Please note: If on devices you click on links to images and/or text that do not open if they should, just slightly scroll the screen to re-enable the function. Strange behavior of WordPress.

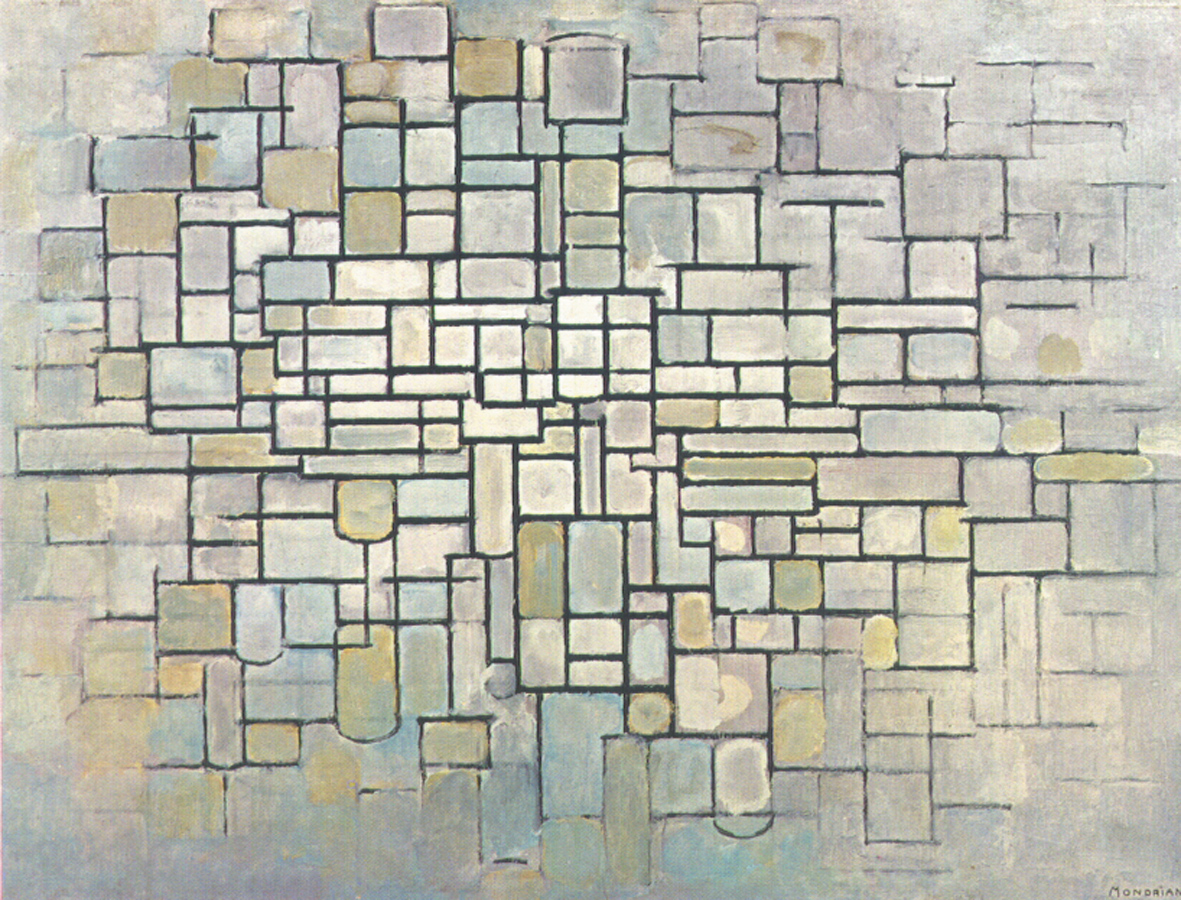

An exhibition of International Modern Art opened in October 1911 at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. It featured twenty-eight works by Cézanne, some Cubist paintings by Braque and Picasso, and works by various other artists. Called upon to assist in organizing the exhibition, Mondrian was to be strongly influenced by the Cubist works.

What was Cubism?

The work of Braque and Picasso is usually regarded as marking the birth of Cubism. In actual fact, however, the Cubist revolution had already begun with Cézanne’s last canvases. What was Cubism? The term was invented by an art critic who used the term “cubist” to describe a painting by Georges Braque presenting a landscape as a group of juxtaposed volumes, which the critic interpreted as cubes. This obviously does not explain the true meaning of Cubism.

A static picture

Painting had previously been based on a conception of space grounded on linear perspective, a system of visual representation developed in Italy between the end of the 14th century and the first half of the 15th. Perspective space assumes a constant relationship between an immobile observer and a series of objects or a landscape, again more or less immobile. Movement at that time was basically geared to the walking pace of human beings, at which speed the world appears to be practically motionless.

The societies of that era changed far more slowly than today also in social, economic, and political terms. People at the beginning of the 15th century needed to believe that the universe was measurable, governed by symmetry, and centered on mankind. The vanishing point of Renaissance perspective is nothing other than the projection onto the painted surface of the fixed position from which mankind believed itself able to observe and know the universe. The whole of the visible world converges on that single point.

A dynamic viewpoint

Reality altered drastically toward the end of the 19th century, above all in the cities, where electrical lighting and the new means of transport and communication changed ways of life and introduced previously unknown forms of acceleration. The progress ushered in by technology changed social, economic, and political relations radically transforming mankind’s relationship with the world.

Philosophy, science, and above all the new rhythms of urban life born in the wake of ever-increasing speed worked at the beginning of the 20th century to undermine the foundations of some certainties, one of which was pictorial space based on linear perspective.

The new rhythms of life accelerated the relations between the observer and the scene observed, especially in the cities. As a result of increasing speed, visible reality tended to become an ephemeral sequence of views running into one another; a landscape, a building or a tree appeared in a quick succession of different viewpoints.

Albert Einstein posited the inseparable linkage of space and time in 1905. The fourth dimension (time) is connected with space in the first Cubist works by Braque and Picasso, where an object appears on the canvas in all the forms it takes when observed from a moving position: the strange faces with three, four or five eyes, the single bottle that seems to multiply beneath the gaze of an observer moving around it. Unlike naturalistic painting, Cubism is a way of seeing and representing the world from a dynamic viewpoint.

A new plastic space

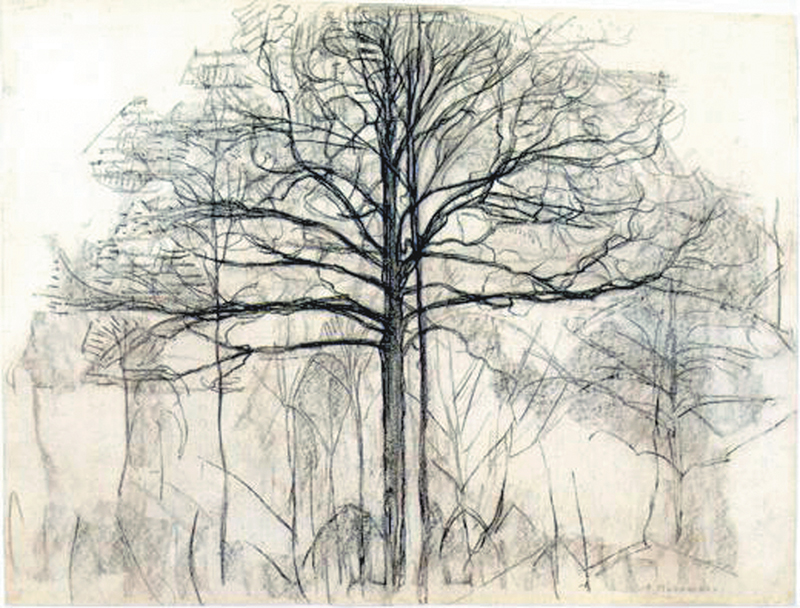

Mondrian was to regard Cubism also and above all as a way of giving concrete shape to his intimate vision of reality. How long is the duration of a tree, a building or a landscape when observed from a moving position? What characterizes and unifies within the observer’s consciousness all the forms that suddenly appear and disappear a moment later? All this was very clear to Mondrian long before he took up Cubism. He had seen the “landscape” since 1908 as a relationship between exterior and interior.

With the dunes, the buildings, and the tree, he constructed space as a relationship between subject and object. Intent on finding balance between the ever-changing appearances of the world (a horizontal boundless expansion) and a sense of synthesis and duration invoked by awareness (a vertical concentration), he was already on the path toward a process of abstraction. The new Cubist perspective, which involves the subject in its changing relations with the object, prompted developments opening up the way to new formal solutions.

Mondrian’s Cubism

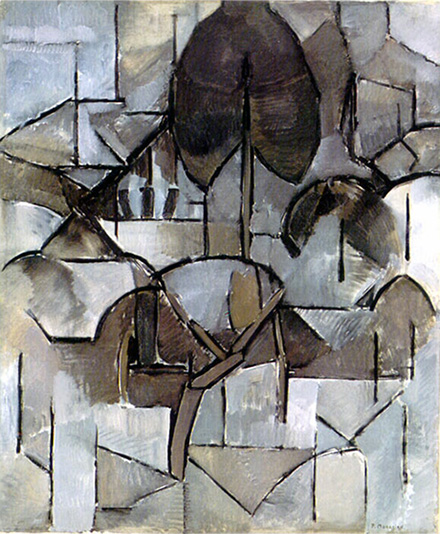

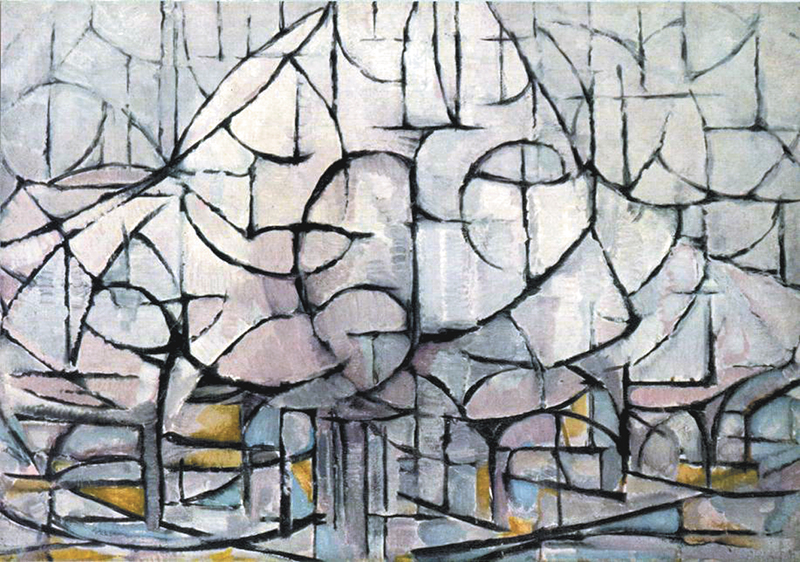

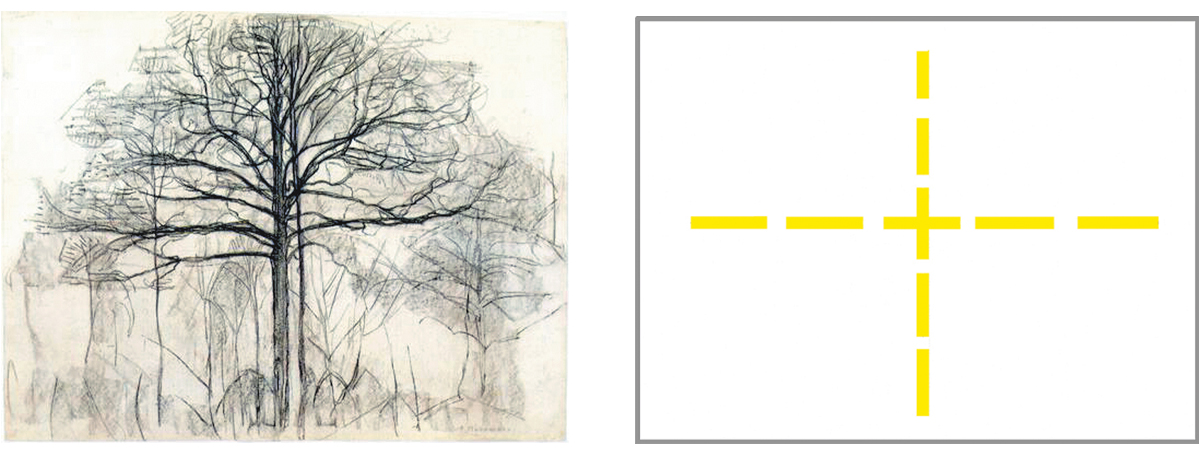

By the end of 1911 Mondrian decided to move to Paris. While getting to grips with the new urban environment, the artist continued for some time to work on the tree motif. Between 1911 and 1913 the tree acted as a guiding thread while naturalistic space was opened up to the new stimuli of Cubism transforming the recognizable aspect of a tree into an abstract composition:

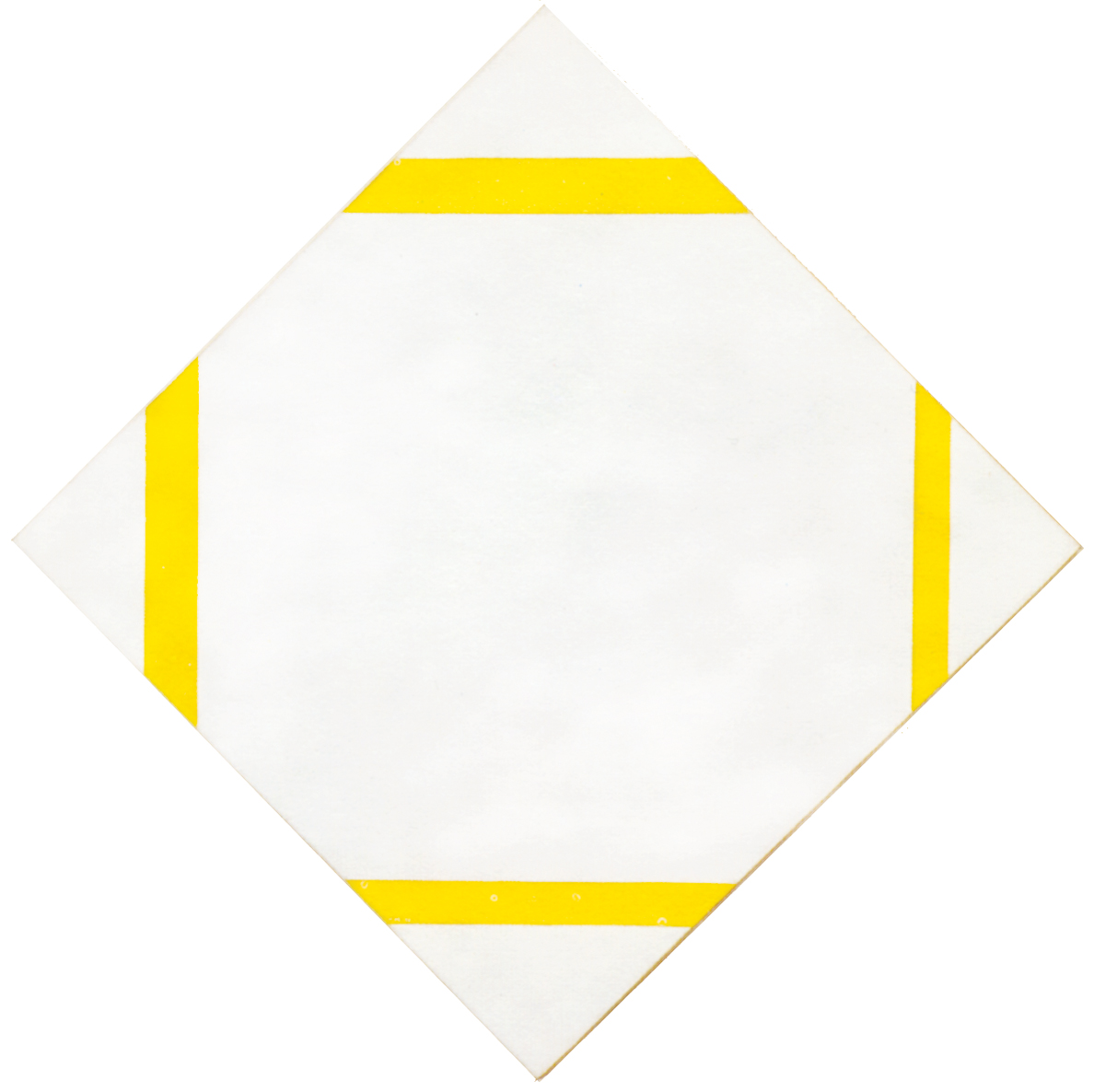

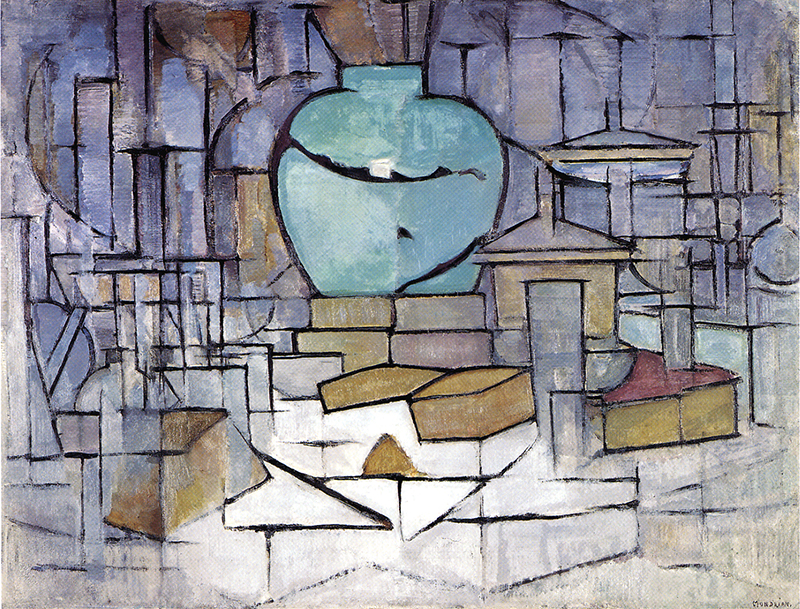

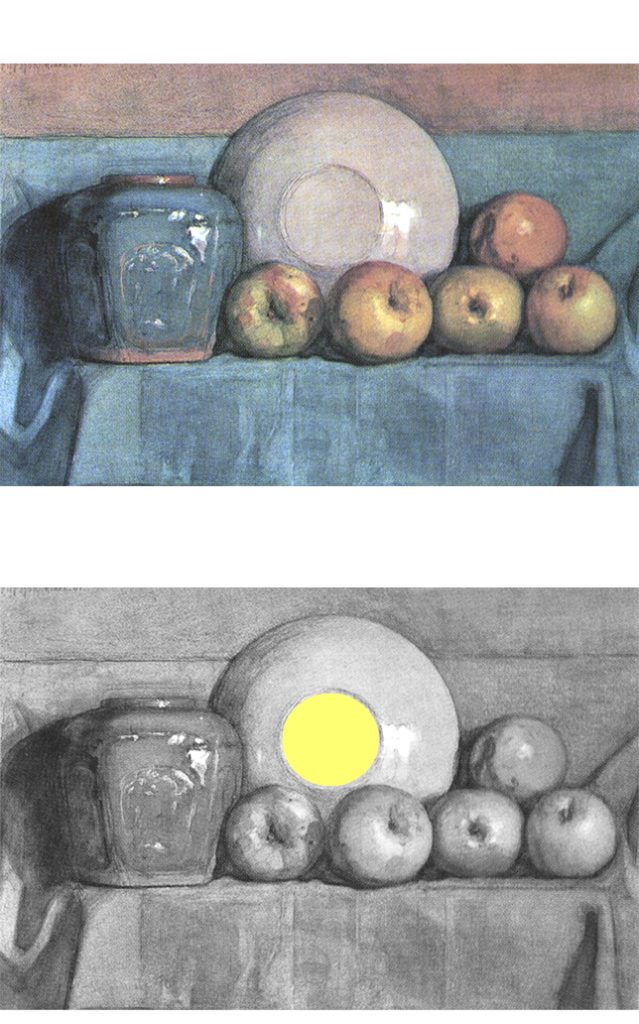

While the tree was the central motif in the transition toward Cubist space, there was no lack in this period of canvases addressing other themes, e.g. a still life with ginger pot, which Mondrian painted in two versions, the first in 1911 and the second in 1912:

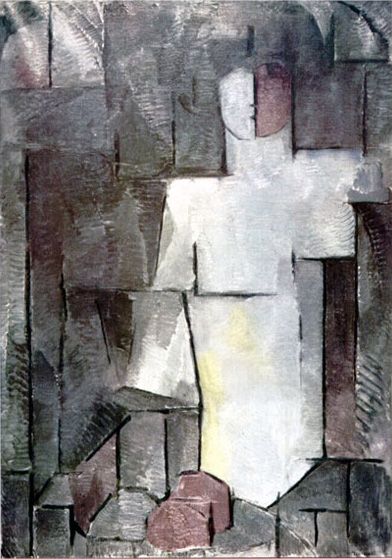

Stylized human figures and landscapes were also featured:

Unity of cubist space

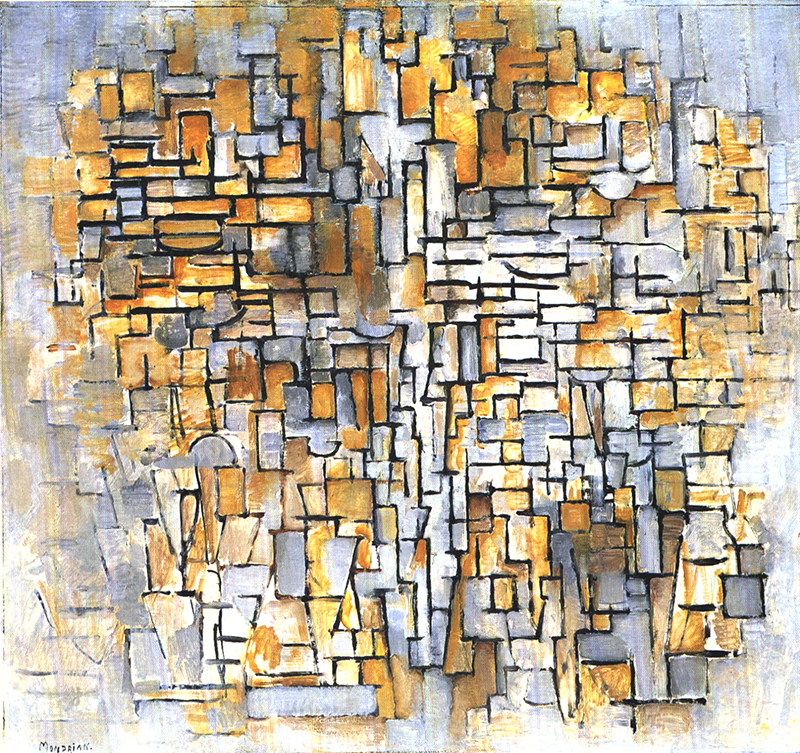

Objects seen from the Cubist viewpoint expand and become one with space:

Solid and void interpenetrate to become a single connected structure. The naturalistic (or figurative) space modeled on the more static and certain appearance of things now began to adapt to the changing form that things assume while interacting with one another beneath the gaze of a mobile observer.

In the previous page we have interpreted the trunk of the naturalistic or expressionistic tree as a unifying moment with respect to the manifold space expressed with the branches. The Cubist transformation of the tree puts now an end to this: object and space interpenetrate and thus remove the unifying function of the trunk, which dissolves and tends to become one with the many branches.

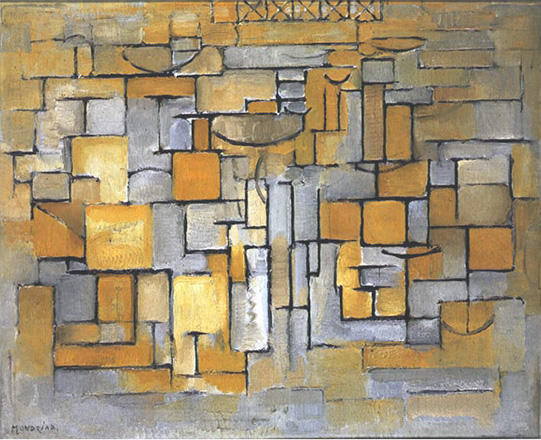

While this happens, space can be seen to thicken toward the center in some canvases. This can be seen in Fig. 1 with two semicircles in the central area that appear designed to evoke a synthesis of the composition, and in Fig. 2 with the light blue jar, again placed in the center. Two different motifs but a similar structure emphasizing a synthesis in the central area:

With the dissolution of the trunk and while the definite form of objects is gradually lost, cubist space is soon transformed into a sea of fragments and the painter seeks compositional cohesion and synthesis.

He endeavors to anchor the parts, which now float freely in space in the absence of the unifying profile of the objects. During this phase Mondrian seems to be looking for a mainstay or fulcrum (Fig. 1 and 2).

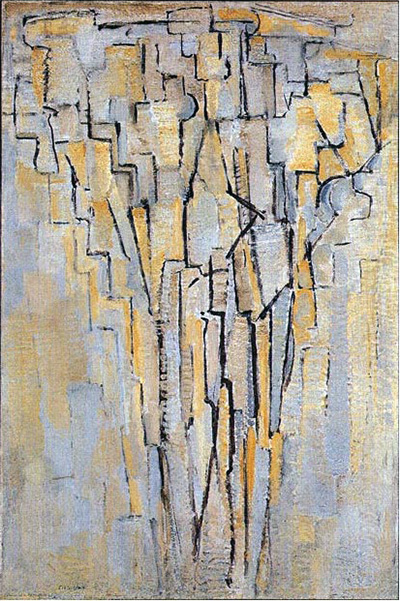

In the lower part of Fig. 3 we again see an absolute vertical (like the buildings of the previous years) that displays a tendency to expand horizontally in the upper section:

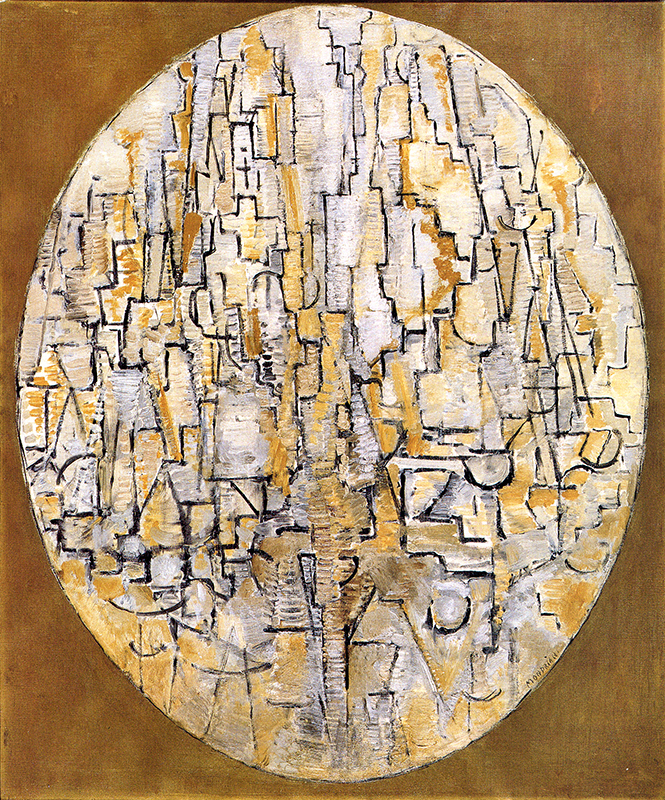

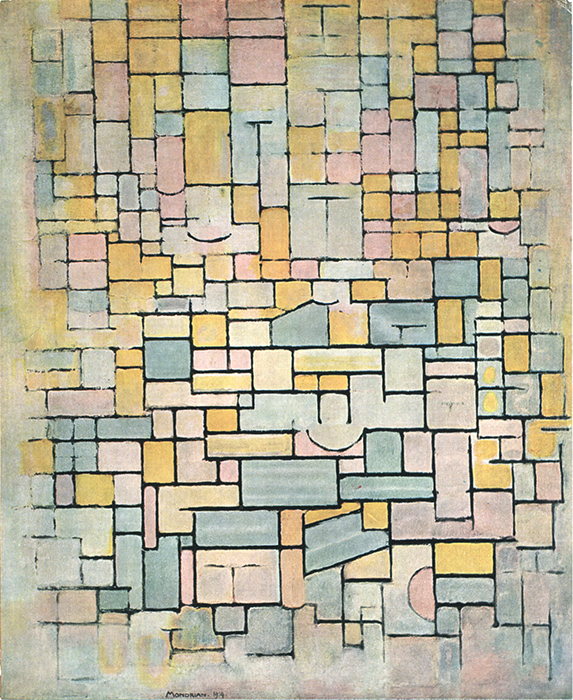

Something similar but developed in the opposite sense can be seen in Fig. 4. The composition is in fact generally horizontal in its development like the land and seascapes of previous years:

A reading from below toward the central area of the image gives the impression of the bottom of the canvas converging in a triangular shape on a central point highlighted by a small vertical segment. A predominantly horizontal tendency is then reasserted.

While horizontal and vertical interpenetrate in the other Cubist canvases in a multitude of small, juxtaposed signs that disintegrate space, the painter appears to have endeavored in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 to maintain compositional coherence based on one predominant direction. In one case (Fig. 3), a vertical undergoes slight horizontal expansion; in the other (Fig. 4), the horizontal suggests a vertical that avoids manifesting itself too clearly so as not to disrupt the composition as a whole. The spatial development alternates between horizontal and vertical and almost suggests a desire to return to the compositional space of the dunes and buildings of 1909-10.

Mondrian appears for a moment to opt once again for the more absolute predominance of one direction or the other in an attempt to endow the fragmented Cubist space with a certain degree of synthesis and unity.

An oval shape

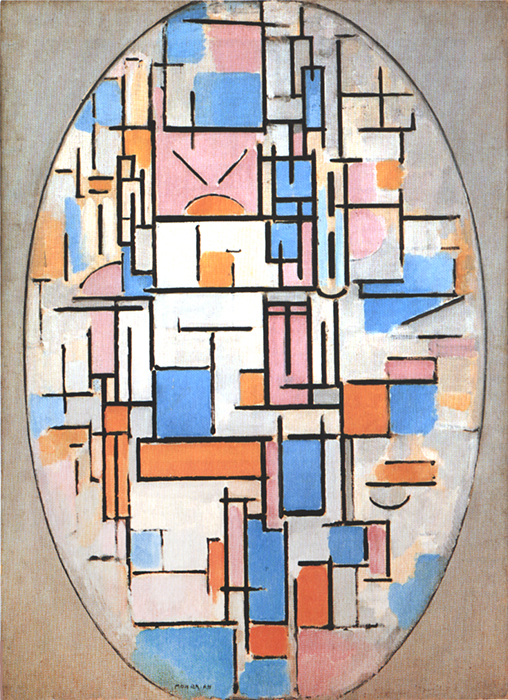

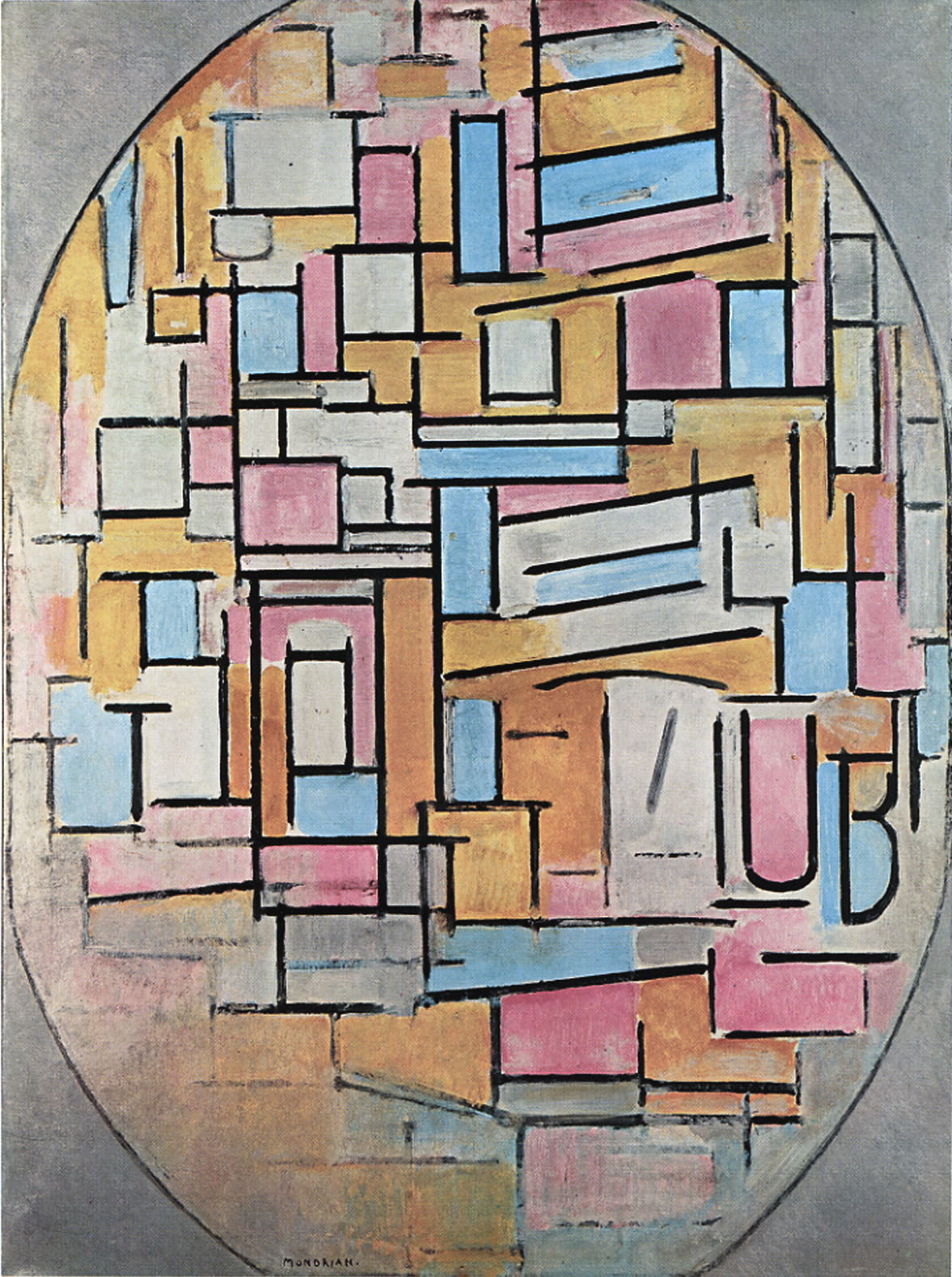

In his attempts to endow Cubist space with greater synthesis and unity one year later Mondrian introduces an oval form (Fig. 5):

Braque and Picasso also used the oval in some works of Analytical Cubism.

Mondrian had already suggested an oval outline as early as 1906 in some landscapes and some depictions of dunes.

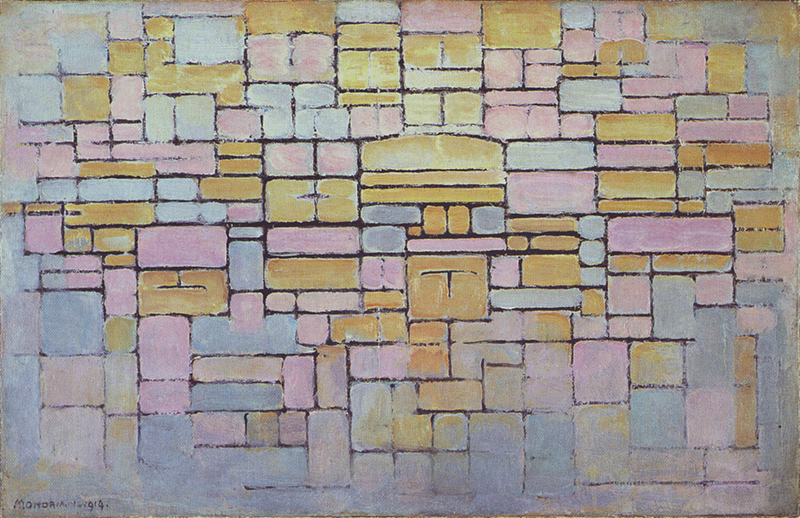

Reducing color contrasts

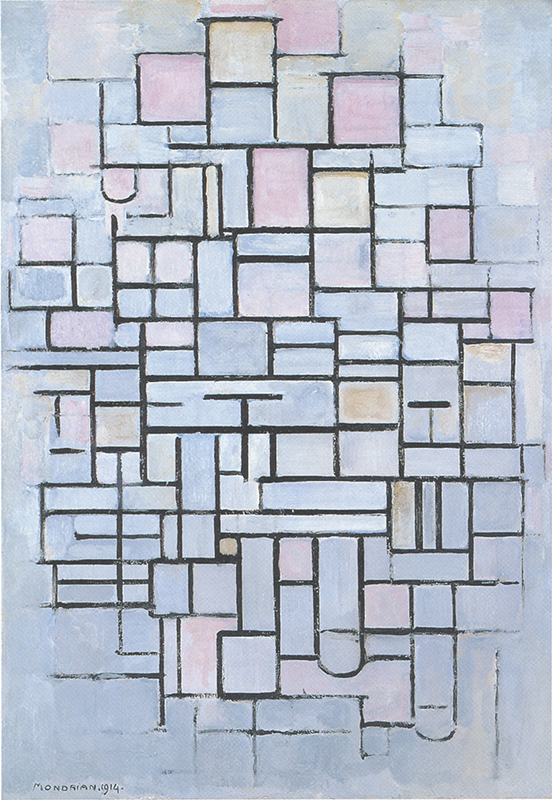

While the artist was to adopt the oval in many canvases of 1913, 1914 and 1915, this was not the sole means employed in his search for synthesis. He also chose in this phase to reduce the chromatic range in order to maintain greater compositional unity, at least in terms of color. The strong contrasts are attenuated and the bright yellows, magentas, blues, and greens used in previous works give way to tonal variations of ocher, brown and gray, as can be seen in Fig. 6, 7 and 8:

Approaching linearity

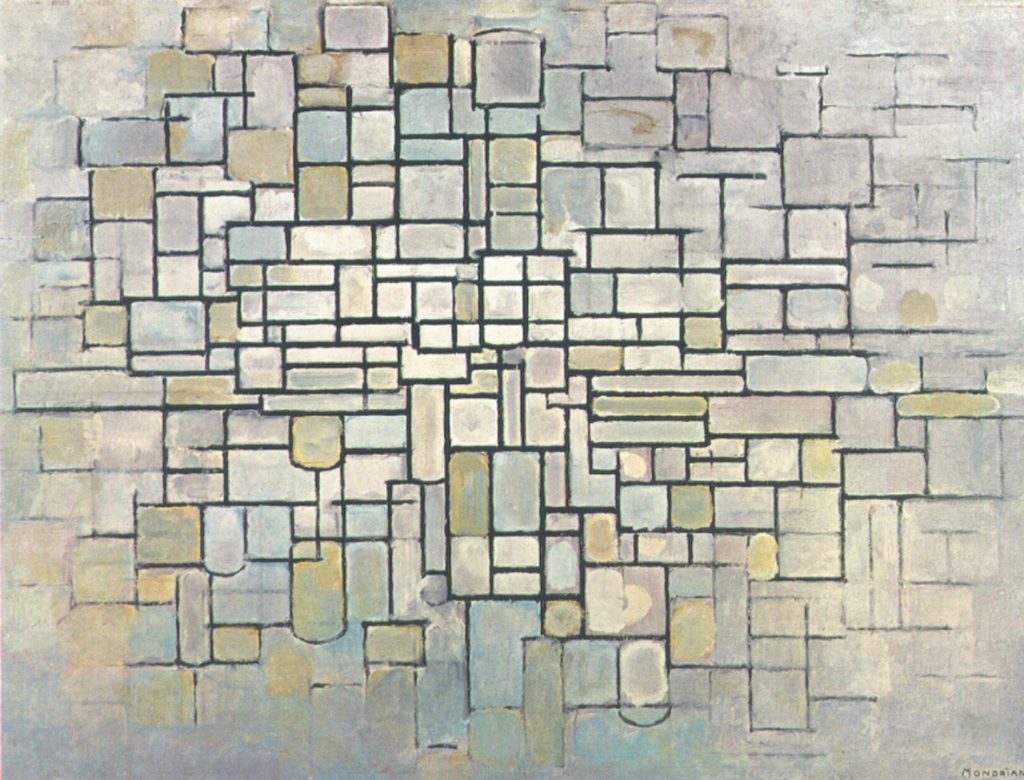

While using an oval and reducing the chromatic range, Mondrian worked to uniform the complex tissue of signs. Still curved, oblique, horizontal, and vertical (Fig. 7 and 8) the signs will reach a more homogeneous alternation of horizontal and vertical lines (Fig. 9). The formal structure of the compositions thus attains greater clarity:

While the oval unquestionably helps to endow the composition as a whole with a sense of unity, it does not appear to form part of the multitude, of which it is intended as a synthesis. It appears to be too absolute and detached from the multiplicity of signs within it. It evokes unity but not exactly the unity that the painter wishes to see manifesting itself on the canvas.

Objective and subjective unity

Mondrian is intent on expressing a unity that generates itself from within the composition and is not, like the oval, applied from the outside. If we translate this into existential terms, we realize that the idea of unity he so cherished is something of an everyday nature depending on the human subject in its relationship with surrounding reality. Unity for Mondrian is not something absolute, a priori, outside the world.

Synthesis and unity are questions posed by the human being with respect to the immensity of nature. Mankind and its consciousness can, however, only operate inside the natural universe, as any desire to stand outside it would inevitably entail falling into a surrealistic metaphysical condition. The unified external synthesis expressed with the oval appears to be this, and Mondrian could hardly feel satisfied with it.

The oval thus appears (Fig. 5), is expressed in more discreet form suggesting a desire to interpenetrate with manifold space (Fig. 7):

and disappears almost entirely (Fig. 10) before reappearing (Fig. 11).

The oval form appears now faintly (Fig. 12) and then once again in a more sharply defined form (Fig. 13):

The oval is expressed in some cases with a bold black outline while in other works, the signs fade away toward the edges of the canvas generating an oval shape that can be glimpsed but with no visible outline as such. The oval appears to become more tenuous when the colors are more subdued (Fig. 10 and Fig. 12) and more clearly expressed when the colors once again become bolder so as to accentuate the contrasts and thus the manifold aspect of the composition (Fig. 11 and Fig. 13).

Form and color are connected. When the range of chromatic variation is reduced, everything is bathed in the “same light” and the eye perceives a greater sense of cohesion between the parts, in which case the oval can therefore be toned down. When the colors emphasize the individual parts, the oval instead encloses them firmly to recall that all this contrasting variety is still a unified whole. Mondrian is involved in a difficult game of balance between form and color, being concerned in this phase to make the structure more unified while at the same time avoiding any undue sacrifice of color.

The oval appears in one case to have been applied from the outside in order to enclose all the variety within it (Fig. 5 and 11):

and in another to be intent on springing from the internal space itself, which fades away toward the edges to suggest an oval (Fig. 10 and 14):

I believe that this is a way of evoking the desire for unity to be generated from inside the composition.

Reaching unity from within

As mentioned, still curved, oblique, horizontal, and vertical the heterogeneous variety of signs gradually gives way to a more homogeneous alternation of horizontal and vertical lines in other canvases:

The composition thus gains greater breath and clarity.

By reducing reality to a multitude of orthogonal signs, Mondrian performs an arbitrary operation with respect to everything we see. This enables him, however, to express a great variety on the canvas (every sign differs from the others in terms of the greater or lesser predominance of one direction or the other) while at the same time maintaining something more constant (the perpendicular ratio).

Every sign differs from the others but they all share the same intimate nature (the perpendicular relationship), just as every human being, every animal or tree is unique and unrepeatable but all express some fundamental features that make it possible to discern an invisible overall design.

“There is a common design to all things, plants, trees, animals, humans and it is with this design that we should be in consonance” (Henri Matisse)

The “landscape” on which the abstract vision is concentrated overlooks the peculiar aspect of each individual thing so as to focus on what different things have in common.

As Mondrian was to put it, “Art must express the universal”.

While space multiplies in a plurality of different entities, suggesting in abstract terms the manifold aspect of the real world, a common denominator (the perpendicular ratio) now underpins all that diversity, and this satisfies the human mind. Opening up the consciousness to contemplation of the immense variety of the world while at the same time maintaining something more constant capable of holding together as much as possible the multiplication imparted by external reality; opening up to the world without getting lost.

A common structure of things

A fixed point or a mainstay is essential if you are to contemplate diversity and becoming: Cézanne found this in the stereotypes of the cone, the sphere, and the cylinder; Mondrian was to find it in the perpendicular relationship.

Expressing the broadest diversity through variations of one and the same thing means in fact finding the one in the many.

Mondrian’s Cubist space thus builds a bridge between the multifarious natural universe and the unifying consciousness.

I am thinking now of the works of 1909-10 in which we can see a pointillistic structure that already appears designed to suggest a sort of common denominator: the buildings and the dunes.

Mondrian regarded Cubist space not as the interpenetration of objects in motion (as it was for other Cubist and Futurist painters) but rather as the representation of a common, intimate structure of things.

This leads us to reflect about reality in terms of macro and microcosm which will be discussed on a following page.

A new concept of space

Mondrian ascribed to the horizontal the value of everything that can be defined as the “natural” not only in the sense of the natural landscape before our eyes but also as anything that within ourselves in the course of our lives constantly changes always taking on new aspects. In the vertical the artist instead saw a symbol of the “spiritual” that is, of the all-human propensity to seek stability, constancy, unity.

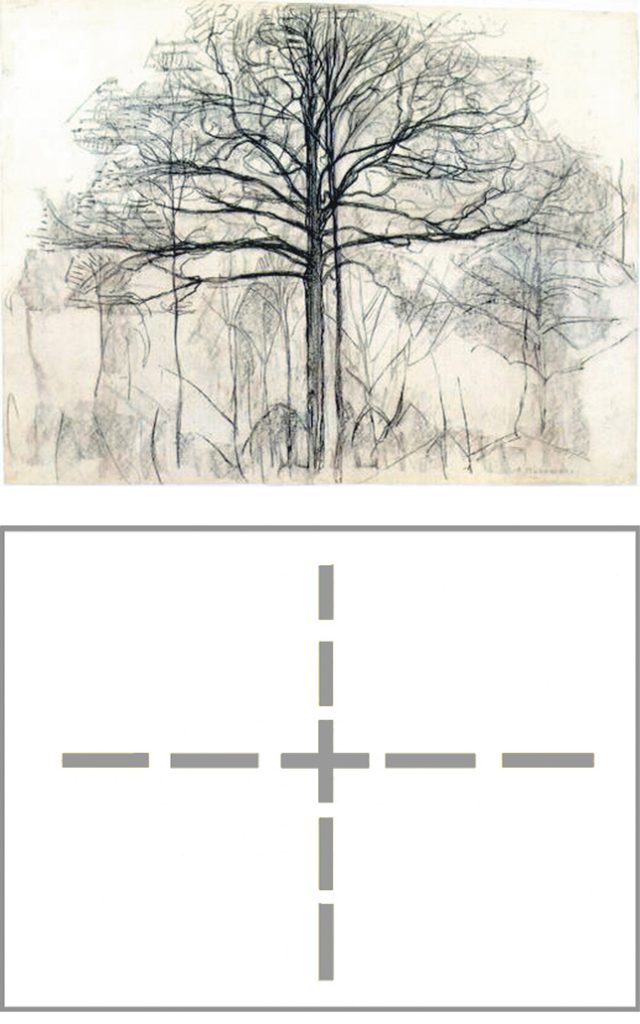

I have interpreted the figure of a bare tree in terms of a relationship between unity (the vertical trunk) and multiplicity (the set of branches) where the trunk holds back and unifies the disordered horizontal expansion of the branches:

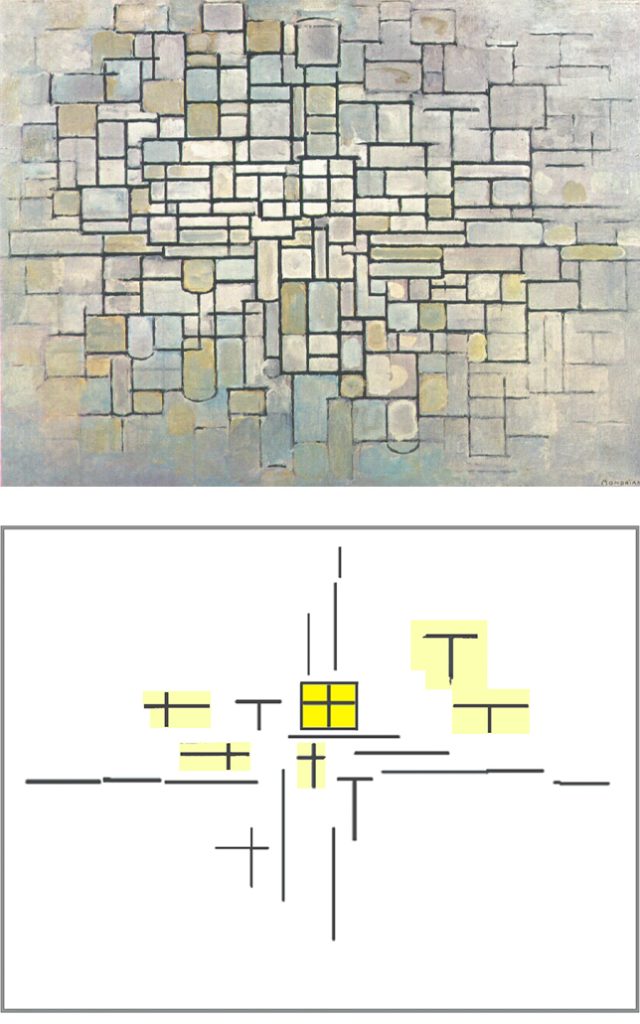

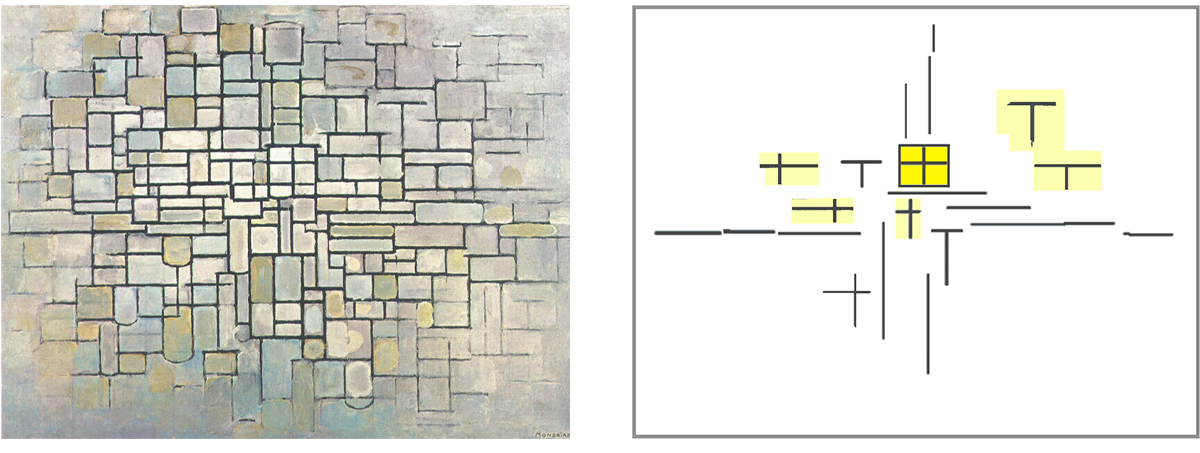

The vertical-horizontal relationship, that is, the basic structure of the tree re-appears now in the center of an abstract composition (Fig. 9) where a variety of horizontal and vertical dashes presents in clearer form the crowded space previously expressed with the branches:

Ever-changing relationship

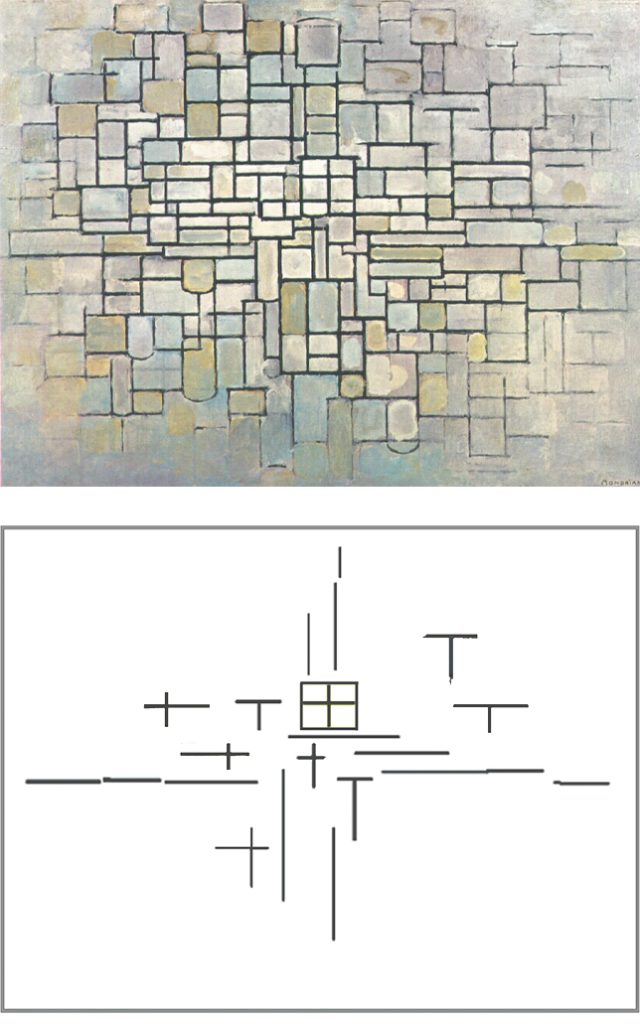

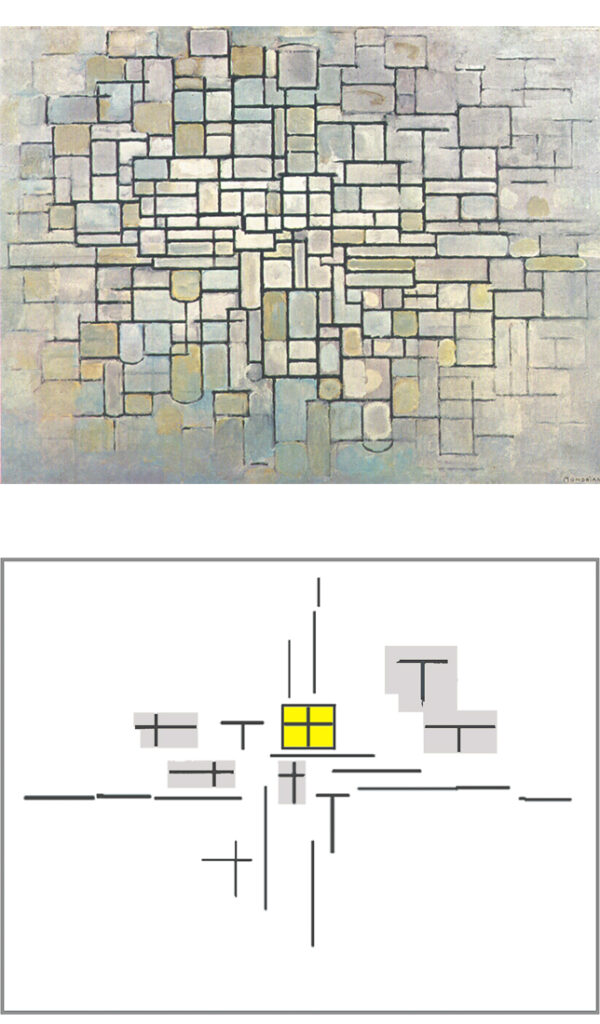

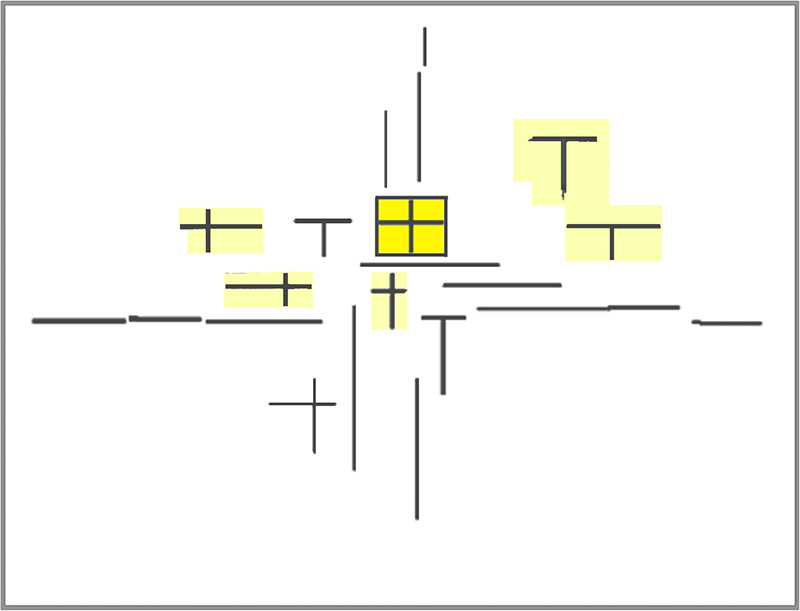

The relationship between opposites (the basic structure of the tree), which is suggested in a rather univocal and static way in Study of Trees 1 (1912), multiplies and takes on ever changing combinations in Composition II (1913):

Composition II, 1913 with Diagram

In the naturalist rendering of a tree the image is limited to the outer form of a specific tree as it appears from a fixed point of observation. In the abstract composition the point of observation becomes dynamic to suggest that a tree can take different shapes depending on the position from which it is observed.

Fig. 9 suggests a dynamic relationship between an observer and one single tree constantly changing in appearance or, at the same time, can convey the idea of different types of “trees”. A rather static space (Study of Trees 1) becomes dynamic (Fig. 9) and this was actually what Cubism was about.

An invisible overall design

Fig. 9: The linear strokes intersect, combine with one another, and separate once again in a constant alternation of the predominance of one direction or the other. Everything is different but can always be traced back to a single intimate reality constantly changing in appearance:

Is nature not an intimate reality, made up of the same basic elements combined in ever-changing ways?

The intersecting of the linear strokes produces areas (marked in gray) that contain signs which appear to isolate themselves in an internal space so as to express something more lasting. While all the other signs are closely interconnected and constantly slide into one another (thus proving almost impossible to pin down), these signs express a certain level of independence from the whole context they are part of. The same thing is observed in some following works:

One of these signs appears in the center of Fig. 9, shifted slightly upward and contained inside a rectangular area:

Unlike the situation observed for the other signs, the opposite directions attain a more stable equilibrium in this central rectangle.

The rectangle appears as a sort of model in which a perfect equilibrium is attained, while all the other signs suggest circumstances that approach that ideal balance to differing degrees and thereby evoke, albeit in abstract terms, the manifold space of the world and the ever-changing situations of life in all their becoming. That rectangle evokes a perfect balance between the stability and unity invoked by the spiritual (the vertical for Mondrian) and the mutable multiplicity manifested by the natural (the horizontal).

Same substantial meaning

Everything changed in Mondrian’s painting through the naturalistic, expressionistic and cubist phases, or rather there was a change in the plastic means serving to give clear shape to a vision of the world that can already be glimpsed implicitly in some early works of the naturalistic phase.

We have seen an example of this in a still-life of 1901:

In the still-life we see a vase and a plate whose base forms a circle of similar size to the apples; the circle is located in the center of the composition. Each apple differs from the others in terms of position and appearance.

A relation is born between the perfect and stable circle of the plate and the imperfect and different circles of the apples, as though the painter wished to show the changing appearance of natural forms (the apples) and a form of greater constancy and precision (the circle presented by the plate, a man-made, artificial object). I have explained this still-life as a visual metaphor of the relationship between the natural and the spiritual.

Round vs. straight lines

Unity expressed by a circle (the plate in the center) is replaced by a unity expressed by a relationship between horizontal and vertical (the central rectangle). “The round, compact line that does not plastically express any relationship was replaced by the straight line in the duality of the orthogonal position which expresses the purest relationship.” (Mondrian)

Figurative and abstract

Both works combine the manifold appearance of the world (the apples in 1901 and the various orthogonal signs in 1913) with a unified synthesis (the perfect circle of the plate in 1901 and the central rectangle with the best possible balance of opposites in 1913).

With a gap of twelve years between them and differing completely in form, the two paintings say the same thing: physical reality multiplies its appearances (the apples in 1901 and the various orthogonal signs in 1913) while the consciousness strives to draw everything back toward an ideal model of greater synthesis (the perfect circle of the plate in 1901 and the central rectangle with the best possible balance of horizontal and vertical in 1913).

The expression of all this in the naturalistic or figurative painting is veiled by the contingent appearance of a certain vase, that particular plate, and those apples. It is precisely through abstraction from the particular appearance of just few things that the Cubist painting suggests a potential broader spectrum of reality.

An abstract landscape

After the naturalistic and expressionistic phase in which the painter pursued the changing appearances of the world with one landscape after another, he now appears intent on finding a “universal landscape” born out of the relationship between the changing appearances of external reality and the demand for synthesis and greater duration invoked by the world within.

Paul Cézanne

“To paint is not to slavishly copy the object, it is to grasp the harmony among numerous relationships and transfer them into a system of one’s own, developing them according to a new and original logic.” (Cézanne)

The task of faithfully reproducing the fleeting appearance of things had been taken over in the meantime by photography and motion picture.

Outer and inner nature

A tendency toward unity is the product of consciousness (Mondrian would say the spiritual) confronting with a manifold and ever-changing nature. It is worth re-calling that nature means here not only the outer world but, at the same time, the inner nature of mankind. How to express reality as a dynamic interaction between the outer and the inner nature except by abstracting from the mere appearances of the outer world?

Religion, philosophy, science

Religions invoke a supreme unity; philosophies elaborate ideas that try to make sense of the controversial human existence; scientists work to translate the complexities of natural phenomena into synthetic formulas. The relationship between the many and the one constitutes a recurrent issue in human beings life.

Natural vitality

All this having been said, Composition II is a painting and therefore subject to the criteria we usually adopt when contemplating a work of art. It is only by seeing this work in original (Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands) that you can appreciate all its beauty, which I am quite incapable of describing in words. Every point of the composition pulsates with energy and everything appears to be connected, just as when we observe a natural landscape and see every patch of green melding and mingling with its neighbor in a succession of light and dark, of boldly defined and more subdued features. The abstract painting is like a concentrate of natural vitality distilled into spiritual energy.

Nature and life still remain the primary source of inspiration for abstract art. The ten thousand different lines and colors that we see around us prove on closer examination to be a single “line”, because in nature everything appears different, manifold, infinite, and is at the same time one. The immensity of earthly nature is one bluish-white spot in the infinite space of the macrocosm and the apparent simplicity of a flower is a small universe.

This same conception of reality will guide the artist in the elaboration of all subsequent abstract compositions until the last two canvases, which will constitute a marvelous synthesis of his entire oeuvre.

next page: Mondrian’s revolution

back to overview

Copyright 1989 – 2025 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More