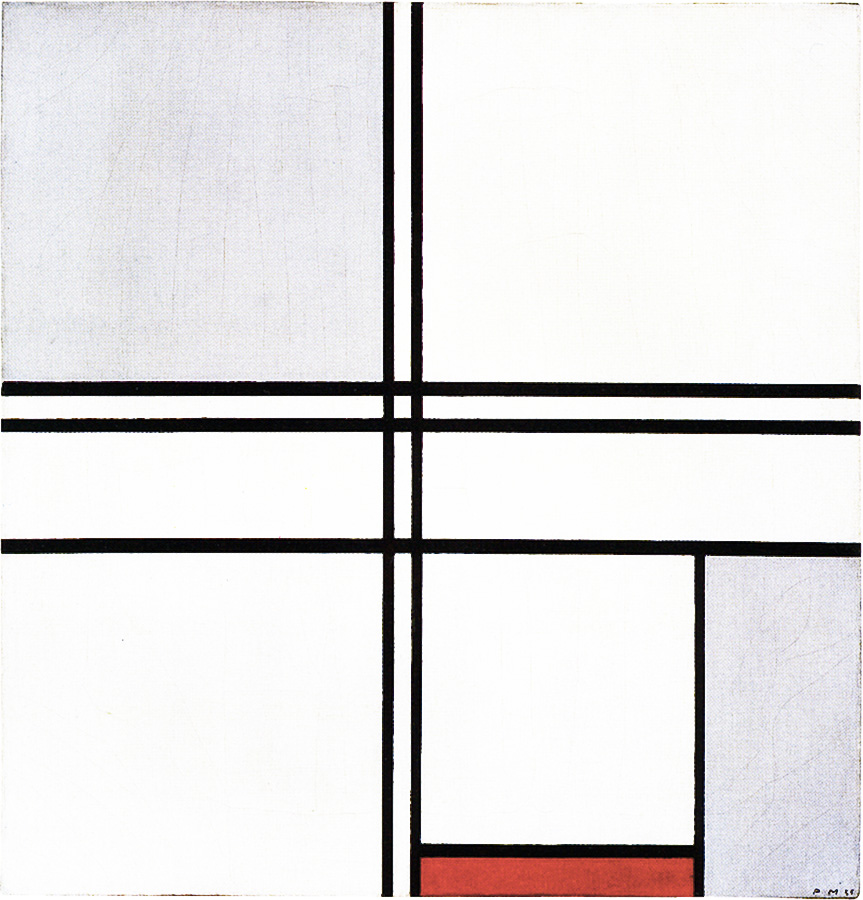

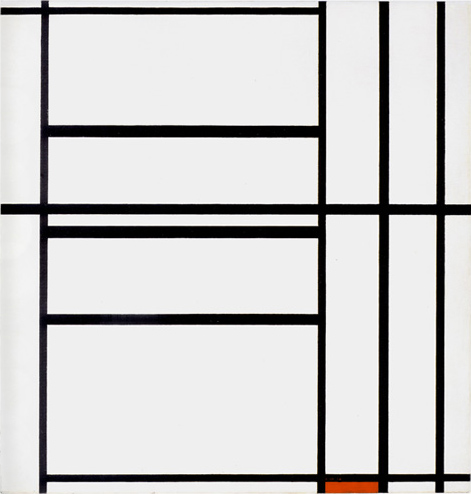

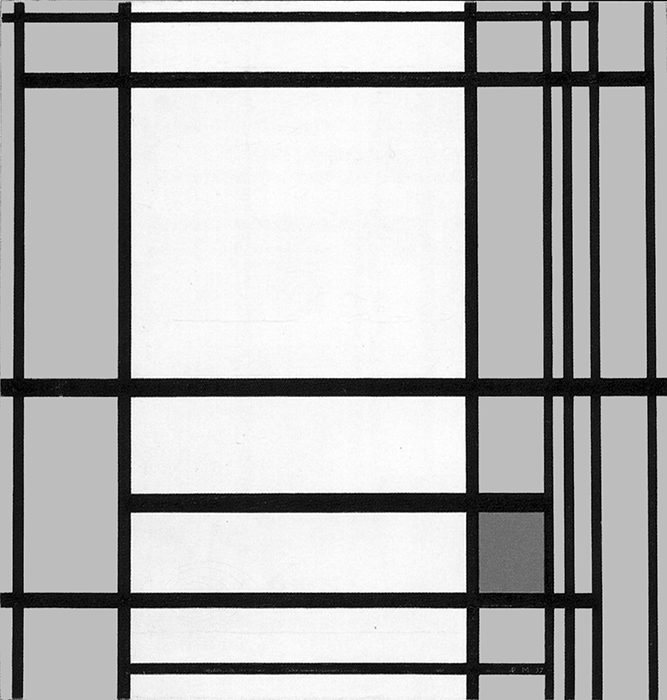

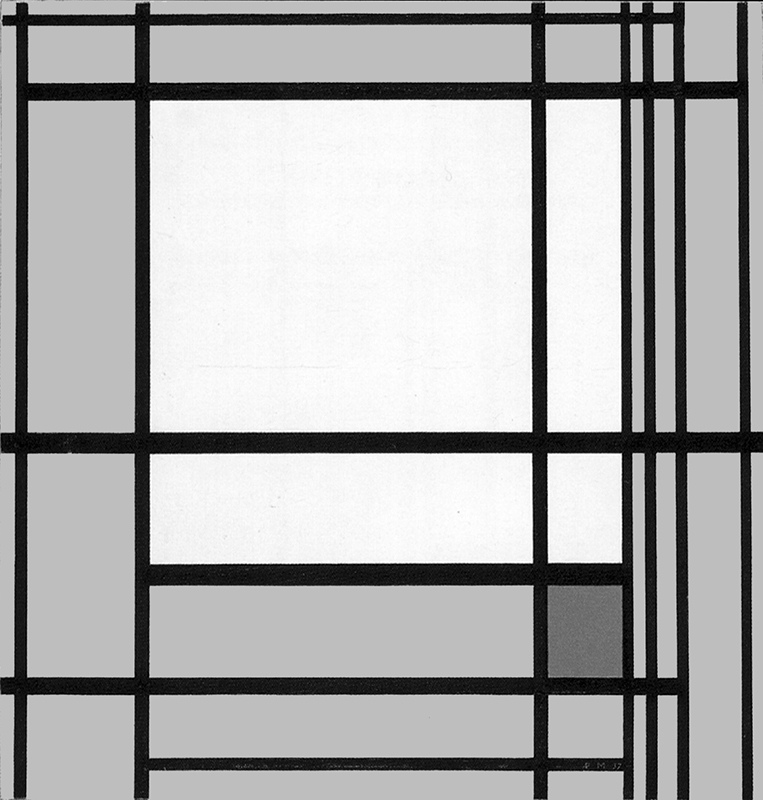

Composition B with Double Line, Yellow and Gray

This is the first Neoplastic composition with two horizontal lines running very close to one another in place of the single horizontal to be seen in all the previous works. The thickness of the two horizontal lines is half that of the vertical:

Composition B with Double Line, Yellow and Gray, 1932, Oil on Canvas, cm. 50 x 50

It is almost as though the two thin black horizontals served to mark out a white line opposing the black no longer solely at the level of form (horizontal or vertical) but also in terms of color (black or white). Black seems ready to open up to white. The small plane on the right is gray, which is an intermediate value between black and white. The yellow plane on the left counterbalances the gray. Yellow was to become the intermediate value between black and white the following year.

Like other compositions based on layout C , Fig. 1 presents an area of square form closed on four sides in the lower right section. The square field expresses a moment of equilibrium between the opposing directions, which elsewhere give birth to variable proportions and then expand in a univocal and absolute way (in exclusively horizontal or vertical terms) and therefore suggesting a virtual infinite space.

The large yellow field in the upper left section and the gray one lower down to the right help to keep the square in a state of unstable equilibrium.

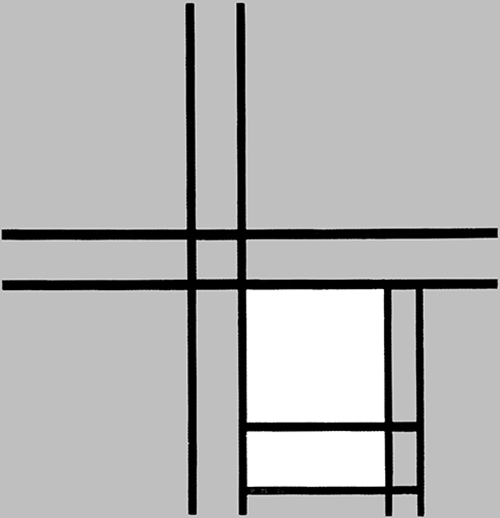

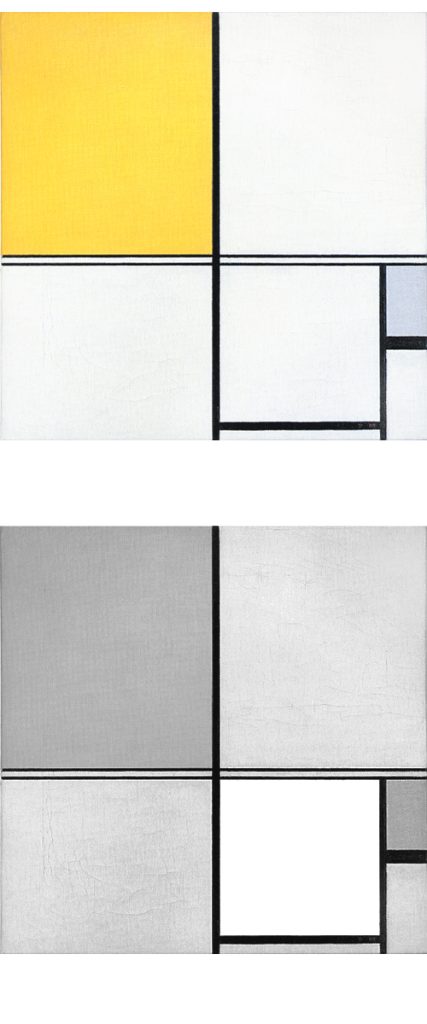

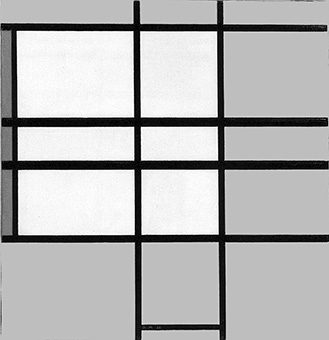

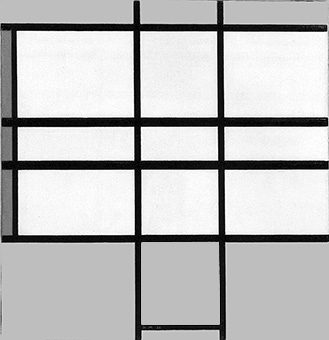

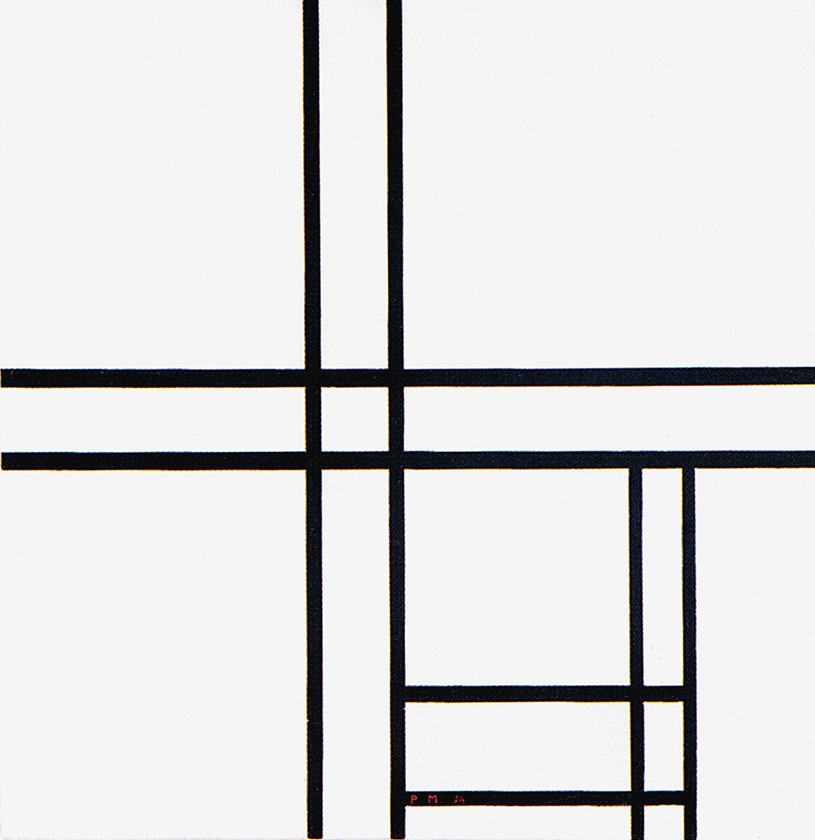

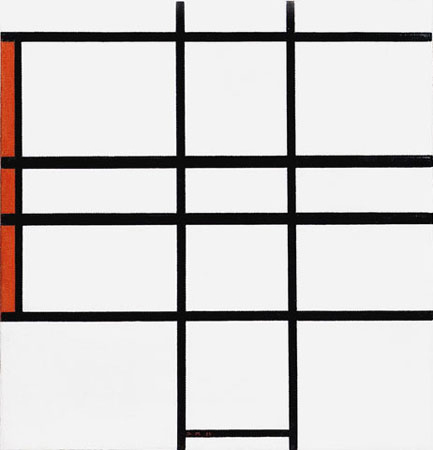

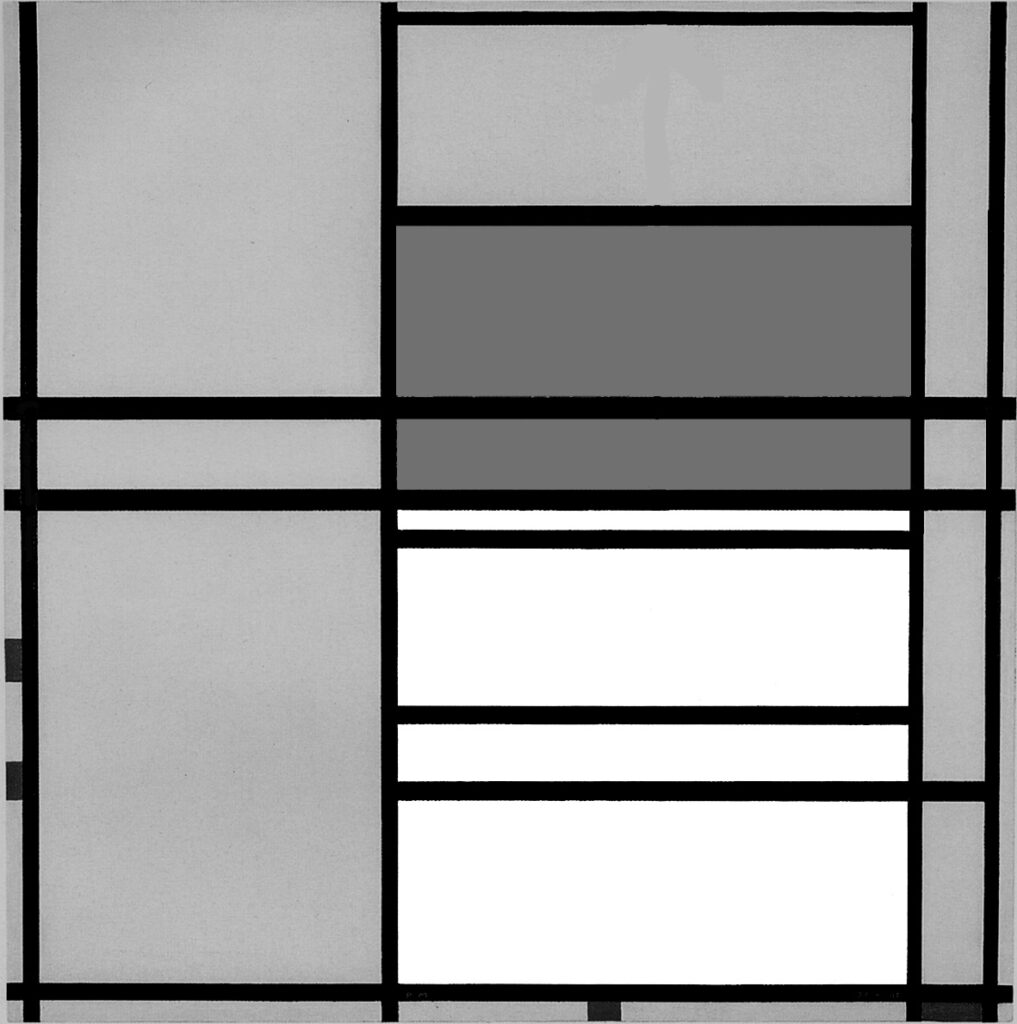

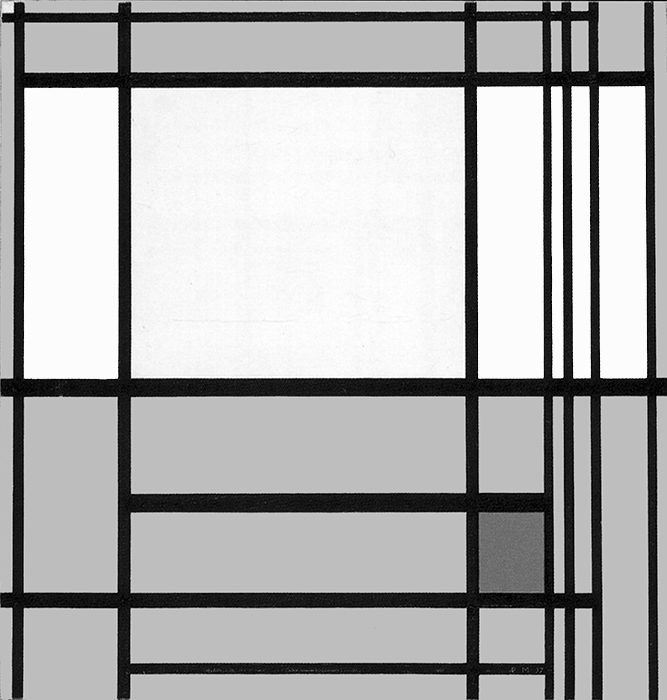

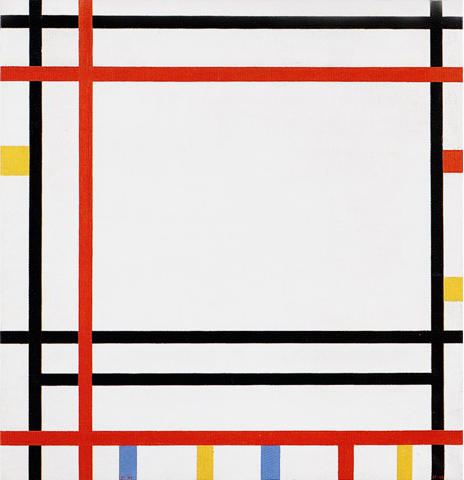

Composition in Black and White with Double Lines

Composition in Black and White with Double Lines, 1934, Oil on Canvas, cm. 59,4 x 60,6

The place of the closed square form seen in Fig.1 is taken in Fig. 2 by a more complex structure made up of two juxtaposed rectangles (Fig. 2 Diagrams A and B) that interact to generate a square form (Fig. 2 Diagram C).

This is a pattern already seen in a composition of 1925:

Same as in 1925, in Fig. 2 the square form, i.e. an equivalence of opposites, appears to be challenged by two opposing forms of predominance, which lends greater dynamism to the square form of the typical layout C.

Fig. 2: Running through the central area are two horizontal lines that seem to be those of Fig. 1 undergoing expansion. The interaction between verticals and horizontals generates a small square (Fig. 2 Diagram C). A relationship is established between a small square of sharply defined and definite size appearing in the center and a larger indefinite square placed in the lower section, which could almost be seen as the smaller one an instant after the lines have passed.

The dynamic movement of these lines drags along the small central square, which opens up while remaining in unstable equilibrium between vertical (Fig. 2 Diagram A) and horizontal (Fig. 2 Diagram B) predominance. Different parts of a Neoplastic composition are to be seen as successive moments of one and the same space undergoing transformation.

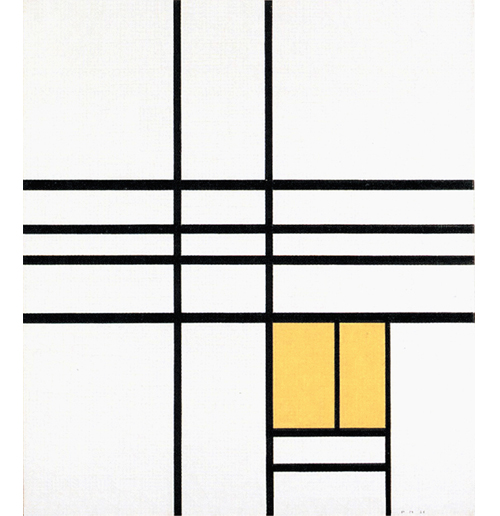

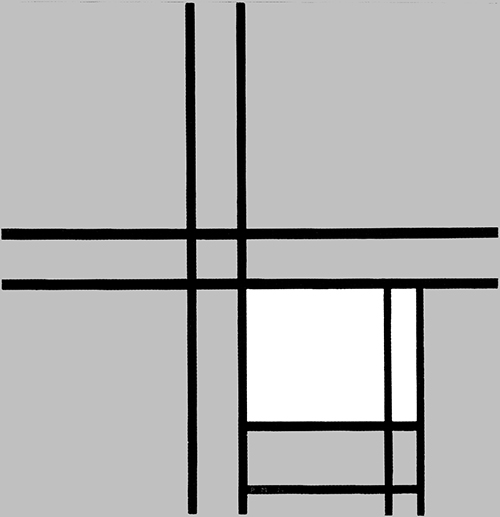

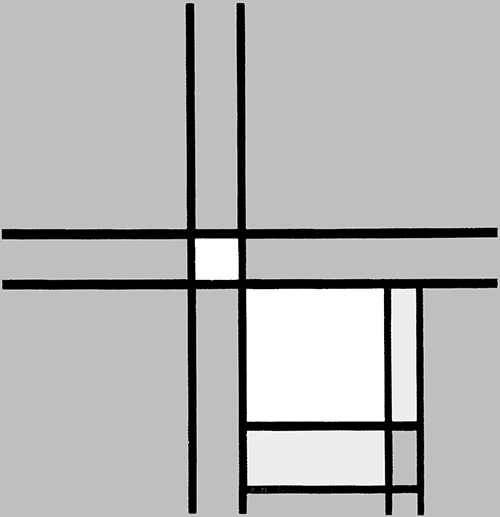

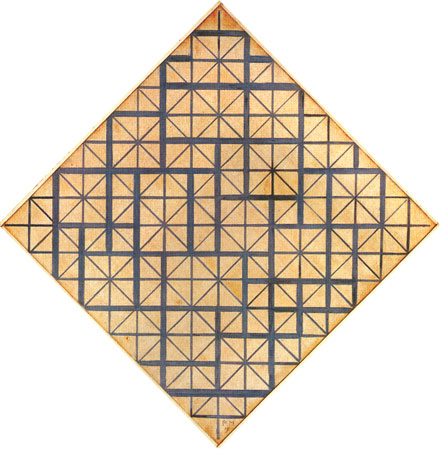

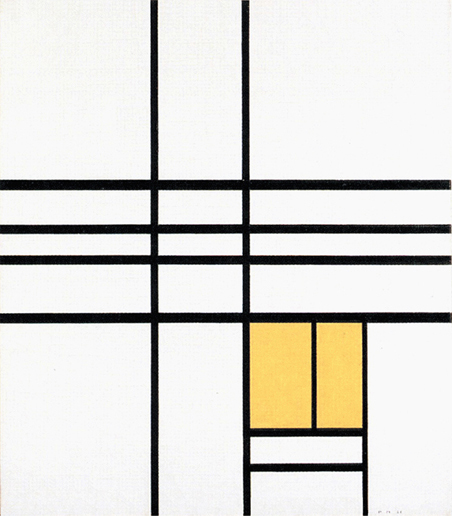

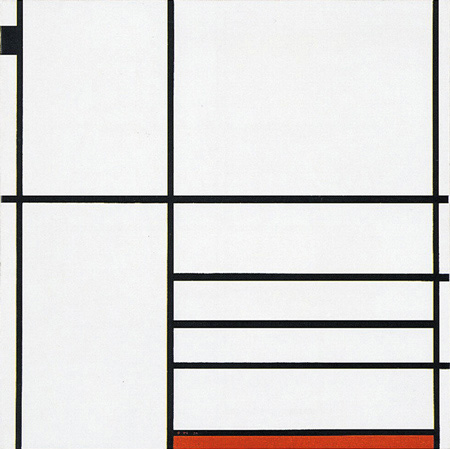

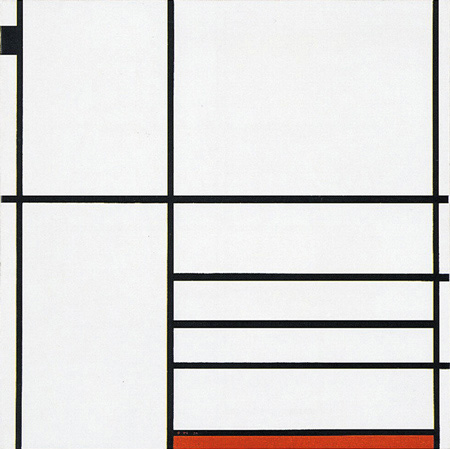

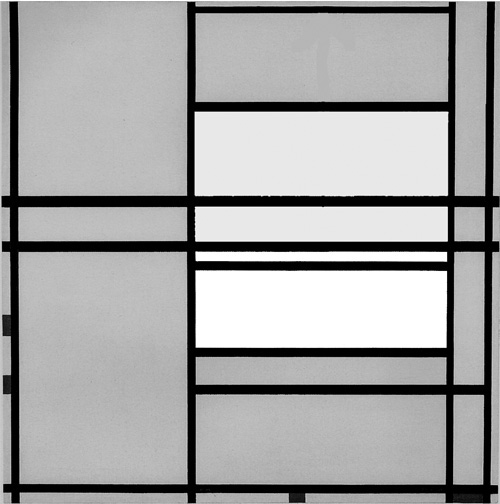

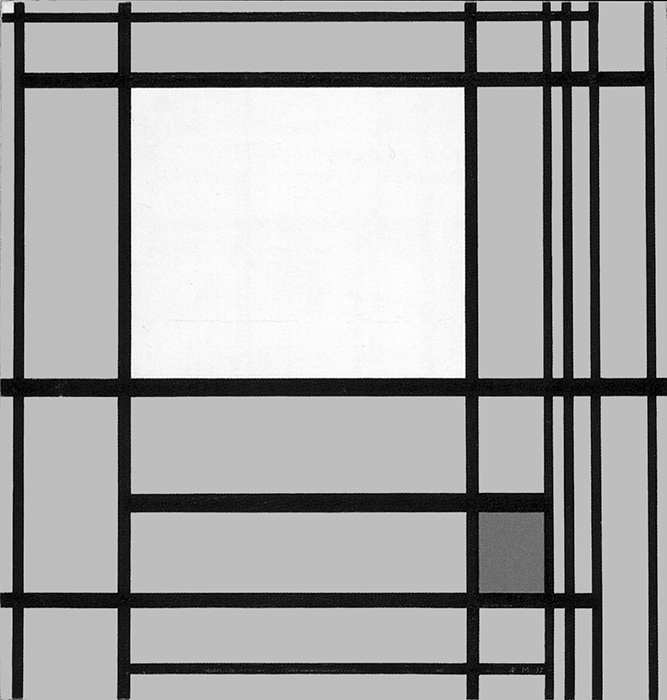

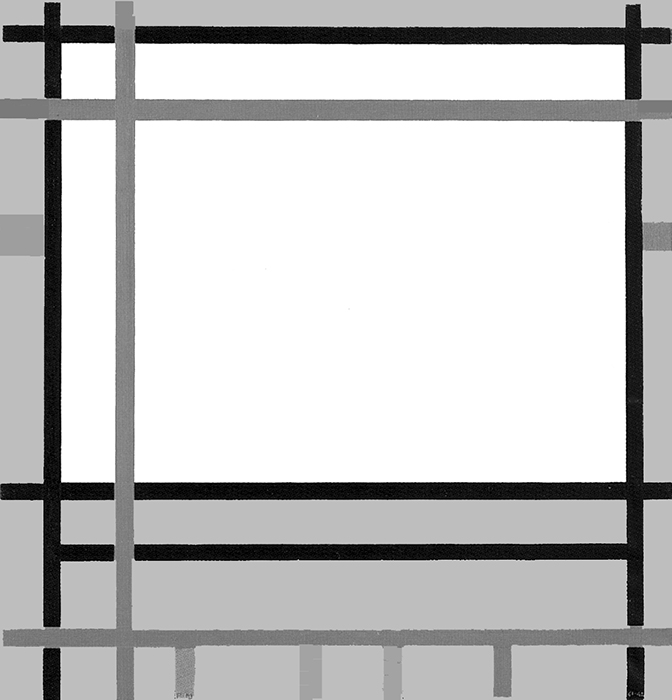

Composition with Yellow

The two horizontal lines running through the central area of Fig. 2 become four in Fig. 3 which is again based on layout C. In this case, however, the field inside the square form is no longer white but yellow and presents a vertical segment echoed by an external horizontal segment in the lower section:

Composition with Yellow, 1936,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 66 x 74

The square form appears in a state of unstable equilibrium between an internal vertical and an external horizontal. I recall Mondrian identifying the vertical with the spiritual whereas the horizontal was a plastic symbol of the natural. Unity (the square form) is in a state of unstable equilibrium between inner and outer worlds. This is the first canvas based on layout C in which the white field of the square accommodates a linear segment, which is another sign of the need to open up the unitary synthesis to manifold space. This linear segment seems designed to indicate the beginning of a process of interpenetration between square and lines.

up to Fig. 4

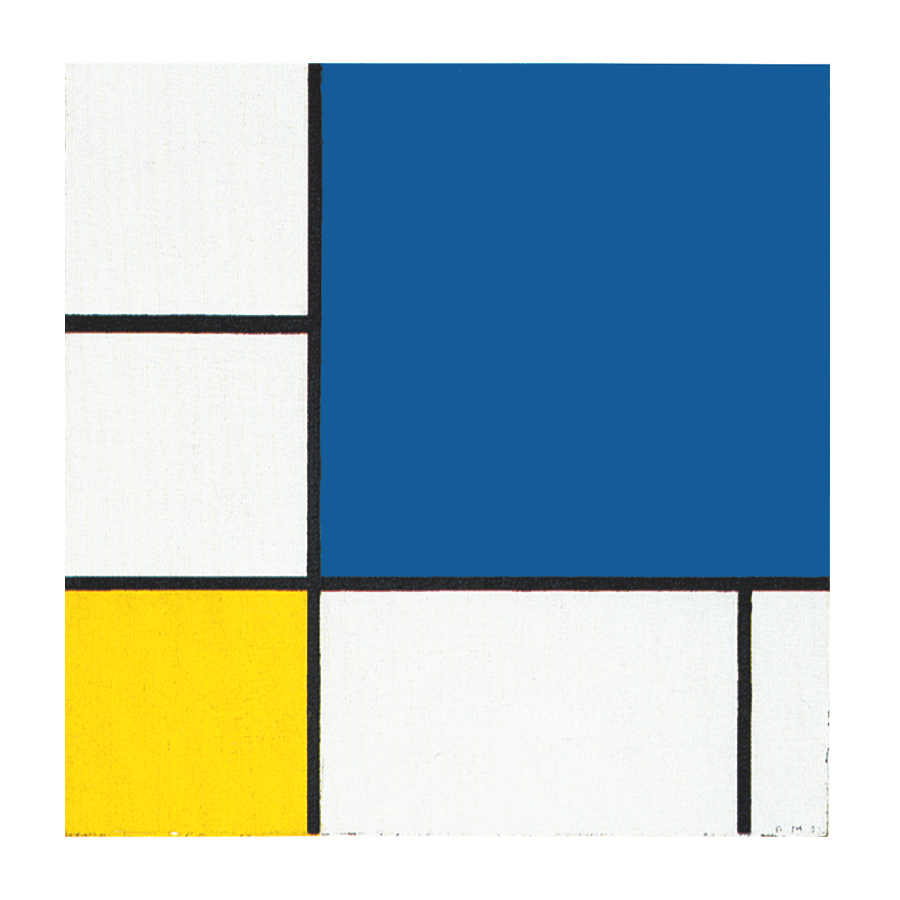

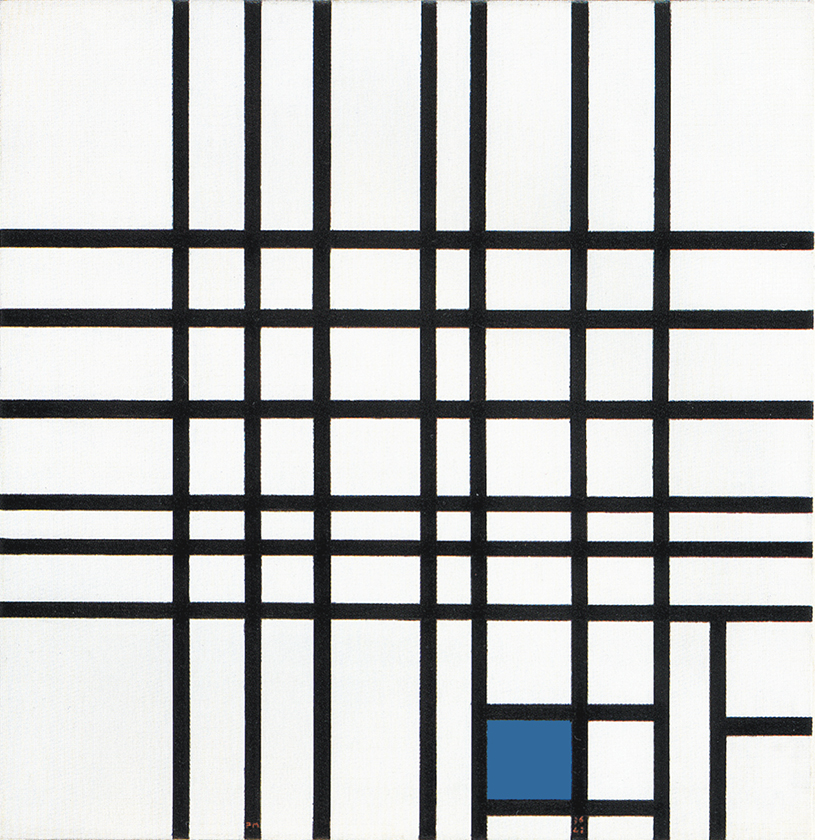

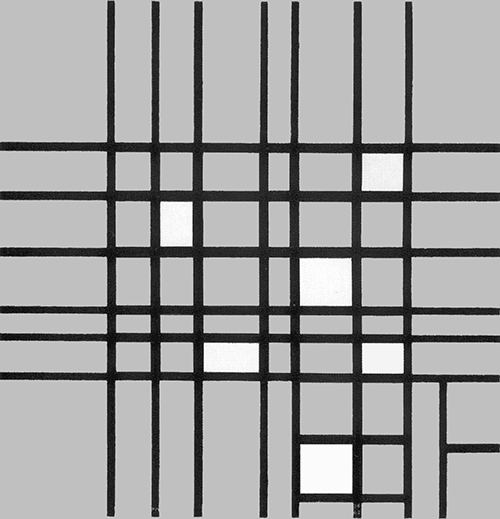

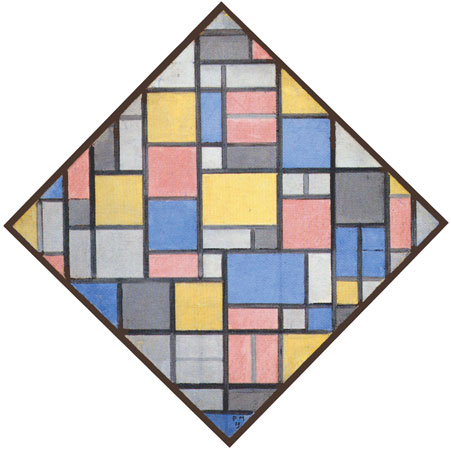

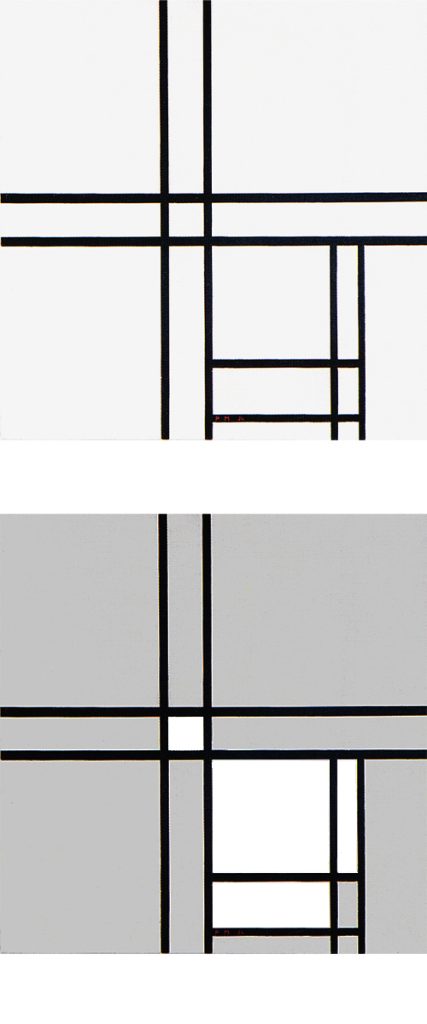

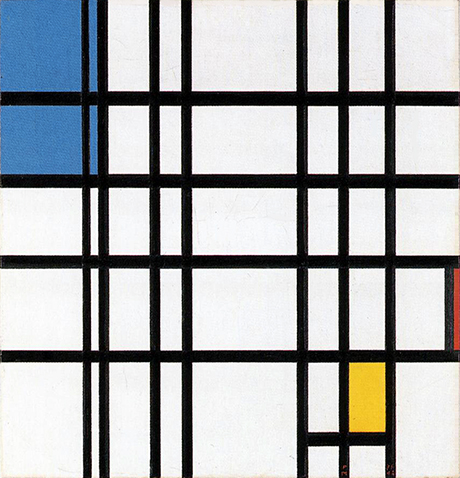

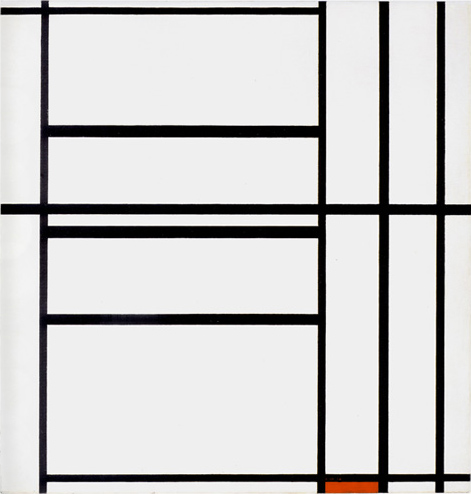

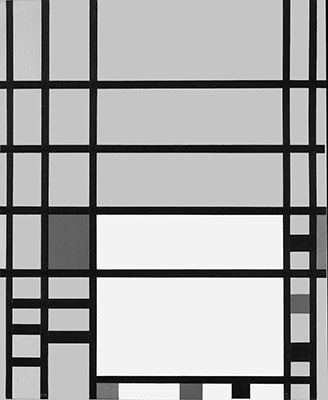

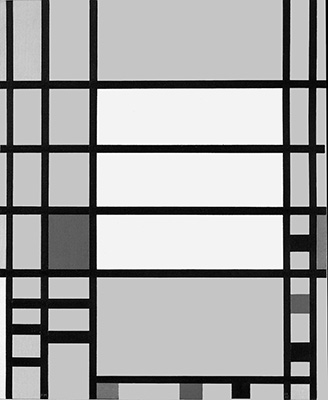

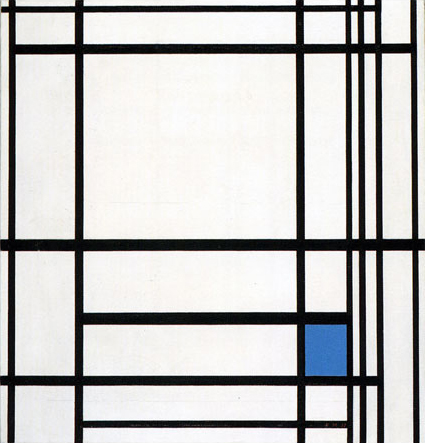

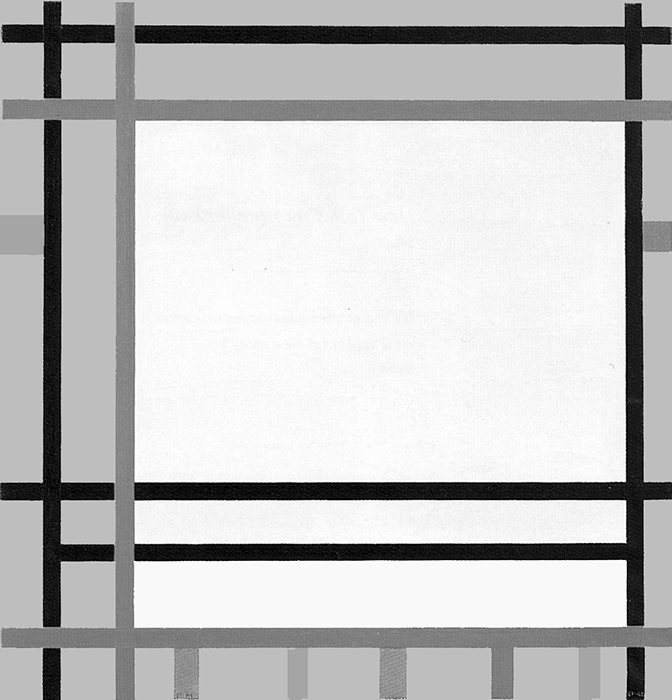

Composition N. 12 with Blue

We have here thirteen perpendicular black lines forming a large number of relations that generate white planes of various shapes and sizes. Areas of greater or lesser horizontal and vertical extension can be seen. Vertical and horizontal attain equivalence in some points for an instant to form smaller or larger squares (Fig. 4 Diagram A):

Space expands and contracts under the pressure of the two contending directions, which attain equivalence and a more stable equilibrium for an instant before opening up again to the more or less marked predominance of one or the other. Equivalences of opposite values are born and dissolve, are lost and found again in forms that are always new.

The idea of the square, i.e. an equivalence of opposites, seems to be expressed here too more as a process than a state. The solid and definite square of the 1920s now appears to undergo dilution on contact with the lines. The latter interact to expand and contract the space, above all in the central area, outside which they become entities in their own right; all horizontals or all verticals, one thing excluding the other. The space becomes absolute and eliminates any possible relationship between the parts.

In the lower right section, the central field flows toward an area of greater synthesis where we can pause to observe a smaller number of planes (Fig. 4 Diagram B):

One of a bright blue color appears as the fourth part of a larger form that recalls the square of the layout C by virtue of the position it occupies.

We move from an area of extremely variable space (the central field), where equivalence appears in a state of becoming, to one in which the space is more constant (the smaller field) and then to a more stable synthesis of opposite values high-lighted by color. The accent of color seems designed to draw attention to a square, which appears as a sort of model of which the planes observed in the central area constitute a variation:

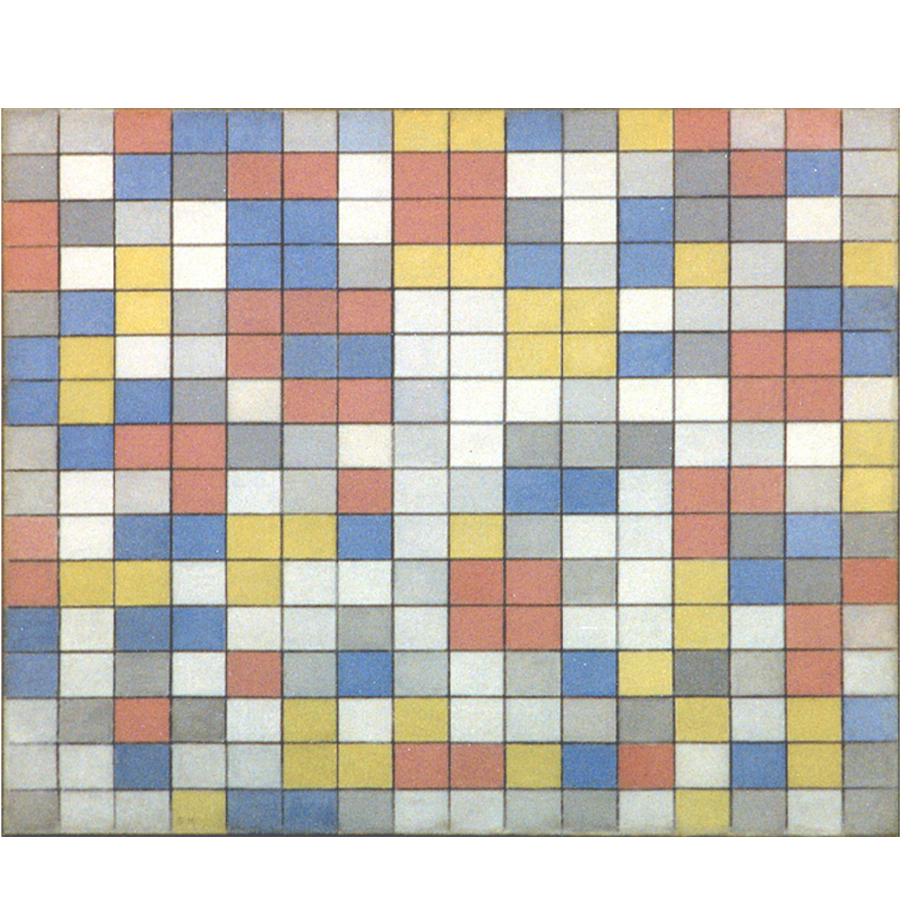

I recall the compositions of 1919 in which all the measures and the proportions varied on the basis of a constant module. Now there is no longer any prior control:

Composition N. 12 with Blue (Fig. 4) appears to offer a summary of all the compositions that Mondrian produced between 1929 and 1932 involving variations on the theme of the square:

such as for instance Composition with Yellow, with a closed square, an area of slightly greater horizontal development (lower left), a shape of greater vertical development (upper right) and one of less greater development (upper left) or Composition with Blue and Yellow with a large blue square, a smaller yellow square and two white similar squares. A whole variety of attempts to reach an equivalences of opposites. We seem to see all these different proportions brought together in Composition 12 with Blue (Fig. 4).

In the course of the 1930s we move from a sharply defined and definite square (Fig. 1) placed in a state of dynamic equilibrium (Fig. 2) and finally a multiple variation of the square module in a state of becoming that has undergone total interpenetration with the lines and is expressed as a continuing variation on itself (Fig. 4):

Observation of the three works in sequential order reveals how the “white line” running through the center of Fig. 1 leads through Fig. 2 to the multiplicity of Fig. 4. Since 1919 and throughout the 1920’s white had been the color Mondrian often used for the square field, that is to say, to express unity. White (the space within the double black line of Fig. 1) opens up now to complexity (Fig. 2 and 4) which is tantamount to say that unity opens up to multiplicity.

In 1937 Mondrian published an important essay entitled “Plastic Art and Pure Plastic Art”. Interest in his work increased steadily in England, but especially in the United States, among both collectors and fellow-artists.

In January 1938 he wrote to Harry Holtzman that he had in mind the project for a modern school of aesthetics that, as an alternative to the New Bauhaus in Chicago, would promote a new teaching of art, architecture and industry.

Hoping to overcome his recurring sense of weakness and frequent respiratory infections, Mondrian adopted a vegetarian and salt-free diet.

Michel Seuphor, Piet Mondrian, Sa Vie, son Oeuvre, 1956

It appears to be a short step from Composition N. 12 with Blue to New York City:

In actual fact, however, the process of spatial multiplication was not completed so quickly. It was a laborious undertaking that took seven years of patient effort and a far larger number of works. Mondrian produced no fewer than sixty-five canvases between 1932 and 1942, some of which were reworked in New York after 1942 while about a dozen were left unfinished. While aiming at increasing the elements forming these new compositions, the artist adopted several solutions leading ultimately to the same result which is to depict on a bi-dimensional space the infinite multiplicity of the world considered as a unit and see unity as a complexity of parts.

Mondrian: “The one seems to us to be only one, but is in actual fact also a duality. Each thing again displays the whole on a small scale. The microcosm is equal as composition to the macrocosm, according to the wise. We therefore have only to consider everything in itself, the one as a complex. Conversely, every element of a complex is to be seen as a part of a whole. Then we will always see the relationship; then we can always know the one through the other.“

The common denominator of Mondrian’s oeuvre as a whole is in fact the need for unity and at the same type the opening up and multiplication of unity. During this phase we see the opening up and multiplication of unity in all the works produced between 1932 and 1942, but the progress achieved was very slow. There were phases of uncertainty with works begun but never completed or taken up later and altered.

In 1936 Mondrian lived in a much less spacious studio on the second floor on the courtyard, boulevard Raspail in a plush-looking building. It was there, in this studio that he did not like, to which he did not seem to be able to get used, that the sounds of war came to haunt his mind. Fascist Italy, Hitler’s Germany, Franco’s Spain were becoming more and more threatening. France seemed to be surrounded. After Munich, Mondrian saw war imminent.

Knowing that Paris would be destroyed, an easy target for German planes, he announced his arrival to Nicholson and Gabo, and left for London, with no thought of returning, on September 21, 1938. “I’m on my way to America,” he said upon arrival. But he felt very well in London and in the studio room that Gabo and Nicholson had found for him, opposite their studios in Hampstaed, he immediately began to work.

Settled in London, in the month of October of the 1938 Mondrian arranged the shipment of the paintings of greater dimensions, the gramophone, twelve discs and one case of manuscripts. He often hosted his friends for dinner and even sold some of his paintings. With Mrs. Gabo’s help, he bought bare wood furniture from a wholesale dealer and painted it white.

Michel Seuphor, Piet Mondrian, Sa Vie, son Oeuvre, 1956

Neoplasticism evolves through new works

The evolution of Neoplasticism toward articulation and complexity continues with new compositions Mondrian works at between 1934 and 1942. These can be grouped into three basic groups.

We have just examined the first group of works which shows a multiplication and diversification of the square into a variety of slightly more horizontal or vertical proportion which are in some cases highlighted by colors:

We shall now examine a second group of works which present a square form interpenetrating with a vertical field that runs through the whole composition from the bottom to the top. The vertical field seems to originate from the double vertical lines of the first composition:

The third group of works reveals the need to maintain the visibility of a large square generated by the combination of various proportions that interact with one another to evoke moments of equilibrium inside a space that changes constantly in appearance:

The common denominator of all these new works is to see the equivalence of opposites (the square proportion) interpenetrate with the dynamic and ever-changing flow of the lines and the rectangles generated by them; to show the equivalence of opposites merge into all possible imbalances.

After the extreme synthesis of 1933, the painter reopens the square proportion and with it the entire composition to an increasing level of multiplicity.

Let us observe some of these works.

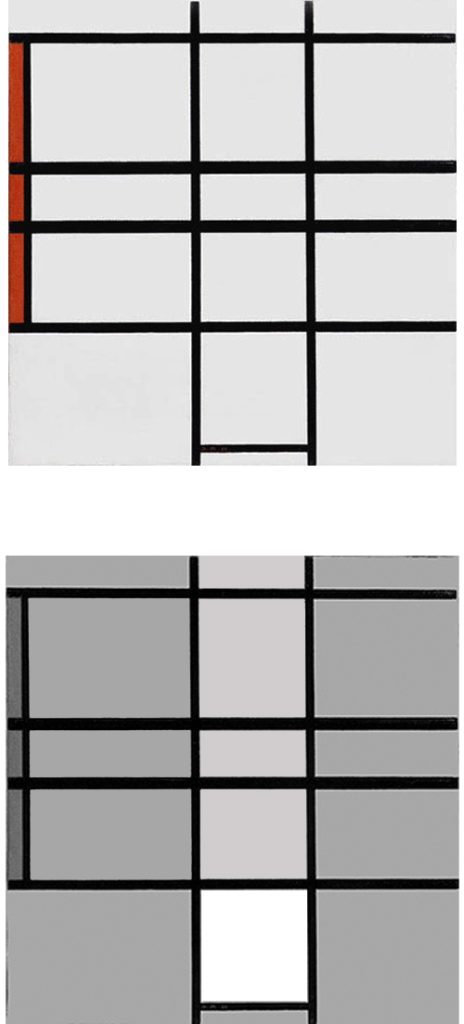

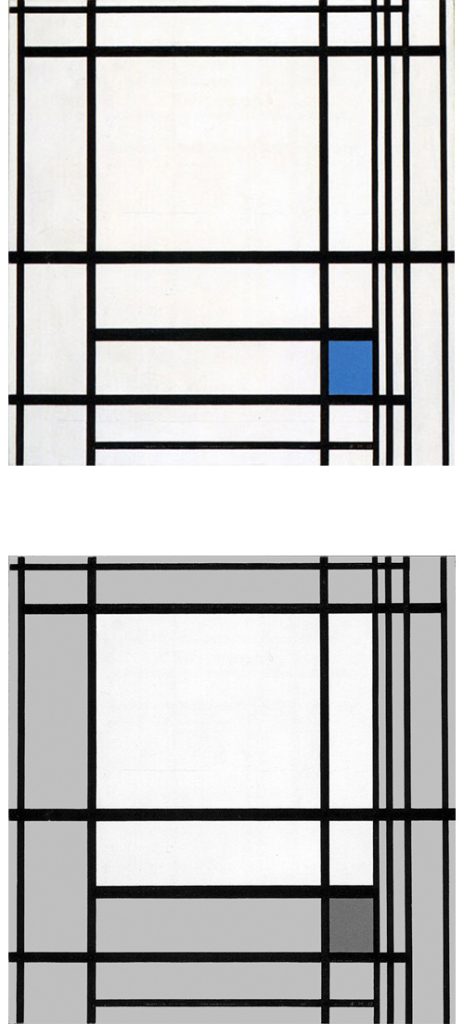

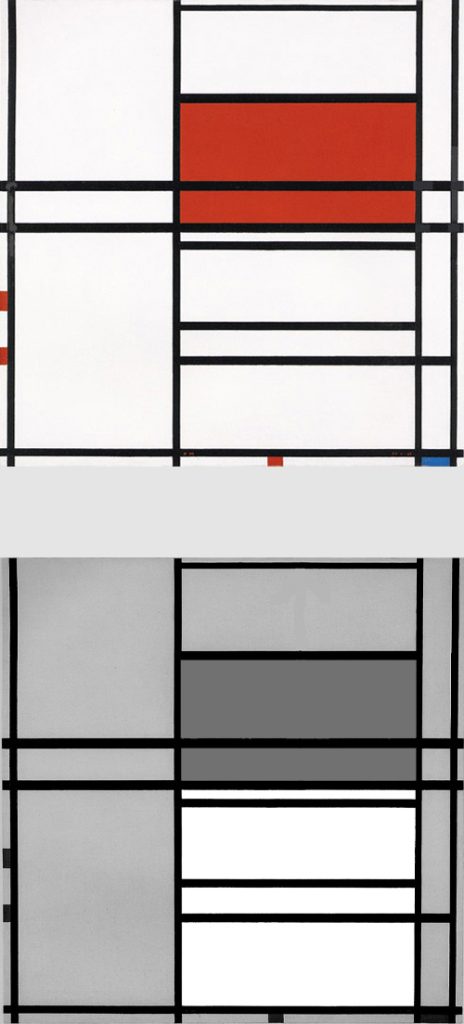

Composition N. I Gris Rouge

Two perpendicular lines seem intent on pulling the square unit toward the upper section and the left, while the accent of color exerts a pull to the right.

Same as in other works of this type the composition is in dynamic equilibrium between a space expanding to a virtually infinite space (the opposite lines) and the same space momentarily concentrated in a finite relationship (the square proportion):

Composition Gris Rouge, 1935,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 55 x 56,9

The three areas that remain open seem designed to express possible variants of the square that remains closed. The horizontal predominates slightly in one case and the vertical in another. The impression is sometimes of a square, but the differences are minimal. These planes express a variable space in relation to the square, in which the opposite values attain definite equivalence.

Composition Blanc et Rouge B

The red plane gives the vertical measurement of a field generated by four horizontal lines contending for the space with the two verticals running throughout the centre of the canvas.

An approximate square at the bottom moves upward along the two vertical lines and merges with the four horizontal lines:

Composition Blanc et Rouge B,

1936, Oil on Canvas, cm. 50,5 x 51,5

Fig. 6 Diagram A: Through this interaction the square (1) assumes horizontal proportions (2) that are accentuated (3 and 4) before regaining vertical development (5) and open up again to an horizontal prevalence (6). The initial square form displays now a variety of possible relations between the opposites: Unity manifests itself as an ever-changing multiplicity:

Fig. 6 Diagram A: Areas marked 2, 3, 5, 6 form a new and larger square (Fig. 6 Diagram B):

The smaller approximate square (at the bottom Fig. 6 Diagram A – Area 1) seems to turn into the larger one (Fig. 6 Diagram B), as though the two forms were successive moments in the transition of the same entity from a state of comparative stability and certainty (the small compact square) to a dynamic condition of less stability and multiplicity (the large manifold square).

The large composite square (Fig. 6 Diagram B) then opens up again to an infinite space of the endless lines and is lost (Fig. 6 Diagram C):

In Fig. 6 we are confronted with a geometry of becoming.

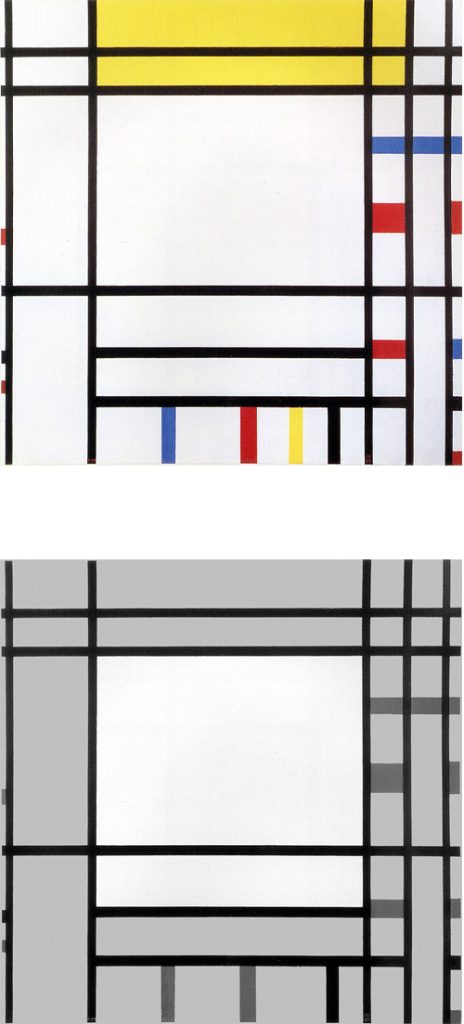

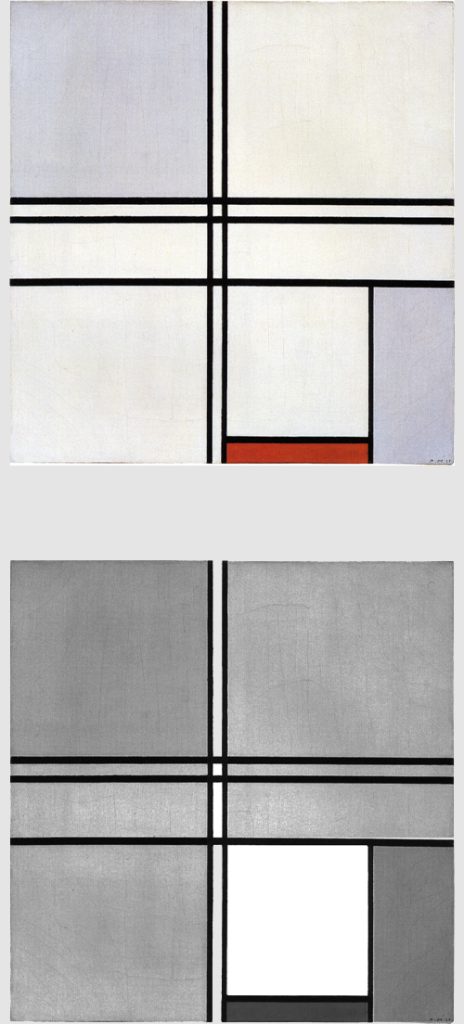

Composition in White, Black and Red

The tendency to open up, divide and making more dynamic the equivalence of opposites (the square form) takes shape here:

Composition in White, Black and Red, 1936,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 102 x 104

The lines work in fact to divide the space of the canvas into four large areas of different proportions. Only one of these, underscored by a red plane, is closed on four sides and approaches the proportions of a square. This square is larger than what is normally seen in the compositional Layout C.

While the homogeneous square field of Fig. 5 opens up to a vertical segment in Fig. 3, it increases in size and opens up to three horizontal segments that divide its inner field and make it less stable in Fig. 7. The central segment is wholly included in the square form while the other two extend outside toward the right. A black accent in the upper left section counterbalances the weight of the segments and the red plane.

Composition N. 4 with Red and Blue

Fig. 7 was produced in 1936 and Fig. 8 in 1938, implemented with some color accents in 1942.

Composition in White, Black and Red, 1936, Oil on Canvas, cm 102 x 104

Composition N. 4 with Red and Blue, 1938-42, Oil on Canvas, cm. 99,1 x 103

Comparison of the two canvases reveals that the square area of the first canvas continues upward in the second:

Diagram A

Diagram B

Diagram C

The large square of Fig. 7 thus becomes a dynamic vertical sequence in Fig. 8 where the vertical field is marked by horizontal segments that generate a series of rectangles, one of which is red. By combining these rectangles, we can glimpse square forms taking shape, merging with red and then dissolving toward the top.

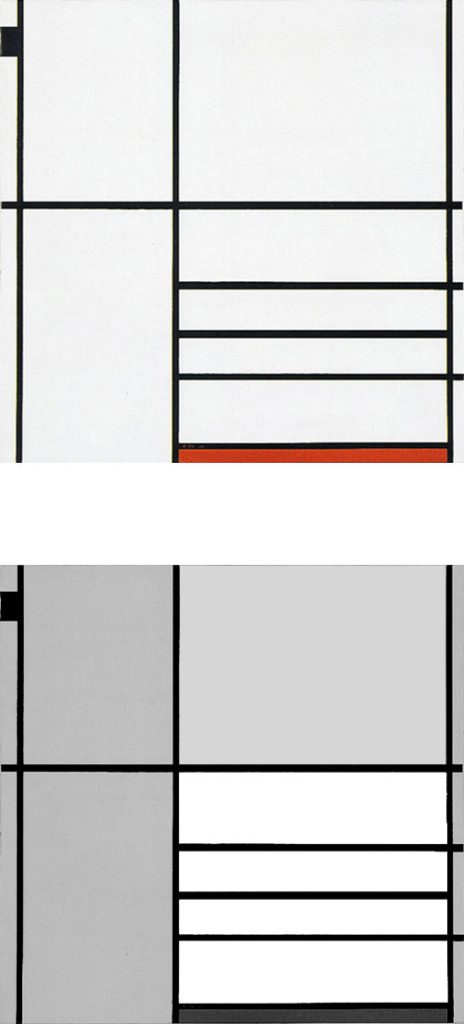

Composition N. 1 with Red

This composition presents an analogous development to Fig. 8 with a vertical field marked out by horizontal rectangular sections.

With respect to the layout of the previous canvas, the vertical field made up of horizontal rectangles is here shifted to the left.

Composition N. 1 with Red, 1938-39,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 102,3 x 105,2

The marked presence of vertical lines on the right prompts a vertical reading of the horizontal sections inside the vertical field. On observing these sections, we note that their vertical component gradually decreases little by little as we move up from the bottom toward the horizontal line running through the middle of the composition, the only uninterrupted horizontal line present in this work. The other horizontals are in fact three segments set between the vertical lines and two in the lower and upper part that continue outside to the right and left respectively.

Diagram A

Diagram B

Diagram C

Reading from the bottom toward the center of the canvas, we thus see a decrease in the vertical component of each horizontal section. The vertical/horizontal space becomes almost entirely horizontal (Diagram A). During this process it is possible to intuit a square form (Diagram B).

The horizontal rectangles contract in the center to assume the proportions of a very narrow white plane (Diagram A) that has practically the same thickness as the black segment and the line defining it. The narrow plane has in fact the appearance of a white linear segment. Planes and lines (finite space and infinite space) as well as black and white are equivalent in this area.

While the space becomes almost exclusively horizontal proceeding from the bottom edge toward the center, the vertical component shows an increase as we move from the center towards the upper part of the canvas (Diagram C).

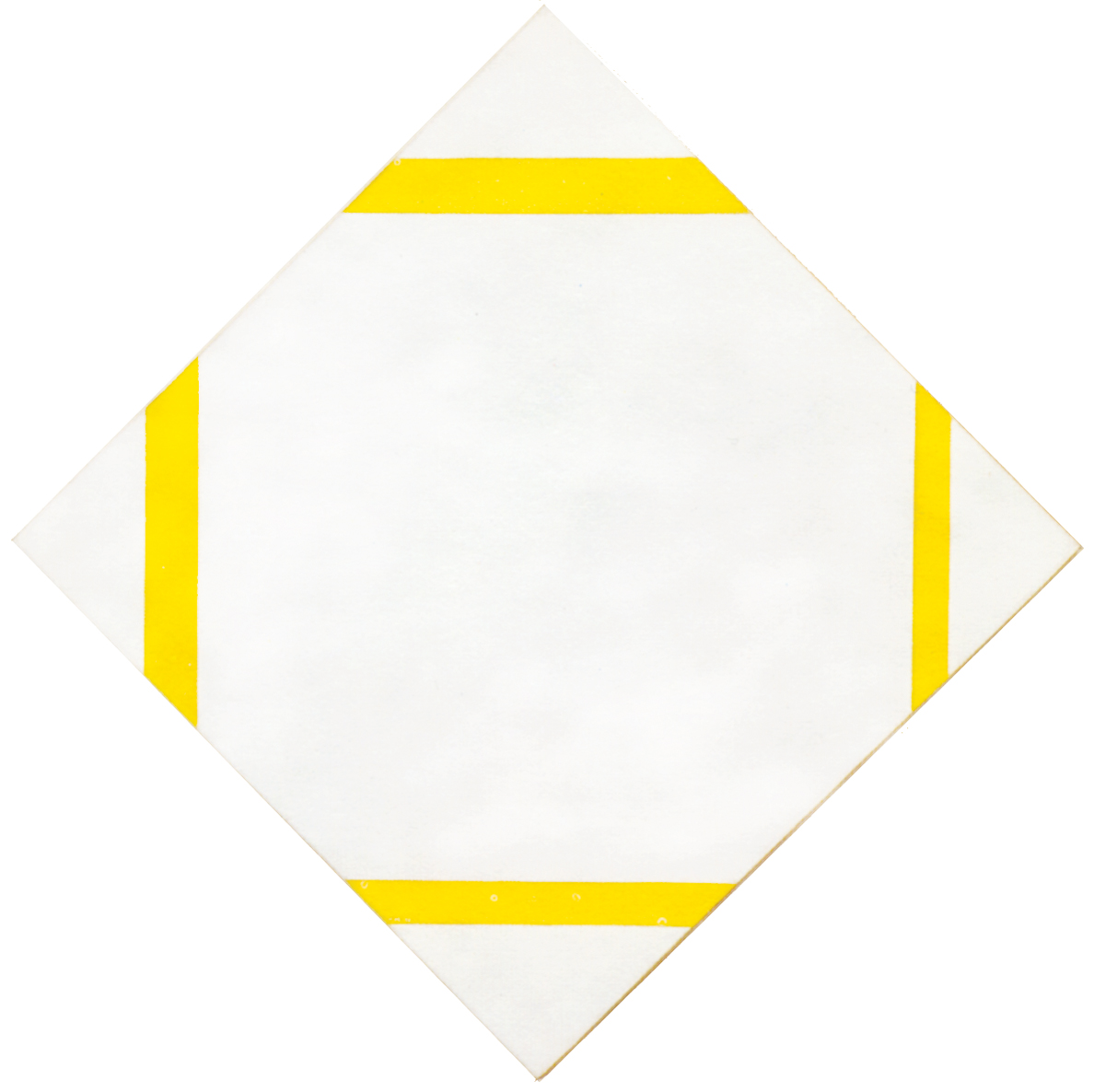

It is no coincidence that we see an equivalence of opposite values generated in the center of the canvas. Six years earlier Lozenge with Yellow Lines shows an increase in the thickness of the lines seemed to suggest their evolution toward potential planes while, in terms of color, yellow was used as an intermediate value between black and white.

Observe the contrast between the only horizontal line and the black segment beneath it. The latter appears slightly thicker as though the black horizontal line became the segment for an instant and the loss of extension were transformed into an increase in thickness:

Composition N. 1 with Red, 1938-39

The concomitance of the line and the segment produces a space simultaneously undergoing expansion and concentration. A measured red accent draws the eye toward the lower section and works together with the vertical lines on the right to reopen the space gradually accumulated toward the center. We are thus once again immersed in a vertical movement that gradually tends to become horizontal before reverting to vertical expansion. The red counterbalances and reopens the center, where black and white attain dynamic equivalence for an instant.

Trafalgar Square

Fig. 10 follows the same layout as the three works we have just examined with a vertical development of horizontal sections which suggest an open and dynamic square form (Fig. 10 Diagrams A, B, C):

Trafalgar Square, 1939-43,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 120 x 145,2

Diagram A

Diagram B

Diagram C

It should be borne in mind, however, that the composition was drafted in 1939 and the small accents of color present in the lower and right sections were added in 1942-43. The additions strike me as no improvement and indeed as spurious interference with the initial composition.

Mondrian named some works from this latter period after squares in cities where he had lived: London with Trafalgar Square, in another case Paris with a canvas named Place de la Concorde and finally New York City with the name of an avenue Broadway Boogie Woogie. Unfortunately, these titles have produced misleading interpretations.

The bombings in London put Mondrian’s nerves to the test. When he had been in New York for more than a year, he still felt the nervous shock of the bombings when a siren from some boat on the East River reminded him of the warning signal that sometimes barely preceded the fall of the machines. In spite of the isolation, the precarious life and the constant air attacks, he still hesitated to answer Harry Holtzman’s call.

Holtzman was only able to convince him with the news – which was not true – that the British government itself was about to reach Canada. Only then did Mondrian accept the ticket.

He took the boat at the end of September 1940 and arrived in New York on October 3. “He was very tired and weakened by the dangers and difficulties he had experienced,” writes Holtzman, “but with rest, good food and care, he soon recovered.”

Michel Seuphor, Piet Mondrian, Sa Vie, son Oeuvre, 1956

As mentioned, during this period Mondrian worked at some paintings which again present a large square generated in the central area of the composition:

Let us examine these works:

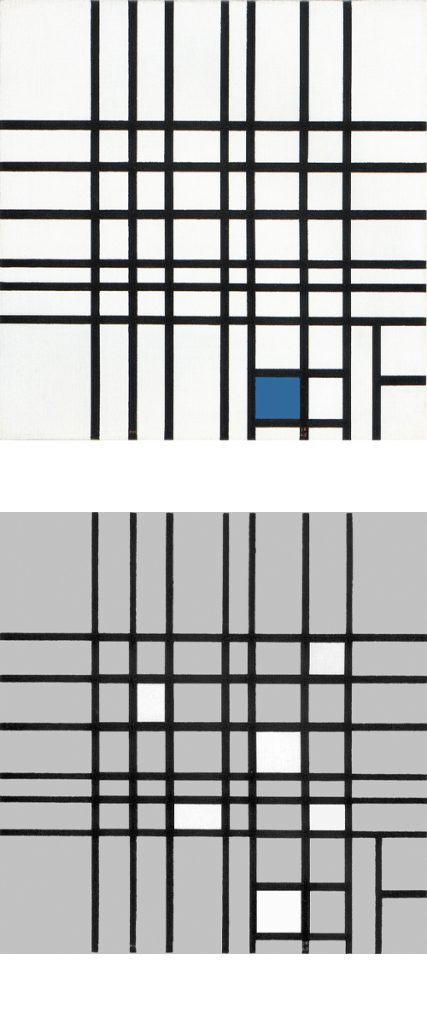

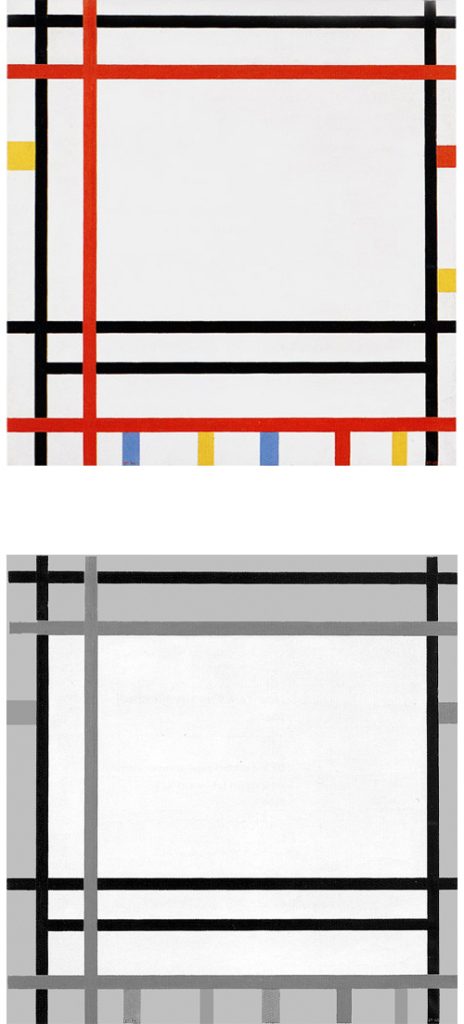

Composition des Lignes e Couleur III

Seven vertical lines meet one horizontal line and five horizontal linear segments.

Three vertical lines run very close to one another on the right and the white areas formed between them are rectilinear planes; some of them seem intent on turning into white linear segments:

Composition des Lignes e Couleur III, 1937,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 77 x 80

We again see here a vertical field that proceeds from the bottom through the central area of the composition to the top (Fig. 11 Diagram A). The vertical field is counterbalanced by a horizontal field in the upper area of the composition (Fig. 11 Diagram B). The intersection of the two opposite fields generate an area close to a square (Fig. 11 Diagram C):

Diagram A

Diagram B

Diagram C

Diagram D

A small blue plane concentrates the space in the lower right section and draws attention to a larger form which suggests for an instant a large square field (Fig. 11 Diagram D). The central approximate square (Diagram C) shows a slight horizontal expansion while the large square (Diagram D) a slightly vertical predominance. Between the two we intuit a probable square, that is, a dynamic equivalence of opposites. The space is thus opened up again to new measurements and proportions of a variable nature that attain equivalence every so often before overbalancing in one direction or the other.

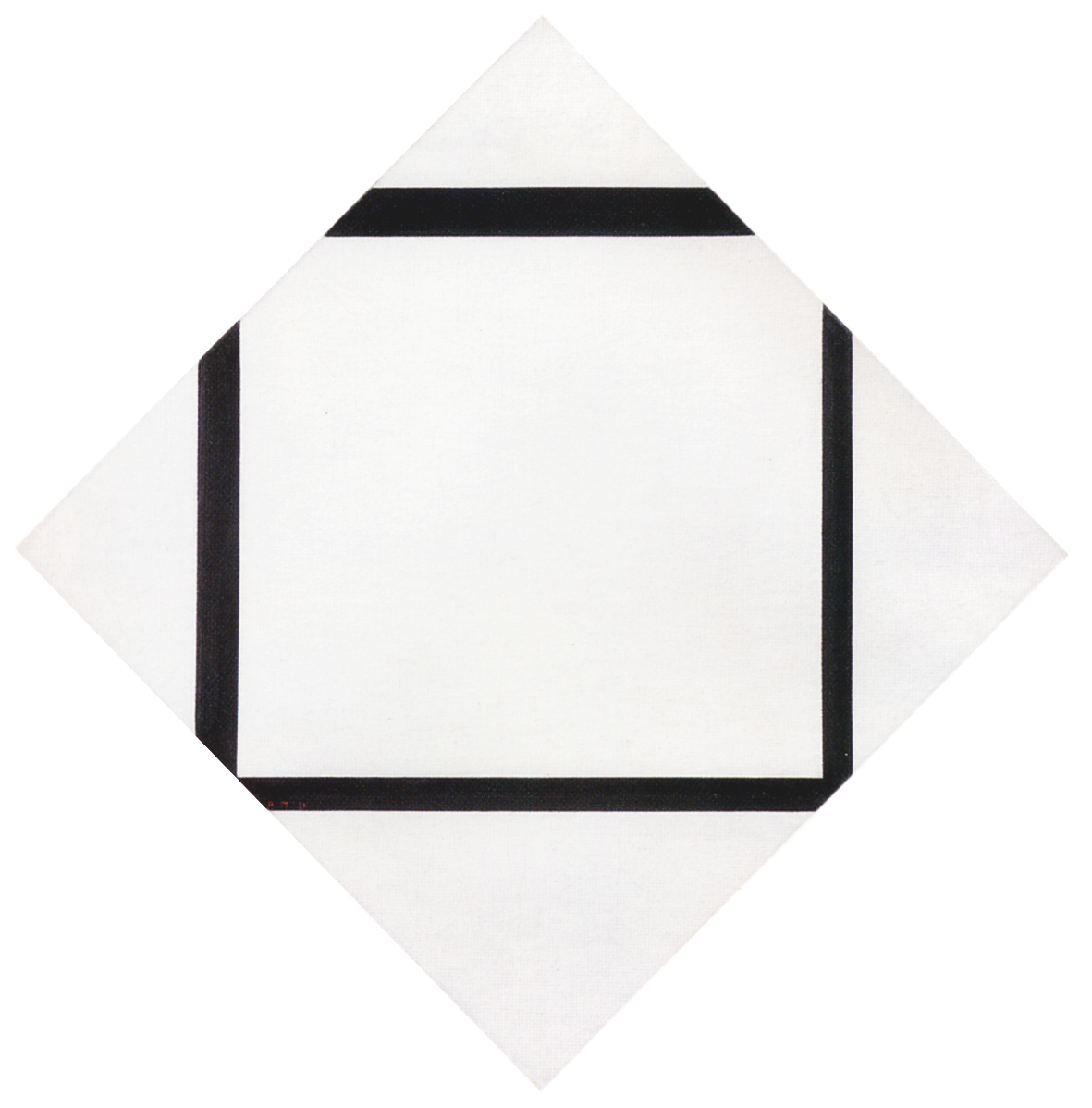

Lozenge Composition with Eight Lines and Red

Eight lines, differing in extension and thickness, suggest a dynamic, slightly more horizontal square field expanding toward the left while a red accent draws our attention towards the right:

Lozenge Composition with Eight Lines and Red, 1938, Oil on Canvas, cm. 100 x 100

Compared with the earlier lozenge compositions, in Fig. 12 the square unit consists of a larger and diversified amount of elements. This is also a way to open up unity to multiplicity.

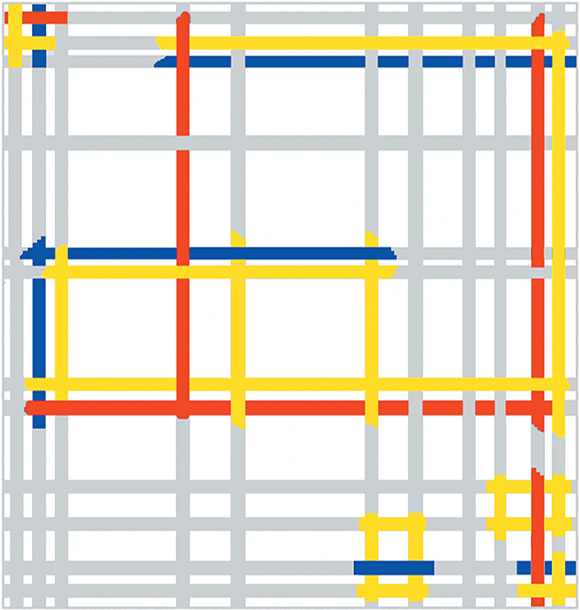

New York Boogie Woogie

The lines of this work are no longer only black. Biographical information indicates that the painting was initially exhibited at a show in February 1941, at which time the lines were all black. The artist would then have added the red lines – or perhaps, more probably, painted some of the black lines red – during the autumn of the same year:

New York Boogie Woogie, 1941-42,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 92 x 95,2

Fig. 14 Diagram A shows a horizontal proportion formed by black lines while Fig. 14 Diagram B highlights a vertical area formed by red lines. In Fig. 14 Diagram C, the opposites approach equivalence, which is reached in Fig. 14 Diagram D:

Diagram A

Diagram B

Diagram C

Diagram D

The composition reveals probable equivalences in which one direction or the other shows a slight predominance without either coming to prevail completely and establishing a permanent condition. Everything reverts to the construction and deconstruction of unitary syntheses of the opposing directions, which are simultaneously syntheses of two colors in this case.

The accents of color that the artist must have added in 1942 (above all the small planes in the lower section) do not alter the composition significantly. They add “verticality” in an area that would otherwise be dominated by horizontals but serve above all to enrich the composition with color.

Traveling along the lines, the space opens up and then concentrates in the form of more stable relations that are then challenged again.

Here too, everything changes while something “between the lines” evokes a sense of greater equilibrium.

Summarizing the above

Let us now summarize the evolution of Neoplasticism during the 1930s.

We have seen some works where the square opens up and multiplies all over the canvas:

while other works show a square in progress appearing and disappearing within a dynamic vertical field:

and other works reveal the need to maintain the visibility of a large square:

We shall find these three different types merged in one canvas – New York City (Fig. 15) – Mondrian painted in 1942 when the black lines have become colored.

Let us for a moment see why this one painting can be considered a synthesis of the above mentioned works. In the next page we will examine Fig. 15 in depth.

Fig. 15 Diagram A shows a multiplicity of horizontal and vertical rectangles as well as diversified square proportions (same as this type of compositions).

In Fig. 15 Diagram A a large square area is also noted upwards to the right as found in these type of compositions:

Fig. 15 Diagram B shows how a central square form is developed toward the centre inside a vertical field that runs from the bottom to the top of the canvas (like these type of compositions):

With New York City (Fig. 15) Mondrian will reach a synthesis of all the compositions produced during the 1930s before reaching a marvelous synthesis of his entire oeuvre with Broadway Boogie Woogie and Victory Boogie Woogie Mondrian’s two last paintings which will be examined in the following pages.

Next page: Neoplasticism – Part 5

back to overview

Copyright 1989 – 2024 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More