Please note: If on devices you click on links to images and/or text that do not open if they should, just slightly scroll the screen to re-enable the function. Strange behavior of WordPress.

The beginnings

By naturalism we mean the first phase in which Mondrian still emulates natural semblances. Mondrian painted some three hundred fifty works, nearly a third of his entire output, during his naturalistic phase. I say about three hundred fifty because there is of course no clean break between the naturalistic phase and the subsequent development toward the so-called Expressionistic period. Some of the works produced between 1907 and 1908 can in fact still be described as naturalistic while others are already characterized by a more accentuated use of color.

The works selected here illustrate the variety of subjects from which the young artist drew inspiration, making it possible in some cases to highlight aspects that were to become salient characteristics of his approach during the subsequent phase of development. The works produced between 1893 and 1907 were predominantly still-lives, portraits, and above all landscapes including drawings in pencil or charcoal, watercolors and works in oil on canvas:

Slide the carousel and click on the images to see a full format.

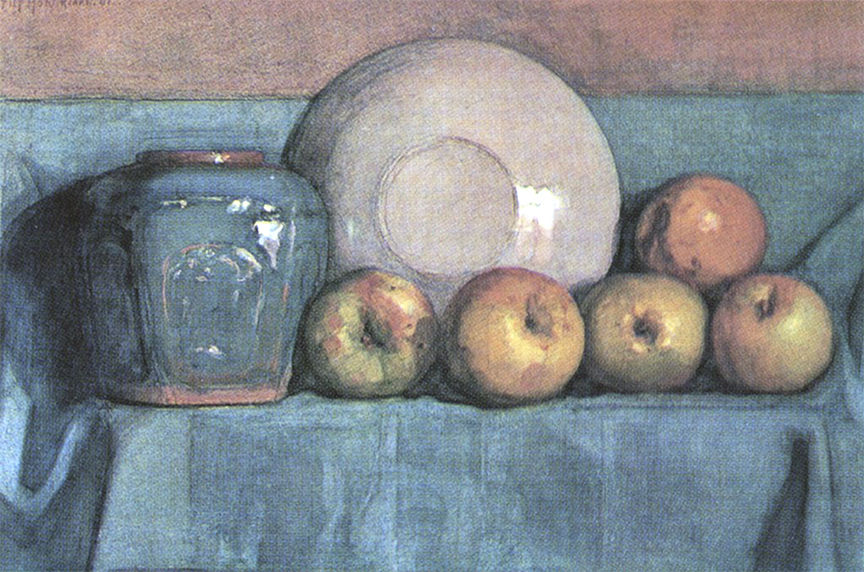

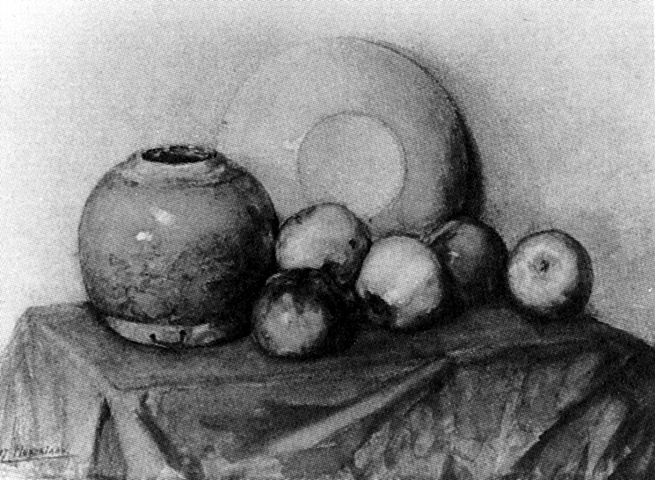

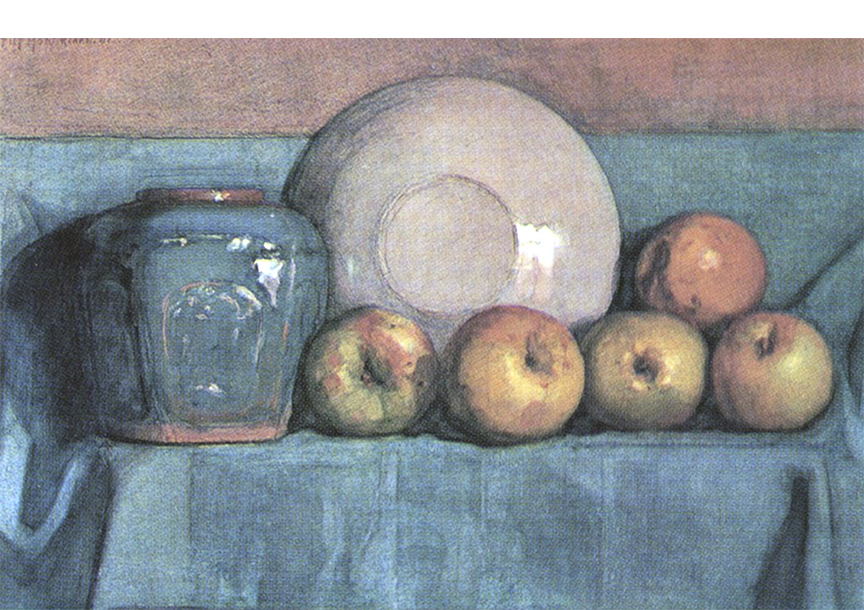

In the still-lives the painter combines human artifacts (plates and vases) with natural products (fruit, fish, and flowers), thus creating attractive contrasts between precise, sharply defined shapes of man-made objects and the random organic natural forms; harmonious alternations of lines, surfaces, and volumes that open and close on interacting to generate finely balanced compositions in terms both of form and of color.

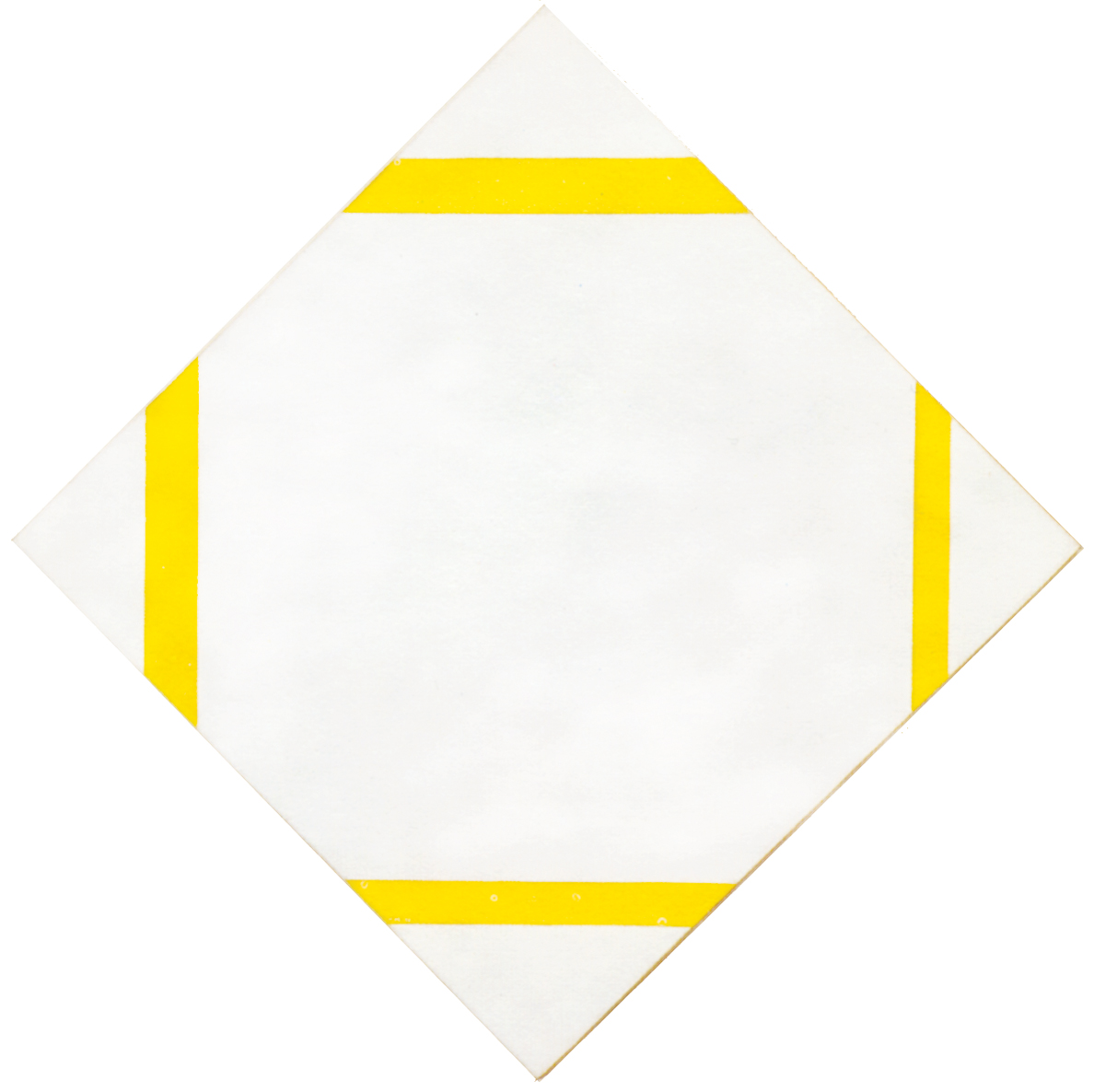

A premonitory still-life

Like Cézanne, Mondrian often went back to the same subject and painted it in different ways. We shall take as an example a series of still-lives highlighting a dialectic between the one and the many; a theme that would become the common thread in Piet Mondrian’s entire oeuvre.

In the first painting we see some apples lying at random on a table. Each apple differs from the others in terms of position and appearance. In the other three paintings we see apples together with a large round plate positioned vertically in such a way as to present a circular shape acting as a background to the apples:

In the two last paintings we note a vase in addition to the plate. The plate is now turned to the wall and its base appears as a circle of similar size to the apples. In the last version the circle is located in the center of the composition:

Watercolor on Paper, cm. 37 x 55

A relation is born between this perfect circle and the imperfect circles of the apples, as though the painter wished to show the changing appearance of natural forms (the apples) and a form of greater constancy and precision (the circle presented by the plate, a man-made, artificial object).

The perfect circle placed in the center evokes an ideal model of the variable and multiform natural appearance.

The landscapes

The landscapes depict rural areas of the Netherlands, showing houses, churches, farms, and scenes of everyday life, woods and rows of trees, moored boats or windmills silhouetted against the horizon.

The artist often painted riverside landscapes:

Watercolor and Gouache on Paper, cm. 46 x 57

The solid and static shape of a house is reflected in the dynamic flowing water of a river suggesting contrast and ideal interpenetration between the human quest for firmness and durability (the house) and the ever-changing becoming of life and nature, in this case of water.

“In art, it is important to distinguish two kinds of balance: 1) static balance 2) dynamic balance. It is always natural for human beings to seek static balance. This balance is obviously necessary for existence in time. But vitality, in the continuous succession in time, always destroys this balance. (Mondrian)

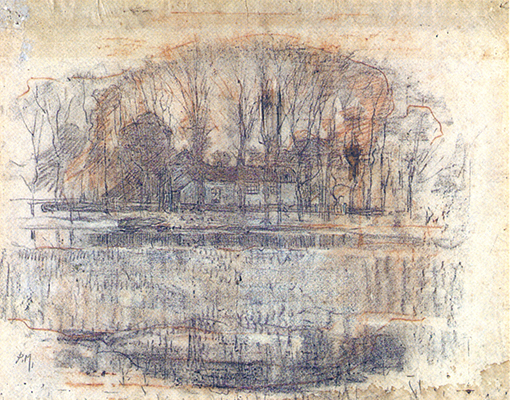

In Geinrust Farm, Compositional Study the arched profile of the trees is reflected in the river to evoke an oval form:

Sanguine and Pastel on Paper, cm. 47,5 x 65

The oval suggests the desire to contain the flowing expansion of the river and consider nature in its wholeness. “I was struck by the vastness of nature and I tried to express expansion, tranquillity, unity”. (Mondrian)

The flowing water of the river expresses an expanding and becoming space while the oval form suggests a tendency toward concentration and unity. The oval remains however open to the sides, that is to say to the boundless space of nature evoked by the river. Any human attempt to comprehend the infinite and mutable space of nature at once (the oval form) would appear pretentious to the artist.

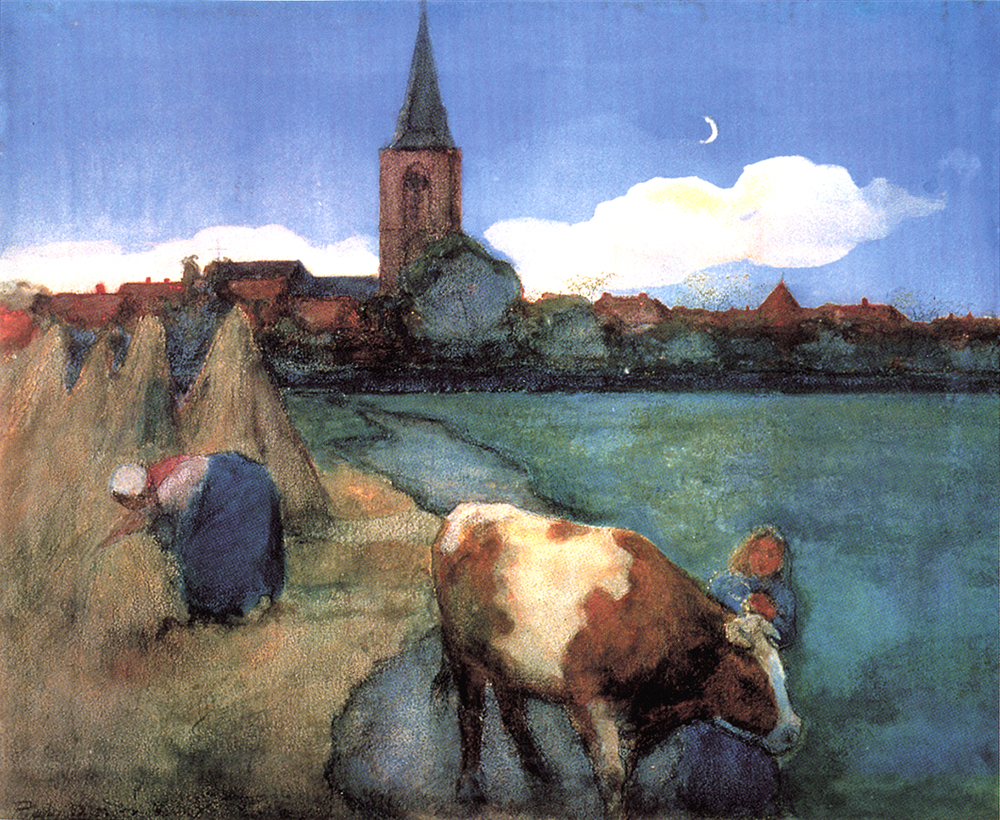

The search for unity is also manifested through the use of light. Around 1907 the artist worked at several paintings in the light of evening and by moonlight:

Oil on Canvas, cm. 71 x 110,5

Unlike sunlight, which accentuates colors by creating contrasting reflections and shadows that increase the manifold appearance of nature, the light emitted by the moon is faint and makes it possible to perceive the broad outline of the landscape; details are reduced and the multiform natural appearance appears more synthetic.

A special landscape

The artist painted many landscapes, sometimes returning to subjects that evidently suggested something very precise to him. The landscape we now examine presents in a different form the theme of the one and the many that we have observed in the still-life examined above.

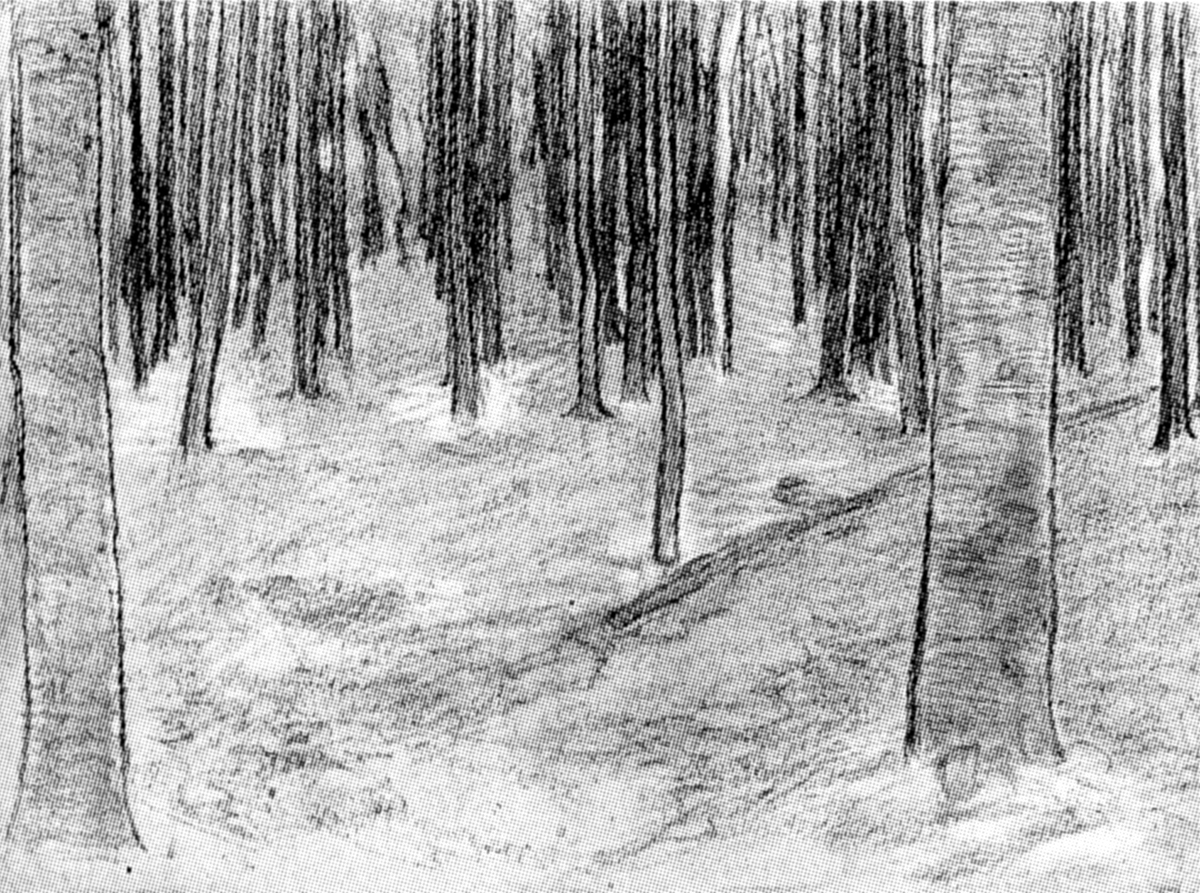

Around 1899 Mondrian paints only the trunks of some beech trees in a wood. Fig. 1 shows a recent photograph of analogous whereabouts which may have inspired the artist. Each trunk has its own particular appearance and, all together, they express the sense of endless variety seen in nature that the painter expresses in a drawing (Fig. 2):

Recent photograph of a wood of beech trees

Wood with Beech Trees, Drawing, c. 1899,

Pencil and White Chalk on Paper, cm. 32 x 40

The ground, from which the vertical logs rise, extends horizontally.

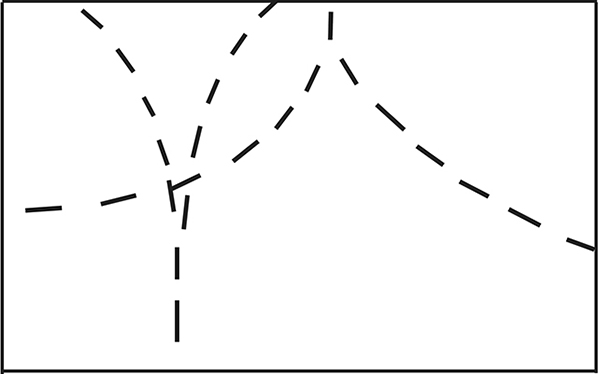

The variety of vertical trunks seen in Fig. 2 concentrates towards the upper central area of the composition (Fig. 3) where the horizontal of the ground and the vertical of the trunks compenetrate to become one.

Wood of Beech Trees, 1899,

Watercolor and Gouache on Paper, cm. 45,5 x 57

Wood of Beech Trees, 1899,

Diagram

A multiplicity of trunks, each one different from the other, merge together into an ideal unity. Again, as in the still life of 1901, the desire to suggest a manifold space that finds unity is manifested in the central area of the painting.

We will see how this tendency to emphasize a synthesis in the center of the composition will be a constant feature until 1920 when the compositions have become completely abstract.

In the paintings of these years, whether still-lives or landscapes, the artist saw nature on the one hand as multiplying its appearances and prompting the consciousness to contemplate an extended, multiform space, and on the other as always remaining the same. Mondrian’s gaze settled on the variety of particular aspects without forgetting that all that variety is ultimately an indissoluble unity.

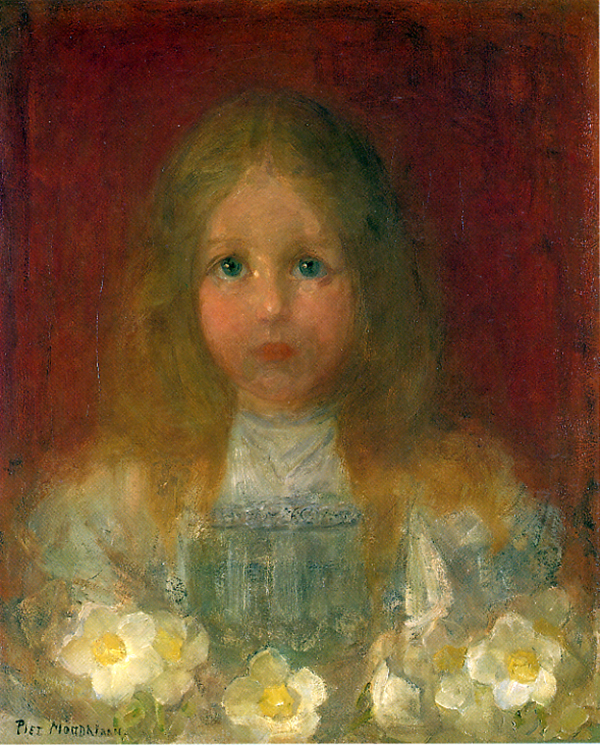

Human figures

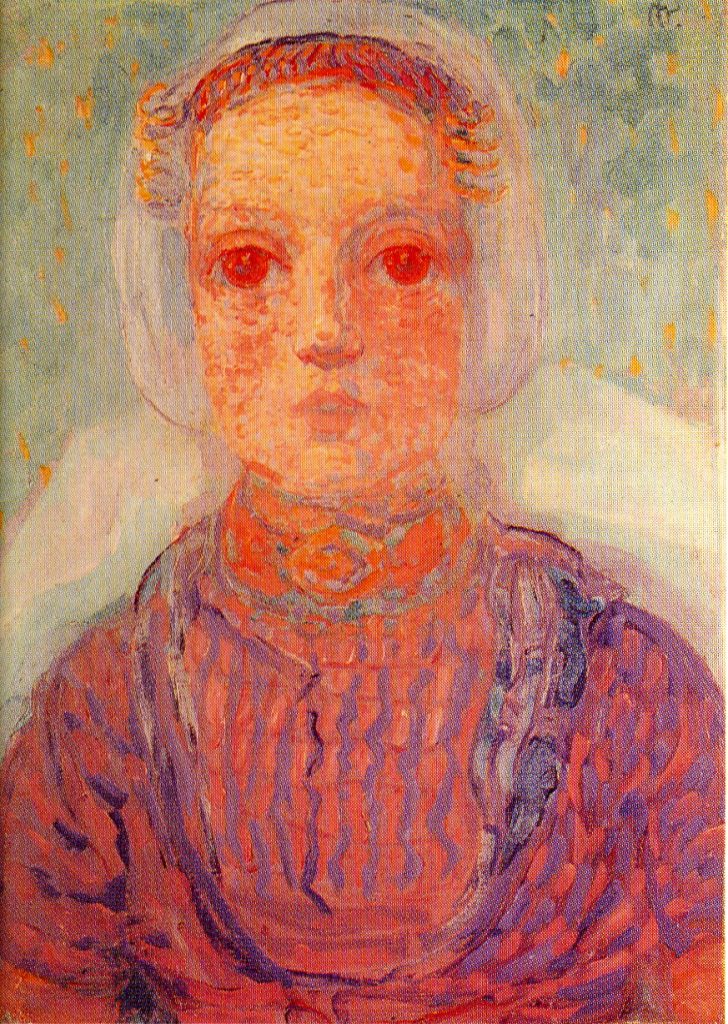

The human figures consist of a variety of characters. Some are portraits produced on commission and others prompted by the painter’s own interests. These are mostly presented in contemplative attitudes. What interested the artist in a face were often the eyes, a link with the soul. He seems intent on capturing some secret, intimate reality in the outward appearance of a face:

Oil on Canvas,

cm. 48 x 63

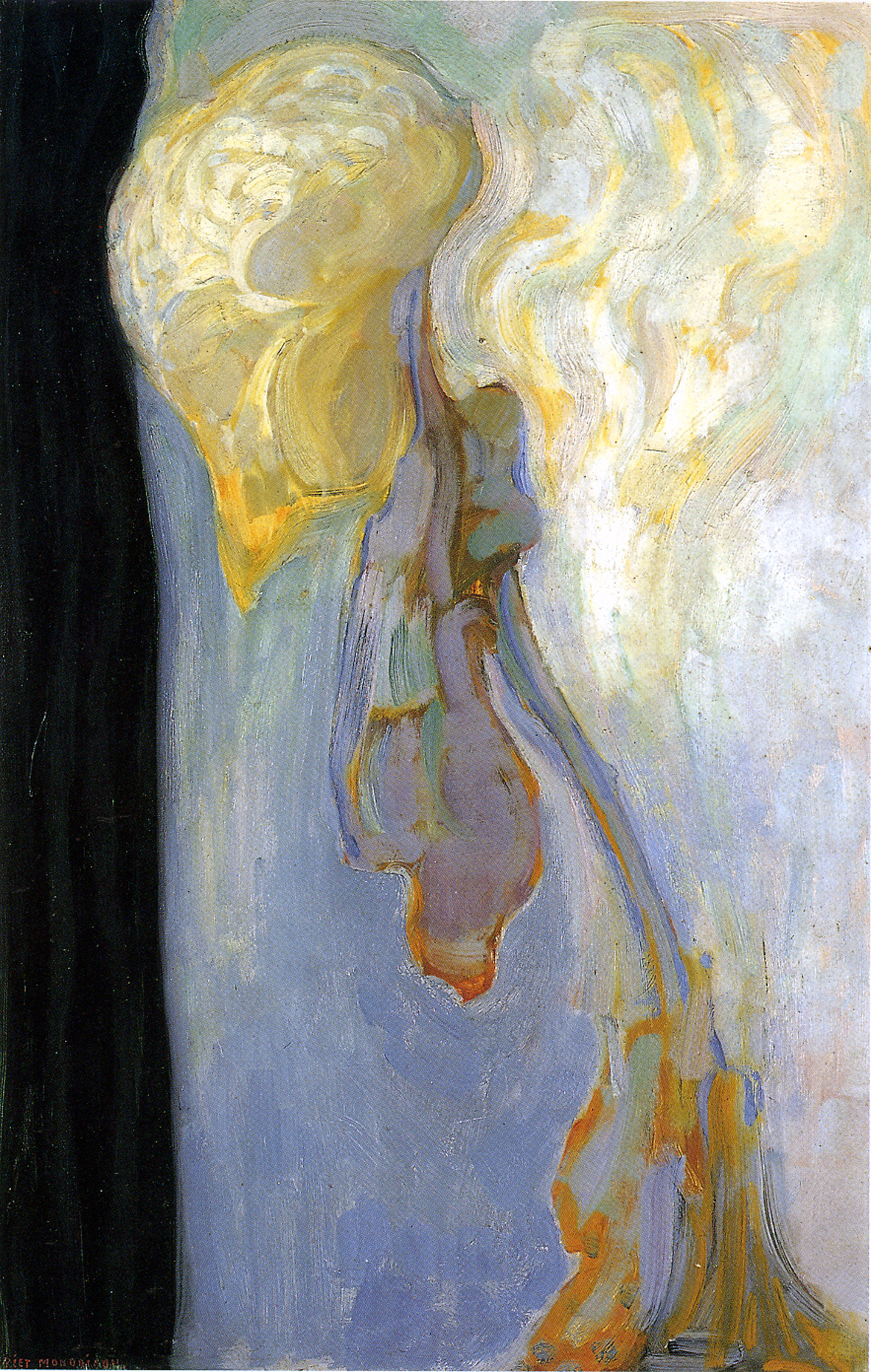

The female figure with one or more flowers is a subject connected with the theosophical theories that interested the artist in that period. The flower indicates a process of inner purification:

The human figures painted by Mondrian are not intent on performing actions of everyday life like those painted by Renoir or Picasso.

Flowers

Mondrian was drawn to the simplicity of a flower while contemplating its complexity at the same time:

Watercolor on Paper, cm. 19,3 x 38,3

While some flowers are painted at the peak of their lifecycle, others are depicted in the phase of their slow, inevitable withering, a process that evokes the cycles of natural life:

Oil on Canvas, cm. 54 x 84,5

Interpenetration of opposites

A theme repeatedly addressed around 1900 is a landscape with a tree standing beside an irrigation ditch, of which Mondrian produced at least eight versions (four oil paintings, three drawings, and one watercolor):

The trunk of the tree expresses a vertical line that displays a tendency to expand horizontally in its upper section, where the branches begin. The ditch instead appears as a vertical that tends to expand horizontally as it moves downward. The vertical trunk opens out horizontally from the bottom toward the top and the ditch does the same thing but in the opposite direction. The two tendencies meet in the central area of the composition to suggest the interpenetration of opposing elements. Here too we see the dawn of the dialectic of opposites that was to inform all of Mondrian’s subsequent work.

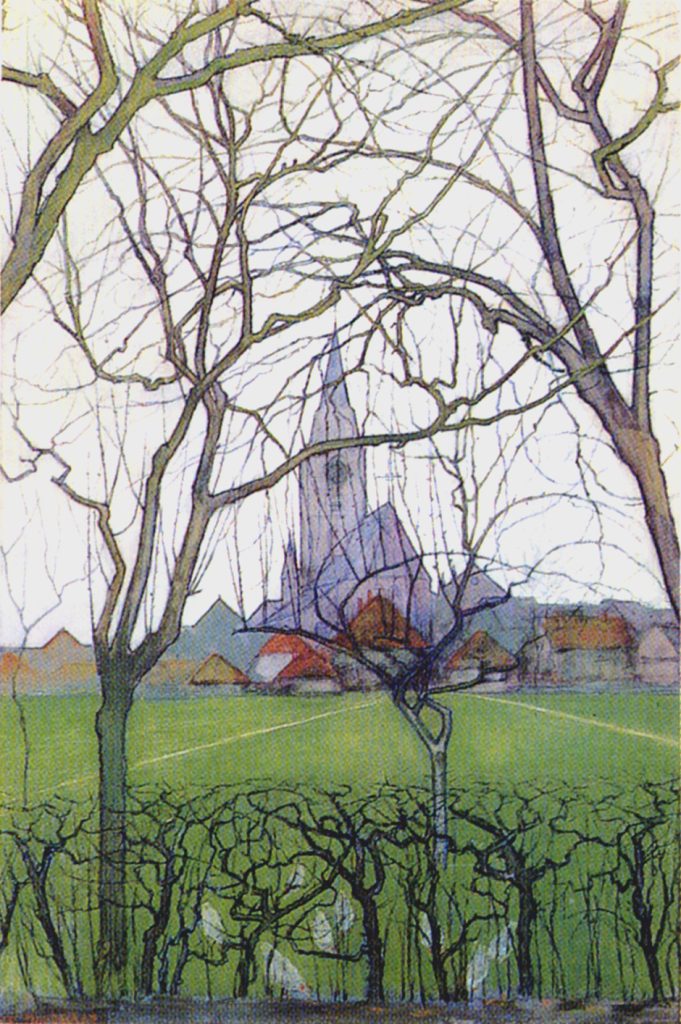

St. Jakob’s Church

Another variation on the same theme is a landscape at the center of which we see a village church. It is the St. Jakob’s Church in the village of Winterswjik where the artist’s family has been living in.

After preliminary studies, the painter represents the scene from a particular viewpoint which allows him to express contrast between the chaotic web of the tree branches and the rectilinear and precise shape of the architectural skyline of the village in the background and particularly of the vertical church tower:

Gouache on Paper, cm. 50 x 75

The branches develop toward all possible directions contrasting one another, whereas the church tower in the center firmly and unequivocally points upward. It seems as if through the contrast between the disordered crowd of branches and the neat architectural skyline the artist wants to evidence on one hand the unpredictable course of natural life and on the other the more neat stability human beings need to carry on their life. A dialectic between the natural and the spiritual.

Same as the branches, the hedgerow at the bottom, with some chickens behind, evoke the unceasing, uncatchable flowing energy of nature.

Oil on Cardboard,

cm. 36 x 36

In 1909 the artist was to paint a tree interpenetrating into a church facade.

The interpenetration of the spiritual and the natural will be a leit-motif of Mondrian’s lifetime work.

next page: Mondrian’s Expressionism

back to overview

Copyright 1989 – 2024 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More