“Art should make visible the invisible” (Paul Klee)

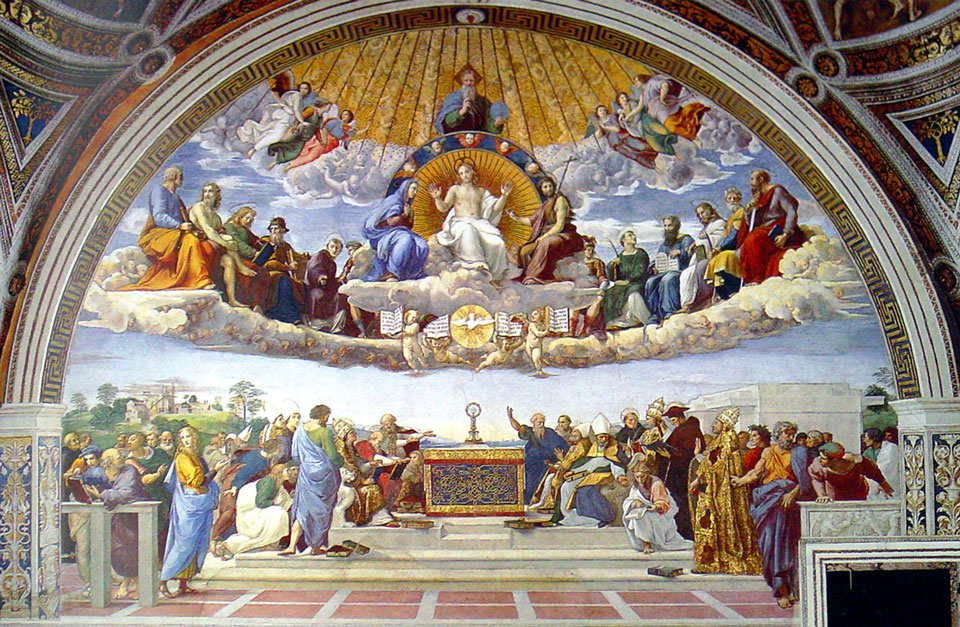

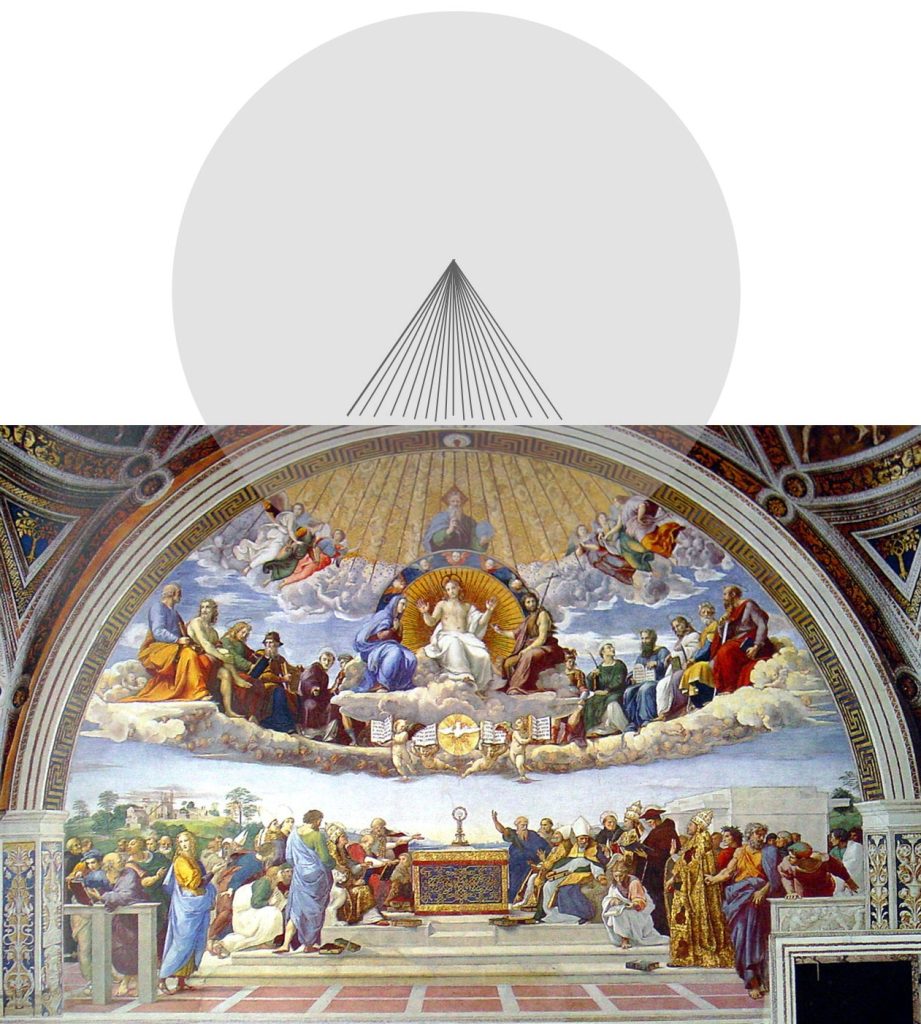

The lower part of La Disputa del Sacramento has the monstrance as its vanishing point. The parallel lines of the floor and the whole scenario of human figures converge towards that point. The middle area (saints and prophets) does not seem to have any vanishing point but has as its center the circle of the Holy Spirit that concentrates in itself the semicircle of clouds on which the twelve figures of saints and prophets sit.

While the semicircle opens up revealing the twelve figures, the Holy Spirit closes in synthesis to reiterate that saints and prophets draw inspiration from that center together with the contiguous four books of the Gospels. While the semicircle of clouds opens to the diversity of holy men, the round of the Holy Spirit concentrates them into one and the same “thing”.

A circular process consisting of straight lines

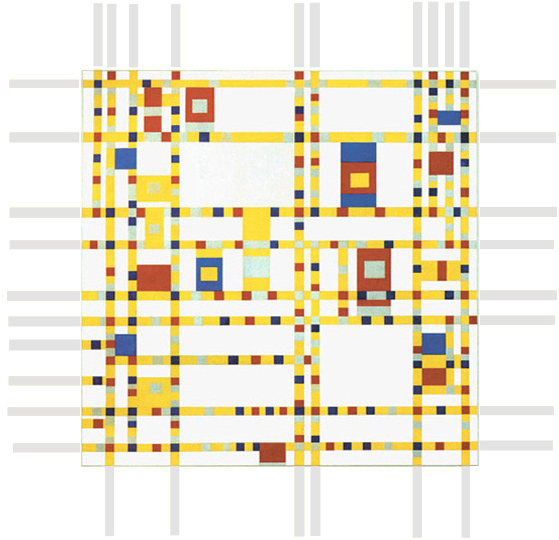

In Broadway Boogie Woogie multiplicity turns into unity and then the one opens up and becomes multiple again.

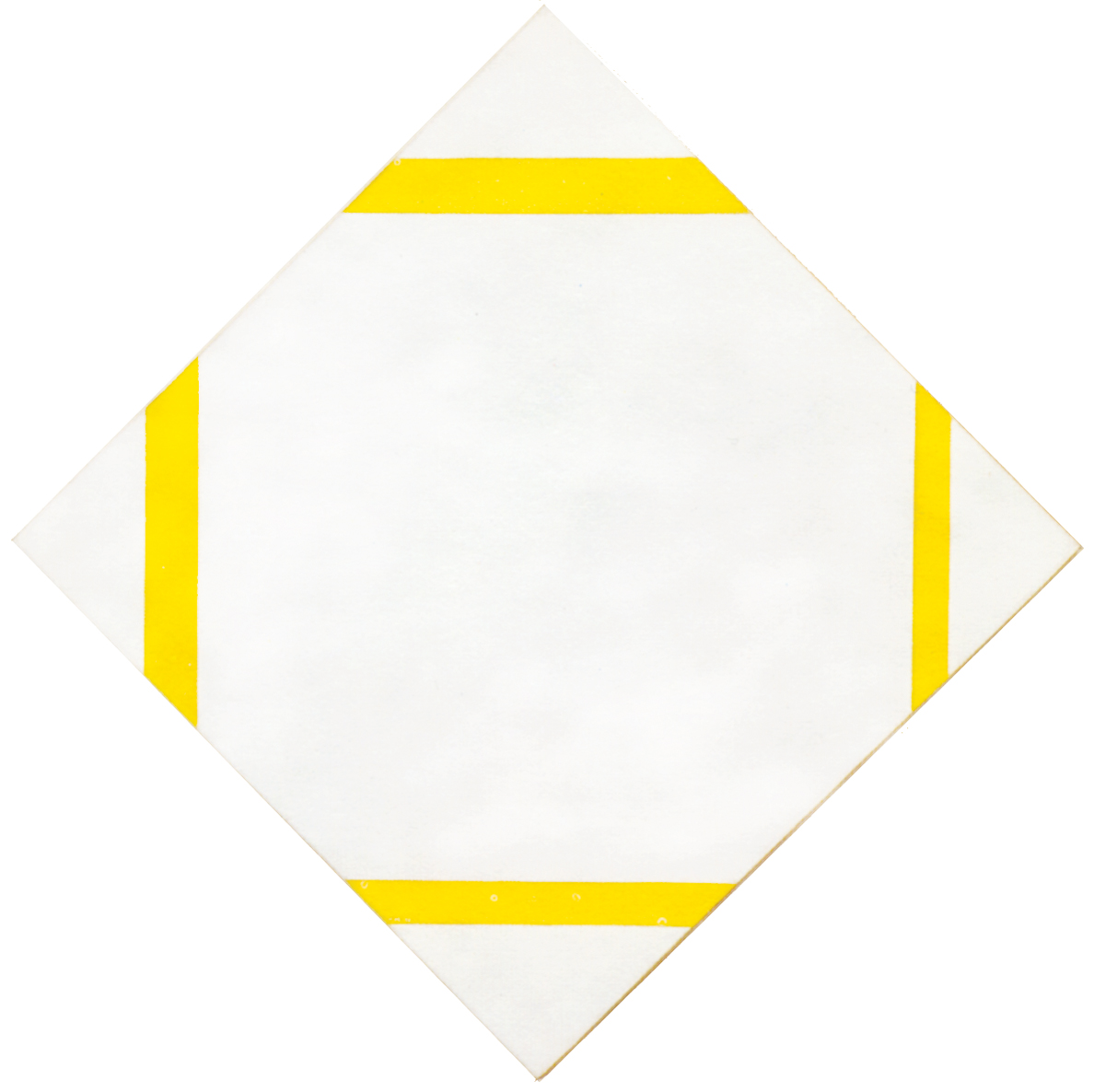

A process in which the end coincides with a new beginning evokes circularity. A circularity that, however, is expressed with straight lines. A circularity so wide as to appear rectilinear; like the horizon of a sea that appears to us as a continuous straight line but is in fact round.

It takes a long time (an infinite time like the extension of a straight line) Mondrian seems to say, before we can contemplate the circularity that unites all things.

The round is often used to express the idea of a synthetical whole, but the circular shapes we can paint on a canvas will never be omni-comprehensive of the processes of real life. In painting, straight lines keep the space open while curved lines tend to tighten and close the space within itself. The Dutch painter uses straight lines, i.e., a symbol of extended and open space that seems to invite us to open our minds; to avoid closing ourselves immediately into descriptions, definitions and judgments that would inevitably leave out much of what is real.

The geometry of Broadway Boogie Woogie exhorts us to contemplate the infinite variety of reality without, however, renouncing partial and temporary syntheses (multiplicity turns into unity which then reopens to multiplicity).

In daily life this is certainly very difficult. How much fear it arouses in the human soul to be open to variety and to confront diversity. Every closure, every form of intolerance and racism is born out of fear.

Different visions of one God

With a figure of God in human likeness, Raffaello satisfied his clients but, with a point outside the image that unifies the whole fresco (see above Diagram E) the artist suggests that their idea of God was not yet necessarily fully exhaustive of God. Five centuries later, Piet Mondrian confirms that what we call God is our own idea of the one inscrutable God.

“God is not Catholic. – Pope Francesco told me in one of our meetings. – It is ecumenical, it is one God that each religion reads through its own Holy Scriptures, knowing, however, that God is unique, has no name, has no figure.” (So writes Eugenio Scalfari of one of his dialogues with Pope Francesco).

Because the unity Mondrian evokes is expressed in abstract form, it can represent different ideas of the very unique God.

Is God just an idea?

We should always remember that one thing is the objective, inscrutable God and another thing is our idea of God. As Immanuel Kant said, we can only know our representation of things and not the things themselves. Could changing our idea of God mean changing God? And what kind of God would be a God who depends on man’s ideas? To equate mankind’s thought with God who should be immutable, would in the final analysis mean to sclerose thought.

That is why, perhaps, certain religious doctrines struggle so much to adapt their ideas to the changed reality of new times and are so reluctant to revise and update the way in which they interpret the divine.

Zen

Can an idea of God that changes over time be true? Zen spirituality teaches us not to get stuck on ideas. This is why I personally prefer to imagine God in abstract form. Certainly ideas and words have their great value in paying homage to the divine. Following the threads of thought, words evoke, tell, describe and we humans often need the warmth of a tale. However, the more we think and attempt to describe God, the further away we get from God.

I think of the legend of the Tower of Babel: the more men raised their tower to get closer to God, the more God created disorder through different languages that made each other unintelligible. The more men tried to reach and conquer the one, the more it opened up to the many; same as the unity in Broadway Boogie Woogie does.

A lonely and tiring path

Is it therefore the words and ideas of men that distance us from God? In fact where the importance of words is emphasized, spirituality often becomes an oppressive moral rule. Here, perhaps is one of the crucial points: can mankind’s spirituality be reduced to a set of moral laws? The path that leads to God in a form free from dogmas, rituals and pre-packaged and often obsolete images has always been and still is a lonely and tiring path.

it is also true that especially in the past, but still today, religions have had to use the divine in a moralistic sense to help regulate social life.

Nevertheless and with all due respect for certain institutions that are centuries old, I believe that making a moralistic use of God today is an abuse, an abuse and an exploitation of God. Every life situation would need special consideration. There are no certain rules that can be valid always, in any case and for everyone. This means relieving spirituality of the burden of a moral doctrine. It is however true that rules must always apply, and so the question arises as a relationship between what can change and what must remain, between the dynamic and the static, between the particular and the universal.

To pretend that a certain idea of God is true always and in any case, means putting mankind and his ideas above everything else and, therefore, above God as well. Men still confuse the true God with their idea of God. Mankind still confuse the subjective with the objective. Thus it happens that human beings still make war on each other when two different ideas of God diverge.

When we speak in the name of God, we need a lot of humility and respect for other ideas of God that are worth as much as ours because all of them are only subjective representations of a probable but not verifiable objective entity. There is no way to establish when a certain idea of God comes close to the presumed objective reality, but there is a certain criterion to understand when it moves away from it and this happens every time a certain idea of God tries in every way to impose itself on the others. The distance from God becomes unbridgeable when, to this end, violence is used.

An endless source of variety

In Broadway Boogie Woogie a certain configuration of unity changes and opens up to new possible configurations. The form (our ideas) changes but not the substance, i.e. the vital universal energy that is expressed by the relationship between opposite lines and the most vivid colors such as yellow, red and blue.

A secret and unreachable energy that generates us, our bodies, our emotions and our ideas. Ideas that, precisely because they change, are kept alive and current and therefore suitable to put us back in tune with the inscrutable “designs” of the objective entity that may be eternal and unchanging but, as far as we can see on this planet, is also above all an inexhaustible source of changing variety.

Yellow, red and blue are for Mondrian a symbol of variety. An image in which such heterogeneous parts achieve a dynamic equivalence makes one think of the question of diversity in which none of the components claims to impose itself on the others. In Broadway Boogie Woogie the three primary colors interpenetrate and become a single entity while maintaining each of their specific characteristics. Each part contributes with its own particular nature to the balance of the whole. I think of the words of Pope Giovanni Paolo II when he said “the roots of each are not erased in universality.”

No flattening of diversity

Globalization cannot mean flattening of diversity. In Broadway Boogie Woogie a true unity is given in the synthesis and equivalence of all the components and not in the overpowering of one over the others. The dynamic process we have observed in the painting finds a moment of pause only when all the components reach equilibrium in the unitary plane. The world will not find peace as long as one prevails over the others, precluding balance, harmony and unity. Paradise on earth?

Today it is necessary to think complexity with the parameter of equivalence and no longer of symmetry or equality. In a universe that is believed to be symmetrical, the condition for an equivalence of two different things is their equality, i.e. the negation of diversity. Two different things will never be symmetrical or equal but they can acquire the same value, that is to say, they can be equivalent.

The space of Broadway Boogie Woogie is not symmetrical and yet each thing, although different in shape and/or color, is as valuable as the other. This is one of the secrets of neoplastic geometry that, in my opinion, will be of great help in the search for new possible social and spiritual models.

back to past and present

Copyright 1989 – 2025 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More